This is Chapter Four of a four chapter article. See Chapter One, Chapter Two, and Chapter Three. For a brief summary of this article, adapted to address the needs of living historians, see Blankets for Your Confederate Impression published in the ‘Living History Gazette.’

The Means in its Own Hands to Obtain all the Supplies Required

Luckily for Lawton, the summer and fall of 1864 would prove to be the apex of Confederate government blockade running, with overseas procurement and shipping functioning as efficiently as it ever would. Many of the vessel losses in Fall 1863 had been due to the siege of Charleston allowing additional Federal blockaders to focus on Wilmington. Now, Union forces loosened their grip on Charleston and reduced the size of the naval squadron off Wilmington. Blockade runners resumed operations into Charleston in June, reopening a second point of importation.1

The Confederate government had also made several changes to improve the effectiveness of their vital foreign operations. In September 1863, Seddon had designated Colin McRae the central coordinator for all overseas spending, with power to allocate funds between the various parts of the War Department vying for limited credit, cotton bonds, and hard currency. Creation of a Bureau of Foreign Supplies within the War Department under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas L. Bayne likewise centralized the government’s control of blockade running. As previously mentioned, in February 1864 the Confederate Congress passed legislation formalizing the government’s ability to demand half of the cargo space on incoming and outgoing vessels.2

These regulations, however, ultimately moved relatively little of the government’s overall cargo. Of 36 vessels that docked at southern ports between August and November 1864, only 9 operated under the February 1864 regulations. The rest were government owned steamers or contracted ships, like those contracted for with Power, Lowe & Co. and Davis & Fitzhugh. When the Power, Lowe & Co. contract came up for renewal in fall 1864, it was found the company had made 650% profit bringing in stores for the Quartermaster and Subsistence Departments.3

Contracted ships and ships sailing under the February 1864 regulations, however, still didn’t provide adequate capacity. As of August 1864, the Confederate government had access to roughly 2,000 tons of inbound cargo space monthly; the Subsistence Department alone estimated it needed 2,300 tons of cargo space monthly. By 1864, however, it was clear that the most effective way to bring in the War Department’s foreign purchases was via ships wholly owned by the government. McRae strongly favored direct government purchase of steamers. “I do not favor any partnership connections between the Government and individuals,” he wrote in July 1864. “If there be profits the individuals will get them; if losses, they will fall on the Government.” Rather than ships being jointly owned by the government and private companies, as the Crenshaw-Collie ships had been, he recommended the government buy-out the interests of other parties in these joint partnerships and run the steamers as government vessels.4

In spring and early summer 1864 McRae arranged with Fraser, Trenholm & Co. to purchase eight steamers. The first of these, the Bat and the Owl, sailed for Bermuda in August. Two more ships would be available in November, another two in December and the final two in April 1865. He signed a second contract with J. K. Gilliat & Co. for additional steamers, attempting to have two ready to sail by August. These too would be sent to Bermuda, where McRae understood “there is a large accumulation of Government freight.”5

Altogether, McRae purchased or contracted for 14 steamers by July 1864, “the best steamers now being built in the kingdom, and are greatly superior to most of the steamers heretofore engaged in the blockade business.” “By the end of the year,” he predicted, “the Government will have the means in its own hands to obtain all the supplies required abroad without incurring any further foreign debt.”6

In addition to contracts for ships, McRae finalized several large contracts for supplies in the spring and summer of 1864. In June James Tait renewed his offer for Peter Tait & Co. to supply uniforms to the Confederacy, raising the amount to 100,000 uniforms and shoes, but now offering fully assembled uniforms rather than kits. There was also no mention of the previously offered 50,000 blankets. Lawton again lent his support but reduced the number to the original 50,000 uniforms and sent the contract language to McRae.7

