By Austin Williams, 5th VA, Co. A

We spend hundreds of dollars on the best available reproductions of Confederate uniforms and equipment. We spend hours pouring over period manuals to ensure our drill is precise down to the smallest detail. And then, when it is time to eat… out comes the modern food from concealed coolers. Even though preparing and eating authentic food is one of the cheapest and easiest ways to improve your impression, even many reenactors in progressive campaigner units fall back on modern food and coolers. Since many of us don’t cook much at home and have even less experience cooking over a fire without refrigeration, tackling period food can be intimidating. It also requires some planning and prep work to carry authentic food, but it produces a much richer and more authentic impression to be munching on corn pone and bacon than to be frying up a hot dog and heading to the vendor area for funnel cake.

To give you a sense of what food was available to soldiers in the Civil War, the official Confederate army ration was the following [1]:

-

- Either 3/4 lbs of pork or bacon; or 1 1/4 lbs of fresh or salt beef. This was latter modified to be 1/2 lbs pork/bacon or 1 lbs beef.

- 18 oz of bread or flour; or 12 oz of hard bread [hardtack]; or 1 1/4 lbs of cornmeal. This was later modified so that the ration of flour or meal would not exceed 1 1/2 lbs or either. The regulations also call for this ration to be changed to 1 lbs of hard bread on campaign, marches, or on board transports.

Then, for every hundred men, rations included:

-

- 8 quarts of peas or beans; or 10 pounds of rice

- 6 lbs of coffee

- 12 lbs of sugar

- 4 quarts of vinegar

- 1 1/2 lbs of tallow candles; or 1/4 lbs of adamantine candles; or 1 lbs sperm candles

- 4 lbs of soap

- 2 quarts salt

Union army rations were similar, but also included options for desiccated potatoes, desiccated mixed vegetables, and tea [2]. Of course, the actual amounts issued and the availability of these items fluctuated throughout the war. By 1864, rations in the Army of Northern Virginia rarely exceeded 1/4 lbs of beef or bacon and 1 lbs corn meal according to a variety of brigade and divisional inspection reports. By 1865, the Confederate Commissary Department wasn’t able to sustain even this amount, issuing either meat or bread each day, but not both. For reference, 1 lbs of bread or 3/4 lbs of meal a day provides only about 900-1200 calories, while the modern US Army considers 4,000 calories per day necessary to sustain an adult male in a combat environment [3]. Regardless of the amount, the regulations and actual Commissary Department practice suggest that the foundation of authentic rations should be a meat (bacon, fresh pork, fresh beef, or salted beef) and a starch (flour, cornmeal, hardtack, or bread). To this foundation can be added other issue items like rice, peas, beans, coffee, sugar, salt, vinegar, potatoes, or desiccated vegetables. You can then supplement these rations with small amounts of scenario-appropriate “foraged” items such fresh fruit/vegetable or items you might have plausibly purchased from a sutler or received from home, but avoid relying on these too much. Issued foods should form the core of your weekend rations.

The starch portion of the ration is usually easier for even novice cooks to prepare. Particularly if the scenario being portrayed is relatively static, carrying fresh bread is feasible, as Confederate armies utilized field ovens and civilian bakeries as a source of fresh bread. To simulate this in your rations, either bake your own bread or look for smaller, more artisan loafs at the grocery store that look like they could be homemade. Hardtack is relatively simple to make, is extremely easy to carry in a haversack, and, if prepared reasonably close to an event, won’t risk breaking your teeth quite as much as the original. The following recipe makes about ten pieces and is sufficient for a weekend event:

Ingredients:

4 cups flour

4 teaspoons salt

Water (less than 2 cups)

Instructions

Pre-heat oven to 375° F. Mix the flour and salt together in a bowl. Add just enough water (less than two cups) so that the mixture will stick together, producing a dough that won’t stick to hands, rolling pin or pan. Mix the dough by hand. Roll the dough out, shaping it roughly into a rectangle. Cut into the dough into squares about 3 x 3 inches and ½ inch thick. After cutting the squares, press a pattern of four rows of four holes into each square, using a nail or other such object. Do not punch through the dough. The appearance you want is similar to that of a modern saltine cracker. Turn each square over and do the same thing to the other side. Place the squares on an ungreased cookie sheet in the oven and bake for 30 minutes. Turn each piece over and bake for another 30 minutes. The crackers should be slightly brown on both sides.

