By Austin Williams, 33rd VA Co. H

The following article was published in the August 1, 2025 issue of the “Living History Gazette.” Read the entire issue here.

A key milestone in any living historian’s journey towards improved authenticity is the moment he realizes the “paper ladies” he’s been carrying in his cartridge box bear no resemblance to period ammunition and commits himself to do better. Unfortunately, like with so much else, the diverse array of small arms cartridges used by the Confederacy forces the dedicated living historian to ensure he has selected an appropriate cartridge for his impression.

Early in the war, dozens of locations across the South hurriedly fabricated cartridges. As the Confederate Ordnance Department became better established and Federal advances forced abandonment of peripheral locations, manufacture of cartridges largely consolidated by mid-1862 at Richmond, Charleston, Augusta, Macon, Atlanta, and Selma, supplemented by smaller or temporary facilities.1

A March 1863 circular designated specific arsenals as the primary source of ordnance for designated forces, assisting the living historian in determining which arsenal most likely provided his ammunition. The Army of Northern Virginia drew from Richmond; coastal forces from Fayetteville, Charleston, Macon, and Columbus; the Army of Tennessee from Atlanta, forces in Alabama from Selma, and forces in Mississippi from an arsenal then active at Jackson. These are only broad guidelines, however, as cartridges were shipped between arsenals as needed. In 1863, Richmond received cartridges manufactured at Charleston and Augusta. The collection at the National Museum of the United States Army includes a cartridge box recovered at Gettysburg containing ammunition from Baton Rouge, an arsenal on the opposite side of the Confederacy that was captured over a year before.2

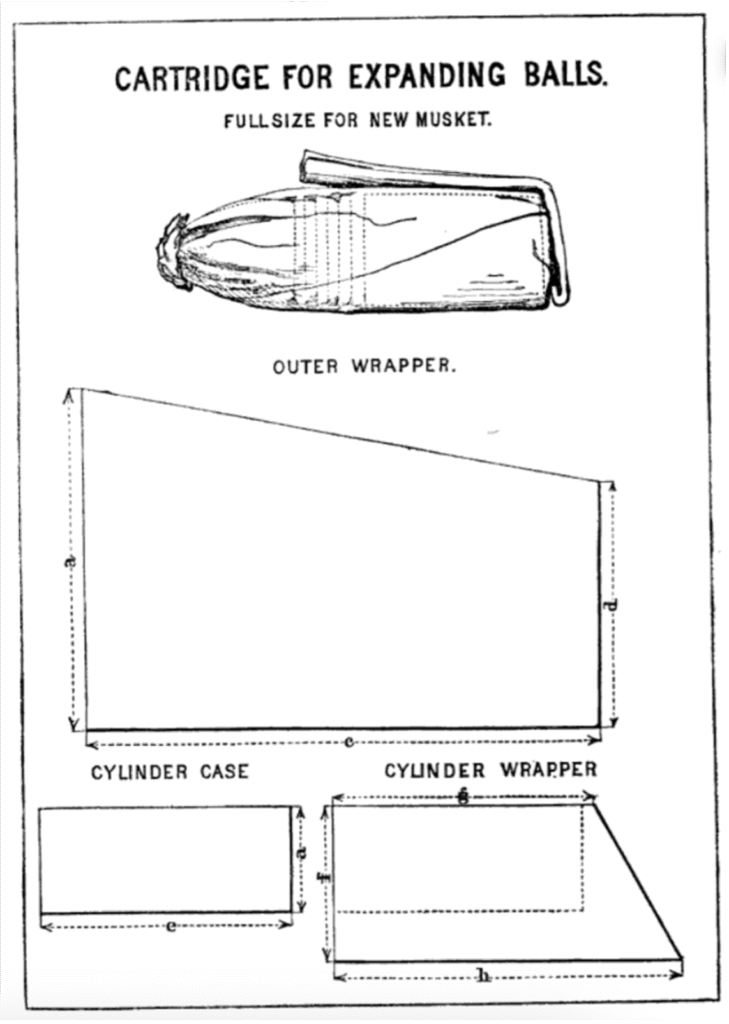

The standard rifle musket cartridge at commencement of the war was the U.S. Army’s Model 1855 cartridge, referred to by Confederate ordnance officers as the “Old U.S. Style.” This cartridge used three pieces of paper; a stiff cylinder case and inner wrapper folded under and glued at the bottom, with an outer wrapper enclosing both the bullet and powder cylinder. The outer wrapper was choked and tied at the tip of the bullet, the cartridge filled with powder, and the top of the cartridge “pinched” and folded. Most reenactors making “authentic” cartridges are unknowingly approximating this pattern but omit the inner wrapper and cylinder. By 1862, Federal ordnance authorities had developed a simplified cartridge using just two pieces of paper. The Confederacy, however, continued to use the Model 1855 pattern.3