By the time this new proposal likely arrived, McRae had already made other arrangements. On June 13, McRae signed a contract with Alexander Collie & Co. to provide and ship to the Islands £150,000 of clothing and “general quartermaster supplies” to be purchased by Ferguson and £50,000 of ordnance stores selected by Huse. £50,000 of the quartermaster amount would go to Peter Tait & Co. to provide ready-made uniforms. Tait agreed to lower prices than those initially offered by his brother, as Alexander Collie paid him directly in cash. When the uniforms arrived in Wilmington on the Condor and the Evelyn in November and December 1864, however, surviving documentation makes no mention of blankets. Peter Tait & Co. did eventually sign an additional October 1864 contract directly with the Confederate government to provide 40,000 uniforms, but the contract made no mention of blankets.8

Blankets, however, almost certainly made up a significant portion of the remaining £100,000 worth of general quartermaster supplies Ferguson purchased under the contract. The first shipment under this contract sailed for Bermuda on the Falcon in late June, with the Flamingo following soon after. By July 4, Ferguson had already placed orders for the entire amount of the contract. A third Collie ship planned to sail in mid-July, a fourth in August, and all the supplies purchased under the contract were scheduled to be in the Islands by November.9

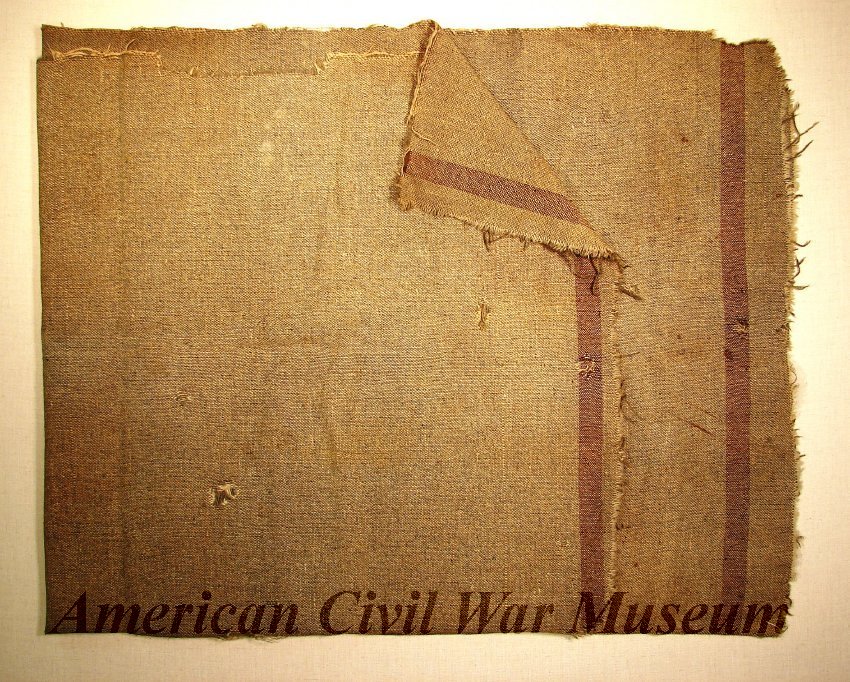

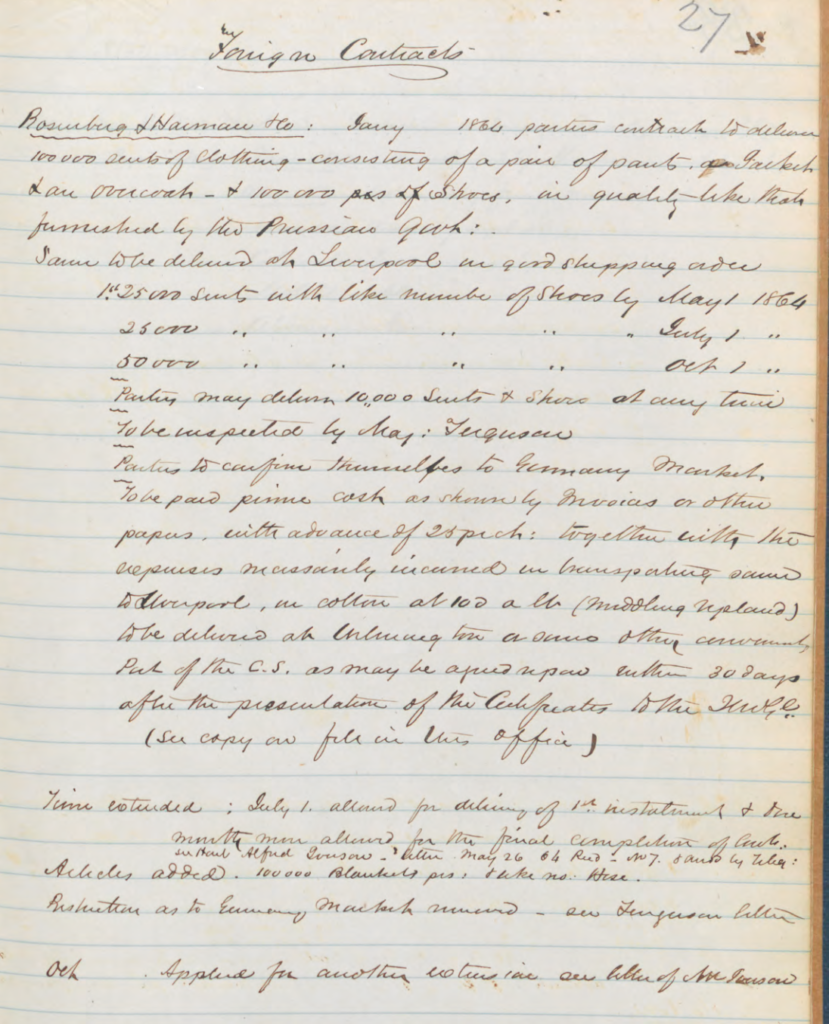

In addition to the Collie Contract, the Confederate government also signed a major contract for quartermaster supplies with Rosenburg, Haiman Bros. & Co. Louis and Herman Haiman, originally from Prussia, were major sword producers in Columbus, Georgia. Their bother Elias and their partner David Rosenburg represented the firm in Europe. The original contract in January 1864 was for 100,000 uniforms, overcoats, and shoes “in quality like that furnished the Prussian govt.” The contract originally limited procurement to the German market, likely so as to not compete with Ferguson’s work in England. Supplies were to be delivered to Ferguson in Liverpool ready to ship, a quarter by May, another quarter by July, and the remainder by October.10