However, period accounts suggest that the most common form of starch available to a Confederate soldier was cornbread. A Mississippi soldier grown tired of this recurring ration wrote to his sister in 1863 “I want Pa to be certain and buy wheat enough to do us plentifully, for if the war closes and I get to come home I never intend to chew any more cornbread.”[4] While experienced reenacting cooks can prepare corn dodgers over the fire, a good way to build your confidence with more authentic rations is to prepare cornbread before an event. Avoid the cornbread mixes in the grocery store, as they’re much lighter than what soldiers would have had and will crumble easily. The following cornbread recipe is delicious and survives transportation in a haversack mostly intact. Cook it in a cast iron skillet if possible and cut into four quarters prior to an event.

Ingredients

1⁄2 cup shortening

1 cup flour

1⁄4 cup sugar

3 teaspoons baking powder

3⁄4 teaspoon salt

1 cup cornmeal

3 eggs

1 cup milk

Instructions

Preheat oven to 425. While oven is heating, melt the shortening in a cast iron skillet. Mix dry ingredients. Add eggs and milk and mix well with electric mixer. Pour melted shortening into batter and blend until smooth. Pour batter into hot iron skillet and bake 20 – 25 minutes until golden brown.

While preparing an authentic starch is relatively straightforward, many reenactors struggle with incorporating meat into their rations without resorting to a modern cooler. While beef jerky and various sausages were certainly available in the period, they would not have been available in significant quantities and shouldn’t form the foundation of your rations. Instead, focus on the staples outlined in the official rations – bacon, pork, and beef. Double smoked slab bacon, also sometimes called country bacon, is available from some butchers or for purchase online and shouldn’t need refrigeration, particularly for the relatively short period of an event. Unless you have a local butcher that carries it, your best option may be to purchase a large slab, cut it into circa 3/4-1/2 lbs chunks, and freeze them either vacuum sealed or in individual plastic bags. Then, when it’s time for an event, you can simply pull a chunk of bacon out to defrost a few days in advance. Online options include this bacon from Broadbent’s, this from New Baunfels Smokehouse, or this from Edwards Virginia Smokehouse. As soldiers often cooked all of their rations upon issue rather than at individual mealtimes, you can pre-cook a portion of your slab bacon before an event and eat it cold, particularly if your Saturday lunch is hurried or eaten on the move.

Beans, dried peas, and rice are all light and easy to carry in a poke sack, particularly if an event includes marching from one campsite to another. Just keep in mind that dry beans and peas need to be soaked overnight before cooking them. Rice is perhaps the easiest to purchase and quickest to prepare, as a handful of brown “minute rice” in a mucket of water will quickly boil and provide a filling side dish. Dried peas and even desiccated vegetables can be found for purchase online. Finish off your ration issue with a poke sack of coffee beans and you’ll have most of the items listed in the official regulations.

Try to limit food that has been nominally sent from home, pilfered from a local farm, or purchased from a sutler. The bulk of soldiers, the bulk of the time, would have been forced to rely on issued food, particularly as armies picked Northern Virginia clean through several years of war and transportation of packages from home became increasingly difficult. These packages would be most prevalent early in the war while supplies were still plentiful on the home front and could include vegetables, sweets, butter, pickles, ketchup, apple butter, bread, potatoes, sausages, honey, or nuts. Units around Richmond early in the war even reportedly received shipments of fried chicken from home.[7] These packages did not necessarily disappear entirely by the end of the war – Private John Dull of the 5th Virginia Infantry wrote in January 1865 to his wife that, because multiple members of his mess had recently received packages from home, “we hav cabbitch potatoes Beans dried apples green apples flour meel pies cheas Bread cakes Sausage dried Beef chickon dried chearies cheary gam [cherry jam] molasos onions and evrey thing that house ceepers [keepers] generaley have excep wimon an children.” He wrote of having multiple hams hanging in his cabin, baking bread and biscuits, and selling surplus butter in Petersburg as they had more than they could use.[8] If possible try to match your non-standard issue food to the particulars of the unit and scenario you are portraying.