Confederate inventors, however, sought less labor-intensive designs. Frederick J. Gardner, better known to living historians for his wooden canteen design, received Confederate Patent No. 12 in August 1861 for a new pattern of cartridge. Gardner’s cartridge machine crimped the base of the bullet over the bottom of the paper cylinder, allowing cartridges to be made quickly with a single wrapper without glue or tying. Gardner’s invention produced most of Richmond’s cartridges prior to January 1864 and was used to a lesser extent in Augusta and Charleston. Unfortunately for the living historian, the bullet was an integral, visible element of the Gardner cartridge, making it impossible to reproduce today as a blank cartridge.4

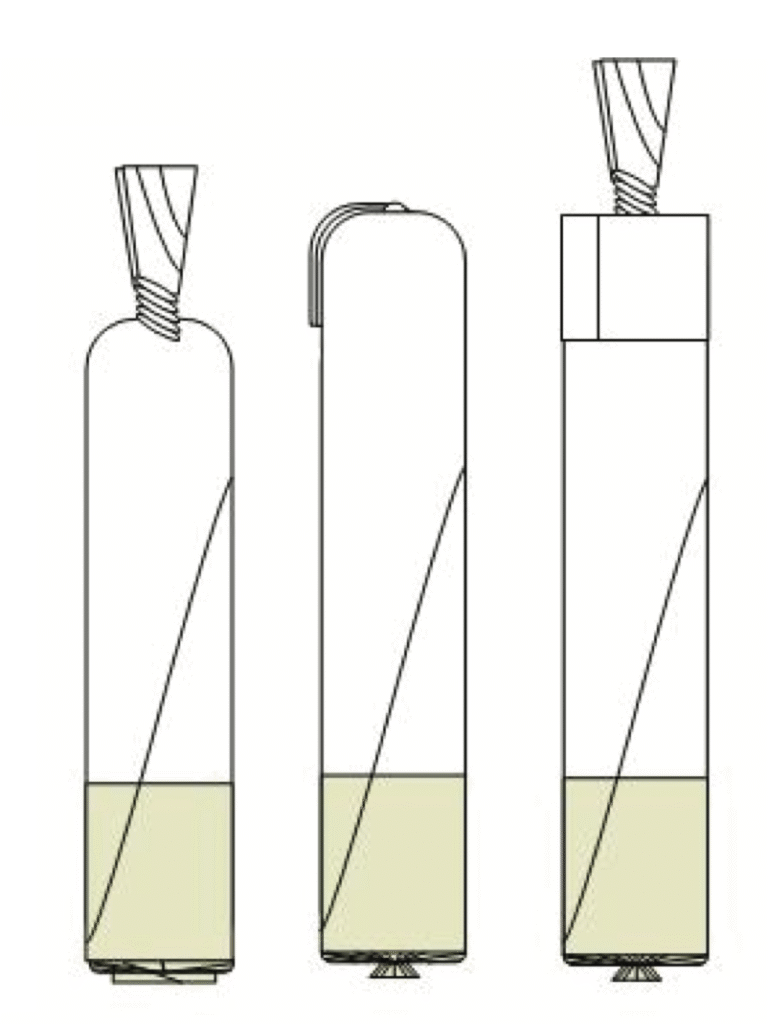

Despite the efforts of innovative southerners, the preeminent cartridge of the day was that designed in England for the Enfield rifled musket. The bullet was inverted relative to U.S. pattern cartridges and, since the bullet was loaded still wrapped in the paper, the bottom of the cartridge was lubricated with beeswax and tallow. By the Civil War period, the English cartridge used three wrappers, plus a glued paper band, and the top was twisted rather than folded. The earliest blockade runners carried English cartridges and the Confederacy continued to import and issue them throughout the war. One vessel, captured in 1862, was found to have 635,000 small arms cartridges onboard. Still, this cargo was only ten days’ worth of production at Richmond alone and domestic production would always outstripped imports. English cartridges are thus appropriate for most impressions other than very early war scenarios, but should not be overrepresented.5