In May, however, McRae reported having modified the contact to add 100,000 socks. Possibly around the same time, 100,000 blankets were also added to the agreement. Rosenburg, Haiman Bros. & Co. had engaged Liverpool shipping agent Henry Lafone, who had facilitated vessel purchase for several Confederate-aligned firms, to move their goods at the rate of £20 per ton. McRae reported that the combined goods from the Collie and Rosenburg Contracts would provide for 150,000 soldiers.11

In June, Ferguson reported that the Quartermaster Department “may expect with some certainty 1/4 of [the] goods under [the] Rosenburg contract.” This may refer to a shipment made by Lafone and others in April of 25,000 sets of uniforms, 25,000 pairs of shoes, and 50 pairs of blankets. The Bureau of Foreign Supplies reported delivery of £11,432 of supplies under the Rosenburg contact prior to July 1.12

Soon after, however, the firm began to encounter difficulty meeting the terms of the contract and was forced to request an extension of their delivery timeline. Then, in late July, things fell apart completely. Elias having returned to the Confederacy, Rosenburg sold out the contract to Lafone without the consent of his partners. Lafone then shifted the contract to Davis & Fitzhugh. Rosenburg received £20,000 to purchase quartermaster stores, but only purchased £3,000 while claiming the rest on the grounds that Lafone had failed to follow the terms of their agreement. Upon Elias’s return to Europe, Rosenburg fled to the United States. The Haiman brothers engaged Lafone to track him down, eventually recovering only £1,500 of the money. The increasingly complex matter was only resolved four years after the war through litigation. The drama prevented full delivery of the contracted goods by October as promised and necessitated a further extension. The collapse of the contract was likely a disappointment to Lawton, who wrote in September 1864 “I much prefer deliveries under the Rosenburg contract, and hope that they may not be superseded by the supposed advantages of the Davis & Fitzhugh contract.”13