If, even in face of all the above options, you still want to incorporate some modern food in your weekend menu, do what you can to at least remove modern packaging and replace it with poke sacks, fabric, or paper wrapping to make it as unobtrusive as possible. If you want to use some can goods, there are lots of period can labels available online or for purchase through various sutlers to give your food a period appearance.

The skilled reenacting cook can combine the above ingredients into a dazzling array of dishes, but even novices can easily prepare simple meals using nothing more complicated than a mucket, canteen half, fork, knife, and spoon. Beef and bacon were commonly broiled, by simply skewering the meat with a stick or ramrod and roasting it over the fire (be aware that this technique could damage the weaker materials used in some reproduction ramrods). To avoid losing the valuable bacon grease from this method, try pan frying your bacon or beef in a small skillet or canteen half. The grease can be used to fry sliced potatoes or vegetables, but is also a fundamental ingredient of that uniquely Confederate dish, cush. A soldier in the Army of Tennessee provide the following recipe: “We take some bacon and fry the grease out, then we cut some cold beef in small pieces & put it in the grease, then pour in water and stew it like hash. Then we crumble corn bread or biscuit in it and stew it again till all the water is out then we have… real Confederate cush.”[9] Crumbled pieces of hardtack fried in bacon grease also tastes surprisingly good. You can mix together a variety of stews in a mucket or small pot. Just remember to add the ingredient which will take the longest to cook in first and progressively add the other ingredients as you get closer to completion.

Endnotes

- Confederate War Department, Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States, 1863, J. W. Randolph, Richmond, 1863; Article XLII, para 1107-1109.

- United States War Department, Revised Regulations for the Army of the United States, 1861, J. G. L. Brown, Philadelphia, 1861; Article XLIII, para 1191-1193.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T., General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse, Free Press, New York, 2008; p. 446.

- Wiley, Bell Irvin, The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 1943; p. 98.

- General Lee’s Army, p. 212.

- Life of Johnny Reb, p. 98.

- Life of Johnny Reb, p. 99-100.

- Augusta County: John P. Dull to Giney Dull, January 11, 1865, Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War, University of Virginia Library (https://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/A6131).

- Life of Johnny Reb, p. 104-105.

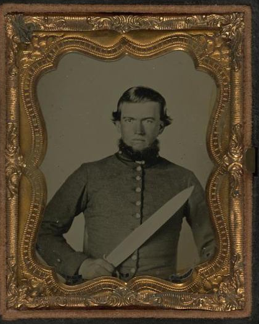

All photos are public domain from the Library of Congress’s Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints Collection.

1) Put the Credit Card Away: The absolute best advice anyone can give you is to delay purchasing any gear. Almost every reenactor can tell you stories about uniforms or equipment they rushed to purchase when they first started out and later regretted after they learned it was of poor quality or didn’t fit the impression they ultimately pursued. Any unit you’re interested in joining should be eager to loan you a uniform and equipment for your first few events (if they are not or if you’re pressured to purchase equipment right away, you’re probably considering the wrong unit). Before you start investing cash in reenacting, attend enough events to ensure that it’s a hobby that you truly enjoy and want to purse. Do not make the mistake of spending a lot of money on gear that ends up gathering dust in your basement or up for sale on eBay.

1) Put the Credit Card Away: The absolute best advice anyone can give you is to delay purchasing any gear. Almost every reenactor can tell you stories about uniforms or equipment they rushed to purchase when they first started out and later regretted after they learned it was of poor quality or didn’t fit the impression they ultimately pursued. Any unit you’re interested in joining should be eager to loan you a uniform and equipment for your first few events (if they are not or if you’re pressured to purchase equipment right away, you’re probably considering the wrong unit). Before you start investing cash in reenacting, attend enough events to ensure that it’s a hobby that you truly enjoy and want to purse. Do not make the mistake of spending a lot of money on gear that ends up gathering dust in your basement or up for sale on eBay. Progressive: These units occupy the middle of the authenticity spectrum. They may attend a combination of mainstream events, as well as more authentic, immersive events. They will likely incorporate some smaller “living history” events in their calendar which do not include a battle reenactment, but instead focus on portraying Civil War camp life for the public. They will make a concerted effort to ensure the authenticity of their uniforms, equipment, and drill, but are willing to accept some compromises as needed. They will also usually adapt their impression in some way to fit the unit and time period being portrayed, which often means you will ultimately need to purchase a wider array of uniforms and equipment. While there may be a few members of the group who conduct research using period primary sources, most members will rely more on reading contemporary secondary sources and the knowledge of their fellow reenactors to improve their impression. Most progressive units are also campaigner units, meaning that their camps will have minimal canvas and men are more likely to be sharing small tents or tent flies without any of the heavy cookware or furniture found in a mainstream camp. A campaigner should be able to pack more or less all their equipment on their back, whether just to carry his gear from camp to his vehicle or even for an extended march as part of the event. If you attend a reenactment as a spectator, you may have to work harder to find these units, as their camps are often placed farther from the public in wooded areas to limit the number of modern intrusions. The Stonewall Brigade is a progressive campaigner unit – click