Confederate Superintendent of Laboratories John W. Mallet strongly favored the English pattern and labored to make it the prevailing Confederate cartridge, despite having been initially ordered to make the Gardner cartridge standard. In August 1862, his Rules for Laboratories stated: “all cartridges for all muzzle-loading rifled arms… will be made of one uniform pattern, namely, that of the English Enfield rifle cartridges (with three wrappers).” Surviving examples reveal some Confederate-made English cartridges followed the latest design, while others utilized an older Model 1859 design that omitted the glued band and folding the top instead of twisting it, or blended the two designs. The current pattern called for three slits in the outer wrapper to facilitate separation of the bullet from the paper upon firing, but Confederate arsenals were frequently reprimanded for omitting this detail.6

Despite Mallet’s orders, arsenals continued to produce different styles of cartridge. Nearly a year after issuing his rules, Mallet reported Gardner cartridges, which Mallet judged too weak to withstand field use, were still being made at Richmond. Augusta also used the Gardner machine, as well as old U.S. style cartridges. Atlanta made exclusively old U.S. style rounds. Charleston made English cartridges and only discontinued use of the Gardner machine in May 1863. A smaller laboratory in Lynchburg used a design not seen elsewhere, a cartridge design patented by its Superintendent John W. Spillman that was exclusively folded without use of thread or glue. Macon, Columbus, and Selma appear to have been the most responsive to Mallet’s directives, with the English style cartridges made at Selma repeatedly winning praise as the best made anywhere in the Confederacy.7

Left to right: U.S. Model 1855 style cartridge, Macon Arsenal; Gardner cartridge, most likely made at Richmond; Commercial English cartridge, E & A Ludlow of Birmingham; English style cartridge, Augusta Arsenal; English style cartridge, Selma Arsenal (Courtesy, left to right, American Civil War Relics & Military Antiques, Heritage Auctions, American Civil War Relics & Military Antiques, Morphy Auctions, The Horse Soldier)

Left to right: U.S. Model 1855 style cartridge, Macon Arsenal; Gardner cartridge, most likely made at Richmond; Commercial English cartridge, E & A Ludlow of Birmingham; English style cartridge, Augusta Arsenal; English style cartridge, Selma Arsenal (Courtesy, left to right, American Civil War Relics & Military Antiques, Heritage Auctions, American Civil War Relics & Military Antiques, Morphy Auctions, The Horse Soldier)

The English pattern faced challenges to widespread adoption. Soldiers, used to removing the bullet from the paper while loading, required additional instruction on proper loading, as otherwise the bullet was too small for accurate fire. The English cartridge was also longer than American patterns and only in late 1863 did Mallet question whether his ammunition would fit in Confederate cartridge boxes and experiment with shortened rounds. Finally, since the thickness of the paper was factored into the diameter of the bullet, the English cartridge required a smaller diameter bullet and a consistent weight of paper to ensure the correct windage. Mallet requested the import of thin English “white fine” paper for making Enfield cartridges and thousands of reams were run in past the blockade. After the Bath Paper Company of Augusta, which had agreed in 1862 to provide the Ordnance Department a year supply of paper, burned to the ground on 2 April 1863, Mallet struggled to locate alternative suppliers. At one point he ordered Augusta to repurpose old account books if suitable paper could not be obtained. Mallet was ultimately forced use to smaller contracts with Millburnie Paper Mill and Forest Manufacturing Co. in North Carolina and Georgia’s Rock Island Paper Co. to supply the southern arsenals. Richmond, meanwhile, relied on the city’s own Franklin Mill, supplemented by the Buffalo Paper Mill in Shelby, North Carolina.8

Despite the challenges, Mallet appeared on the brink of a personal victory in early 1864. The Ordnance Department officially abolished use of the Gardner machine, much to Richmond’s frustration, and on 21 January 1864, Chief of Ordnance Josiah Gorgas declared “the English Enfield made with three wrappers will alone be allowed.” Some facilities were allowed to delay the switch until they exhausted their supply of paper already cut for old U.S. style cartridges. Mallet corrected small defects as facilities like Atlanta and Lynchburg switched to the new cartridge pattern.9