Less is clear regarding the Davis & Fitzhugh contract. The company, along with Power, Lowe & Co., had held a large contract since fall 1863 to ship government freight, but the terms by which they provided material are less clear. By the end of July 1864, all the supplies requested by Ferguson under the Davis & Fitzhugh contract had been purchased. The following month, Thomas Bayne reported that the contract would deliver five or six cargos of general supplies to southern ports between August and October. Yet, Lawton found the firm’s products suspect. Inspection of the firm’s incoming cargos by the quartermaster in Wilmington found that “most if not all their deliveries have been purchased in the Islands.” When the Davis & Fitzhugh contract and the shipping contract with Power, Lowe & Co. expired in October 1864, they were not renewed.14

While Rosenburg, Haiman Bros. & Co. focused on the German market and Davis & Fitzhugh bought at least some of their goods in Bermuda and the Bahamas, Ferguson was hard at work with British manufacturers. Ferguson informed McRae in July that he could leverage government credit to enter into four and six month contracts with the blanket and heavy woolen producers of Lancashire and Yorkshire. McRae, seeking to limit overuse of debt, authorized Ferguson to exercise up to £40,000 in debt payable by the end of the year.15

Our Entire Supply of Blankets has to be Drawn from Abroad – Spring and Summer 1864

The efforts in Europe produced massive shipments across the Atlantic. The Ramseys landed in Bermuda in February with 18,098 blankets in its cargo hold. Some of this cargo was ferried into Wilmington on May 1 by the Helen, which landed with 102 bales of blankets. The Hackaway made Bermuda with 10,024 blankets in early April and all these blankets had been forwarded by mid-June. The Lucy unloaded 60 bales of blankets at Nassau on June 1. Some shipments to Bermuda were later transshipped to Nassau, with the Mary Celestiasailing for Nassau on May 23 with 77 bales of blankets and blue cloth, while the Florie sailed June 1 with 23 bales of blankets originally shipped from England in January aboard the Princess Royal. The brig Driving Mist, commissioned by the firm Widdecombe & Bell departed England on August 22 with a 165-ton cargo consisting of “large quantity of machinery, blankets, and clothing intended for the rebels,” according to the U.S. Consul in Liverpool.16

Blockade runners made increasingly regular trips back and forth between the Islands and southern ports. The Lillian landed 45 bales of blankets in Wilmington on June 5, then another 45 bales on June 24. The Florie, after having picked up additional blankets in Nassau, landed 67 bales on June 5 and then another 5,613 blankets on June 24. Surviving records detail the following shipments of at least 1,004 bales of blankets, or roughly 50,000 blankets, between June and August:17

| Date | Ship | Port | Blankets | Owner/Contract |

| 1 June | Lucy | Wilmington | 48 bales | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

| 2 June | Georgiana McCaw | Wilmington | 9 bales | M.G. Kilgender |

| 5 June | Lillian | Wilmington | 45 bales | Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia |

| 5 June | Florie | Wilmington | 67 bales | Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia |

| 9 June | Helen | Wilmington | 38 bales | Albion Trading Company |

| 11 June | Antonica | Charleston | 7 bales | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 12 June | Will O’ The Wisp | Wilmington | 8 bales (1,600 blankets) | Davis & Fitzhugh |

| 12 June | Coquette | Wilmington | 50 bales | Confederate Navy |

| 24 June | Lillian | Wilmington | 45 bales | Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia |

| 24 June | Florie | Wilmington | 56 bales | Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia |

| 27 June | Mary Celestia | Wilmington | 24 bales | Crenshaw & Co. |

| 1 July | Fox | Charleston | 13 bales | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