Progressive: These units occupy the middle of the authenticity spectrum. They may attend a combination of mainstream events, as well as more authentic, immersive events. They will likely incorporate some smaller “living history” events in their calendar which do not include a battle reenactment, but instead focus on portraying Civil War camp life for the public. They will make a concerted effort to ensure the authenticity of their uniforms, equipment, and drill, but are willing to accept some compromises as needed. They will also usually adapt their impression in some way to fit the unit and time period being portrayed, which often means you will ultimately need to purchase a wider array of uniforms and equipment. While there may be a few members of the group who conduct research using period primary sources, most members will rely more on reading contemporary secondary sources and the knowledge of their fellow reenactors to improve their impression. Most progressive units are also campaigner units, meaning that their camps will have minimal canvas and men are more likely to be sharing small tents or tent flies without any of the heavy cookware or furniture found in a mainstream camp. A campaigner should be able to pack more or less all their equipment on their back, whether just to carry his gear from camp to his vehicle or even for an extended march as part of the event. If you attend a reenactment as a spectator, you may have to work harder to find these units, as their camps are often placed farther from the public in wooded areas to limit the number of modern intrusions. The Stonewall Brigade is a progressive campaigner unit – click  3) Do Your Research on Units: The current reality of the reenacting hobby is that every unit is eager, if not borderline desperate, to add new recruits to their ranks. Any unit you contact should be extremely welcoming and do everything they can to have you join their ranks. However, it is important that you find a unit that is a good match for you if you want to continue to enjoy reenacting over the long-haul. The unit you ultimately join should be in a position to provide the elements that you want to get out of reenacting. If you’re interested in an immersive, authentic experience, joining a mainstream unit will be a poor fit. Each unit also has a slightly different personality and quirks – they might be laid back or intense, their members may all have similar backgrounds and have known each other all their lives or they may be more diverse, they may be highly social at events and the life of the party or they may be more reserved. These characteristics can be challenging to identify by examining a unit’s website or Facebook page or by chatting with the members at an event. You may need to attend a handful of events with them before you get a good feel for the unit’s personality and whether it is a good fit for you. If it’s not, consider trying another group. If there were other units at the events you attended who seemed like a better fit for what you’re looking for, consider contacting them about falling in at their next event. You may want to speak candidly with your current unit’s commander about what you’re looking for in another unit, as they may have contacts or suggestions for other units that you can consider (if a unit commander isn’t willing to do this, its probably a sign you should leave that unit anyways, as they’re not looking out for your best interests). It is ultimately more important that you be happy and fulfilled in reenacting to ensure the hobby remains vibrant than for any particular unit to add an additional musket to the ranks.