Then, abruptly, Gorgas issued a 19 March 1864 order suspending fabrication of English cartridges and directing adoption of the old U.S. style. His primary concern appears to have been that the length of English cartridges prevented the closure of cartridge boxes, exposing ammunition to the elements. Arsenals struggled to respond to the sudden change and Mallet obtained permission for limited production of English cartridges when appropriate molds were unavailable. Several U.S. style cartridges survive from various arsenals, likely from this period, and this pattern should predominate late war impressions.10

This article is only a short primer on the topic. Those seeking to learn more are directed towards Round Ball to Rimfire Part 4: A Contribution to the History of the Confederate Ordnance Bureau by Dean Thomas, A Handbook of Civil War Bullets and Cartridges, also by Dean Thomas, Percussion Ammunition Packets: Union, Confederate & European, 1845 – 1888 by John Mallory, Dean Thomas, and Terry White, and The British Cartridge: Pattern 1853 Rifle-Musket Ammunition by Brett Gibbons.

Endnotes

- John W Mallet to Josiah Gorgas, 7 May 1863, Letters Sent Superintendent of Laboratories, April 1863 – April 1864, vol. 24, ch. 4, Records Group 109, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Mallet to G W. Rains, 17 Aug 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent.

- Dean S. Thomas, Round Ball to Rimfire Part Four: A Contribution to the History of the Confederate Ordnance Bureau (Gettysburg, Thomas Publications, 2010), 70-71, 87.

- Reports of Experiments with Small Arms for the Military Service (Washington: A. O. P Nicholson, 1856), 114-116.

- Robert Gunderman and John Hammond, “The Confederate Patent Office,“ The Limited Monopoly (November 2015), 11; William N Smith, Compiled Service Records of Confederate General and Staff Officers, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (hereafter CSR); Mallet to Gorgas, 13 Jul 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent; John C Calhoun, CSR.

- C. L. Webster, Entrepôt: Government Imports Into the Confederate States (Edinborough: Edinborough Press, 2009), 33-34 and 37-38.

- Round Ball to Rimfire, 35 and 45; Mallet to Gorgas, 15 Aug 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent; Mallet to Gorgas, 18 Nov 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent.

- Mallet to Gorgas, 13 Jul 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent; Moses H Wright, CSR; John C Calhoun, CSR;Yorkville Enquirer, 31 October 1861; John R Spillman, CSR; “Confederate Patent Office,” 11; Round Ball to Rimfire, 89 and 97; Mallet to Gorgas, 17 Sep 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent.

- John W Mallet, CSR; Henry M Fitzhugh, CSR; CSR William N Smith, CSR; John W Mallet, CSR; Round Ball to Rimfire, 54; Entrepôt, 48, 105-108, 119-121, 123-124, 127; Bath Paper Company, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms (hereafter Citizens File), Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Athens Southern Banner, 10 April 1863; Mallet to Gorgas, 1 Jul 1863, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent; Neuse Manufacturing Co, Citizens File; Thos C Thackston, Citizens File; Rock Island Paper Mill Co, Citizens File; T J Stanford, Citizens File; Belvidere Manufacturing Co, Citizens File; Day Book and Abstract of Contracts, Ordnance Depot, Richmond, Virginia 1861-1863, vol. 96, ch. 4, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; W S Downer to D Froneburger & Co, 13 Feb 1863, Letters Sent, Ordnance Depot, Richmond, Virginia November 1862 – January 1864, vol. 90, ch. 4, Record Group 109, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Froneberger and Co, Citizens File.

- Downer to Rains, 7 Nov 1863, Richmond Letters Sent; William N Smith, CSR; Moses H Wright, CSR; Frederick L. Childs, CSR; Mallet to Gorgas, 7 Mar 1864, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent; Mallet to Gorgas, 16 Mar 1864, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent.

- Mallet to Gorgas, 2 Apr 1864, Superintendent of Laboratories Letters Sent; John C Calhoun, CSR; Round Ball to Rimfire, 147.