| 4 July | Let Her Rip | Wilmington | 39 bales | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 6 July | Syren | Wilmington | 39 bales | Charleston Importing Company |

| 11 July | Chicora | Unknown | 20 bales | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 11 July | Mary Celestia | Wilmington | 27 bales | Crenshaw & Co. |

| 30 July | Little Hattie | Wilmington | 12 bales | Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia |

| 15 July | Banshee II | Wilmington | Unknown | Davis & Fitzhugh |

| 5 August | Will O’ The Wisp | Wilmington | 40 bales (8,000 blankets) | Davis & Fitzhugh |

| 6 August | Mary Celestia | Wilmington | 27 bales | Crenshaw & Co. |

| 12 August | Chicora | Wilmington | 7 bales | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 13 August | Syren | Charleston | 30 bales | Charleston Importing Company |

| 23 August | Will O’ The Wisp | Wilmington | 40 bales | Davis & Fitzhugh |

| 24 August | Owl | Wilmington | 7 bales | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

| 27 August | Let Her Rip | Wilmington | 89 bales | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 29 August | Ella II | Wilmington | 117 bales (5,050 blankets) | Importing and Exporting Company of South Carolina |

| 30 August | Fox | Charleston | 100 bales (5,008 blankets) | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

For all the successful runs, some cargos were still lost. Off course in an attempt to reach Wilmington, the USS Quaker City and USS New Berne chased the Pevensey onto a beach near Beaufort on June 9. According to the captain of the New Berne, the Pevensey was “loaded on Confederate account, cargo consisting of arms, blankets, shoes, cloth, clothing, lead, bacon, and numerous packages marked to individuals.”18

As blankets arrived from overseas, Lawton sought to build up stockpiles in anticipation for the coming winter. In early June, the Richmond Clothing Bureau reported having 30,000 blankets on hand. 314 newly arrived bales of blankets from Wilmington were split, with half of the 63,800 blankets being sent to Augusta, Georgia and the other half to Columbia, South Carolina for storage until they were needed.19

Waller also continued to purchase in the Islands and accumulated significant debt in the process. In late June, Waller offered to purchase 300,000 yards of blankets “on as favorable terms as in England,” if funds could be made available. This was probably an offer from the firm Lamb, Austin & Co., as the following month Waller reported that the company had offered to sell the Confederacy £40-50,000 of supplies. McRae authorized Waller to make the purchases over the next four months. Much of these supplies were likely blankets, as Waller purchased 163 bales of blankets on August 4, amounting to 11,790 blankets. Just a few days later Waller dispatched the blankets as part of £20,000 of goods purchased from Lamb, Austin & Co. to Bermuda via the bark Architect. The following month Waller bought another 117 bales, or 5,350 blankets, from the company and shipped them via the Ella II.20

This was likely the last major blanket purchase made by Waller, as Lawton vetoed the initiative in September. He wrote on September 21 to McRae and Ferguson, stating that he had directed Waller to suspend further purchases, as Ferguson would be able to deal directly “with the manufacturers themselves to purchase better material and at lower prices.” McRae had noted earlier in the year that the goods obtained by Waller was 50% more expensive than those purchased in England and of inferior quality. Waller, Lawton now wrote, was already £30,000 in debt before he had begun purchasing from Lamb, Austin, & Co.21

Lawton was more direct in his letter to Waller and his tone is clear over 150 years later. “I think it advisable to be more explicit on one point,” Lawton wrote, “Do not on the authority received from Mr. McRae purchase further of the stock held by Mr. Samuel Austin.” Lawton explained that he might willing to take the whole £40,000 worth of supplies, if Lamb, Austin & Co. would accept payment in cotton. Since, however, they demanded British sterling, Lawton wrote, “I much prefer to leave the expenditure of all such means to Major Ferguson.”22