3) Do Your Research on Units: The current reality of the reenacting hobby is that every unit is eager, if not borderline desperate, to add new recruits to their ranks. Any unit you contact should be extremely welcoming and do everything they can to have you join their ranks. However, it is important that you find a unit that is a good match for you if you want to continue to enjoy reenacting over the long-haul. The unit you ultimately join should be in a position to provide the elements that you want to get out of reenacting. If you’re interested in an immersive, authentic experience, joining a mainstream unit will be a poor fit. Each unit also has a slightly different personality and quirks – they might be laid back or intense, their members may all have similar backgrounds and have known each other all their lives or they may be more diverse, they may be highly social at events and the life of the party or they may be more reserved. These characteristics can be challenging to identify by examining a unit’s website or Facebook page or by chatting with the members at an event. You may need to attend a handful of events with them before you get a good feel for the unit’s personality and whether it is a good fit for you. If it’s not, consider trying another group. If there were other units at the events you attended who seemed like a better fit for what you’re looking for, consider contacting them about falling in at their next event. You may want to speak candidly with your current unit’s commander about what you’re looking for in another unit, as they may have contacts or suggestions for other units that you can consider (if a unit commander isn’t willing to do this, its probably a sign you should leave that unit anyways, as they’re not looking out for your best interests). It is ultimately more important that you be happy and fulfilled in reenacting to ensure the hobby remains vibrant than for any particular unit to add an additional musket to the ranks. 5) Purchase Slowly and Strategically: When you are ready to start purchasing gear, take your time and make your purchases strategic. Most units will be eager to help you select gear that fits with their authenticity standards and will offer up the unit commander, a non-commissioned officer, or another senior member to mentor you through your initial purchases. They should also have a list of recommended vendors that sell uniforms and equipment that meet their unit’s standards. For instance, the Stonewall Brigade’s list is located

5) Purchase Slowly and Strategically: When you are ready to start purchasing gear, take your time and make your purchases strategic. Most units will be eager to help you select gear that fits with their authenticity standards and will offer up the unit commander, a non-commissioned officer, or another senior member to mentor you through your initial purchases. They should also have a list of recommended vendors that sell uniforms and equipment that meet their unit’s standards. For instance, the Stonewall Brigade’s list is located

Assess Your Gear and Upgrade Slowly

Assess Your Gear and Upgrade Slowly The two items that are least likely to be “close enough” for temporary service are your jacket(s) and headwear. These are the two most prominent parts of a Civil War uniform and thus mainstream vs. progressive/authentic quality can be apparent from a distance. Mainstream sutlers are rife with jackets bearing little resemblance to the cut, fabric, or color of period uniforms. Unless you were a particularly luckier or better informed purchaser than most, odds are high that the jacket you purchased isn’t close enough to your new unit’s authenticity guidelines to pass muster. If you are building a progessive/authentic Confederate impression, you will likely eventually need to purchase

The two items that are least likely to be “close enough” for temporary service are your jacket(s) and headwear. These are the two most prominent parts of a Civil War uniform and thus mainstream vs. progressive/authentic quality can be apparent from a distance. Mainstream sutlers are rife with jackets bearing little resemblance to the cut, fabric, or color of period uniforms. Unless you were a particularly luckier or better informed purchaser than most, odds are high that the jacket you purchased isn’t close enough to your new unit’s authenticity guidelines to pass muster. If you are building a progessive/authentic Confederate impression, you will likely eventually need to purchase  Aim for Generic Nondescript

Aim for Generic Nondescript While progressive/authentic reenactors may pay more for individual pieces of gear, they generally own less equipment overall than their mainstream comrades and definitely bring less to an event. At most events, we are called upon to portray troops on campaign. While the large tents, wooden furniture, and heavy cast iron cookware that grace most mainstream camps certainly all existed in the period, as with uniforms you need to consider whether they are appropriate to the unit, time, and place being portrayed. Soldiers on campaign were almost exclusively reliant on their own backs to carry their gear and, thus, traveled light. As a general rule, if an event involves portraying troops on campaign, you shouldn’t be bringing more gear than you can carry, whether on the walk from the car to camp or on an extended march from campsite to campsite. Practice

While progressive/authentic reenactors may pay more for individual pieces of gear, they generally own less equipment overall than their mainstream comrades and definitely bring less to an event. At most events, we are called upon to portray troops on campaign. While the large tents, wooden furniture, and heavy cast iron cookware that grace most mainstream camps certainly all existed in the period, as with uniforms you need to consider whether they are appropriate to the unit, time, and place being portrayed. Soldiers on campaign were almost exclusively reliant on their own backs to carry their gear and, thus, traveled light. As a general rule, if an event involves portraying troops on campaign, you shouldn’t be bringing more gear than you can carry, whether on the walk from the car to camp or on an extended march from campsite to campsite. Practice