In late July and early August, the War Department’s bureau and department heads submitted their budget requests for the next six months. Lawton estimated the need to import 200,000 blankets in order to issue 100,000 blankets and store another 100,000 at the depots for future use. These blankets at $3 each would cost an estimated $600,000. Lawton noted that the scarcity of wool forced him to import half of the cloth required for his department, but “our entire supply of Blankets has to be drawn from abroad.” “To the extent that means can be provided,” he advised, “I believe it to be expedient to purchase abroad. The high prices at home & the inflation of currency consequent upon purchasing at these rates is thereby avoided.” The Quartermaster Department’s request also included $67,500 to pay off £15,000 of Waller’s debts in the Islands.23

Thomas Bayne likewise prepared an estimate for the War Department’s need for foreign currency over the next six months. This included £570,000 for the Quartermaster Department, the most of any of the departments. To meet the War Department’s need for foreign currency, more than 6,000 bales of cotton would need to be exported per month. In addition to these funds for direct purchases, he catalogued the government’s existing contracts; the Collie Contract for £150,000 worth of quartermaster storers, the Davis & Fitzhugh Contract that promised six cargos of general supplies by October, and the Rosenburg Contract for 100,000 uniforms and 100,000 shoes. While other contracts existed, “they are so indefinite that no calculations can be based upon them.”24

Having requested the necessary funds, in September Lawton confirmed that Ferguson was “fully advised as to [the Quartermaster Department’s] winter wants” and should “continue to press forward your purchases as rapidly as possible.” Ferguson, Lawton wrote, should prioritize shipping the “best quality of blankets, bluchers [shoes], and gray cloths, with a fair proportion of trimming.” Writing the same day to McRae, Lawton reported that “the diminished resource of the country make this department more than ever dependent upon the foreign supply, especially in connection with the articles of leather, stationary, and woolen materials of every description…”25

Adaptive Ingenuity or Dishonest Adulteration – The Shoddy Trade

Recalling how the loss of several ships the previous fall had so strained his department, Lawton also sought to recreate some of the South’s domestic blanket production capacity and reduce his total reliance on importation. In September 1864, he instructed Ferguson and Thomas Sharpe, another Quartermaster agent in England, to purchase four sets of machinery to weave blankets. Although the purchase would cost nearly £10,000, Lawton judged they “will prove an excellent investment, and they will serve to make the Confederacy independent of the foreign market and the contingencies of the blockade.” Lawton further instructed Sharpe to purchase the knowledge or hire someone knowledgeable of the process of extracting wool from rags and scrap cloth. Any process that could covert one ton of rags to half a ton of wool at a cost of one pence per pound “will prove of great value to the Confederacy.” If Sharpe was unsuccessful at acquiring this knowledge, Lawton instructed him to only purchase one set of blanket machinery, as there was insufficient wool within the Confederacy to provide the raw material for four.26

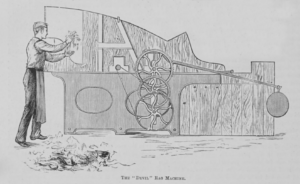

The privileged knowledge Lawton sought to acquire was that of the shoddy trade. Shoddy was made by tearing and grinding soft woolen rags, such as from stockings or flannels, into a pulp. This was accomplished with a device called a swift, or colloquially known as a “devil”, a spiked drum with as many as 14,000 teeth turning 600-1000 times a minute. The same process could be used with harder woolen cloth, such as worsted rags, and coarser teeth on the drum to produce a similar material called mungo. Shoddy and mungo could be mixed with a proportion of pure wool to create a less expensive fabric that had greater substance and warmth. The extreme shortness of the shoddy fibers, however, sacrificed strength and so shoddy was best suited for fabric where warmth was a premium, such as blankets and carpets.27

An 1858 British travel journal described the process, beginning with the operation of the swift: “There I saw a cylinder revolving with a velocity too rapid for the eye to follow, whizzing and roaring, as if in agony, and throwing off a cloud of light wooly fibers, that floated in the air, and a stream of flocks that fell in a heap at the end of the room… The cylinder was full of blunt steel teeth, which, seizing whatever was presented to them in the shape of rags, tore it thoroughly to pieces; in fact, ground it up into flocks of short, frizzly-looking fibre….”28

The fiber was next taken into the mixing room, where “the long fibre is mixed in certain proportions with the short; and… lightly sprinkled with oil…. A dingy brown or black was the prevalent colour; but some of the heaps were gray, and would be converted into undyed cloth of the same colour.”29

“Flocks are intimately mixed,” the journal continued, “by passing over and under a series of rollers, and come forth from the last looking something like wool. Then the wool, as we may now call it, goes to the ‘scribbling-machine’, which, after torturing it among a dozen rollers of various dimensions, delivers it yard by yard in the form of a loose thick cable, with a run of the fibres in one direction. The carding-machine takes the cable lengths, subjects them to another round of torture, confirms the direction of the fibers, and reduces the cable into a chenille of about the thickness of a lady’s finger.” This material was then wound on spindles and sent for spinning into yarn in the same manner of pure wool.30

The proportion of shoddy used relative to pure wool struck the balance between cost and quality. Common practice in the Yorkshire woolen mills by the Civil War period was to use one third pure wool mixed with two thirds shoddy or mungo. Particularly cheap blankets, however, might have as low as one part wool to six parts shoddy. As previously discussed, the surviving blankets imported by North Carolina appear to contain some shoddy, although the exact proportion is unknown.31

Views of this process were decidedly mixed. At an 1851 exhibition, the judges praised shoddy makers John Jubb, Hargreaves & Nussey, and Oldfield & Co. for their “general excellence of manufacture and great ingenuity in the application of new materials.” They called shoddy “a striking illustration of the adaptive ingenuity of the present day.”32

Others viewed the use of shoddy as deceitful and a sign of poor quality, calling it as a “dishonest adulteration” that used “a very inferior species of wool.” The Witney blanket makers refused to use shoddy and major Yorkshire blanket exporter Thomas Cook generally opposed its use. British military blanket contracts through at least 1858 prohibited the use of “shoddy, woollen waste, hair, or anything else but pure wool.”33

Much of the negative perception of shoddy could, at least in the British opinion, be traced to excessive use of shoddy by American industry during the Civil War. By using too high a proportion of shoddy to pure wool, contractors for the Federal government produced a cheap, weak material unable to withstand the rigors of use and undermining the reputation of shoddy. An English magazine in 1865 charged the Americans with changing the definition of shoddy to be “gilded ignorance, mock patriotism, wire-pulling, successful knavery, swindling, nay treason itself.” It described the experience of Union soldiers issued uniforms made almost entirely of shoddy: “They fade and rip, and burst apart, and drop to pieces, but the contractor feels secure. His fortune is made, let the soldiers shiver and curse as they may.”34

Regardless of the reputation of the industry, it had grown rapidly in the 1800s. Cotton rags had long been used to make paper, but prior to the invention of shoddy, wool rags were considered relatively useless. While several people appear to have developed the idea of recycling woolen rags to make new cloth, Benjamin Law has traditionally received credit for first developing shoddy in 1813 in the Yorkshire town of Batley. The town and its surrounding district emerged as the center of the shoddy industry and remained so through the Civil War period.35

The novel new material was increasingly incorporated into cloth and blanket production throughout the 1820s, During this early period, even some manufactures who would later reject shoddy experimented with the novel material. Thomas Cook, later strongly opposed to the use of recycled wool, sometimes used shoddy in the 1820s from surplus British military grey and white blankets, because he considered the shoddy produced from them to be a higher quality.36

An American protective tariff in 1828, designed to promote domestic textile production, had the indirect effect of helping fuel the growth of shoddy in England. The tariff excluded blankets and cheap cloth under 50 centers per square yard, exactly the goods best suited for shoddy. Depressed economic conditions in England in the 1830s further increased demand for inexpensive cloths and the expanded use of shoddy allowed Yorkshire textile firms to flourish during this decade. This decade also fueled the initial view of shoddy as a dishonest substitution. Some manufacturers sought to maximize short-term profits by flooding the domestic and American export markets with interior products, fraudulently passing them off as pure wool. Men like Gott and Cook, who prided themselves on the high quality of their products, turned away in disgust from shoddy, despite having previously viewed it as a legitimate raw material for inexpensive blankets.37

The industry continued to grow in the 1840s and 1850s, as use of shoddy became extremely widespread in the Yorkshire trade. The introduction of the sewing machine in the late 1840s fueled the rise in ready-made clothing, which in turn drove up demand for inexpensive cloth containing shoddy. The 27 million pounds of shoddy and mungo produced annually in England in the 1840 exploded to 85 million pounds annually in the 1850s. The economic boom also drew more people to Batley, with the population of the village doubling between 1841 and 1861. Shoddy remained largely concentrated in Yorkshire, giving them an edge that facilitated dominance of the American markets, as there was almost no shoddy production in the United States prior to the Civil War. American shoddy was viewed with distain by British shoddy makers, believing it to be “loaded with cheap, short, and unskillfully blended shoddy” containing broken cotton warps.38

On the eve of the Civil War, there were few blanket producers in Yorkshire not using shoddy. Batley remained the center of the industry, with at least 61 rag merchants and dealers operating in Batley, Dewsbury, and Ossett in 1861. These firms sorted rags by color, quality, and hardness, as well as preparing them for grinding by cutting off seams. The concentration of blanket producers in Earlsheaton had previously produced all-wool blankets and still did so in support of British government contracts, but the majority of the blankets they made for the American export market used shoddy. Heckmondwike, adjoining Batley, also consumed large amounts of shoddy, but not as much as Earlsheaton.39

A confluence of multiple factors combined during the Civil War period to produce boom times for the shoddy trade. Large numbers of sheep had died during an 1859 drought, reducing domestic wool supplies and driving up the cost of new wool. Around the same time, an 1860 Anglo-French commercial treaty had opened new sources of woolen rags imported from France. The surge in demand by Federal and Confederate agents for blankets and cloth further drove up the cost of pure wool and the high cost of cotton relative to wool due to the Union blockade further encouraged an increased reliance on shoddy.40

By 1863, shoddy had driven “much of the present prosperity and extension of the Yorkshire trade,” while making the area around Batley and Dewsbury the “most prosperous parts of the woollen district.” Batley had 50 rag engines operating in 35 mills producing alone 12 million pounds of shoddy and mungo annually.Overall, England produced on average 46 million pounds of shoddy and mungo annually during the war years and consumed 66 million pounds. Exports grew by 40% by 1863 and by nearly 100% by 1865.41

The dominance of shoddy during the war was such that, in 1863, a sales agent for Benjamin Gott pleaded for his boss to reverse his prohibition against the use of shoddy: “You must make up your mind… [and] put a certain quantity of shoddy in your black cloths… but not so much as will interfere materially with the strength. This you must do, or you cannot compete with good houses… I know the use of shoddy is very objectionable to you, but if the spirt of competition drives you to it you must do it or be driven out of the market….”42

These boom times, however, were short-lived. Tariffs and development of the American shoddy industry during the conflict broke the Yorkshire dominance of the trade by war’s end. The American markets were virtually closed via tariffs immediately following the conflict and overall British shoddy exports fell as low as 4.3% by 1868. The number of shoddy firms forced to declare bankruptcy spiked sharply. Shoddy prices would not reach Civil War-era prices again until 1910.43

The shoddy engines, blanket looms, and other associated machinery ultimately located by Ferguson and Sharpe would produce 250-300 pairs of blankets daily and could be operated by three skilled men and a workforce of “negro labor and disabled soldiers.” The blankets, weighing nine pounds per pair, were made of 50% shoddy, 25% wool, and 25% cotton warps. The Quartermaster Department’s clothing bureaus could provide the wool scraps and rags needed to produce the shoddy. The 37,500 blankets produced annually would be roughly equal to those being purchased in Nassau.44

Sharpe had originally been sent to England to purchase machinery to manufacture shoes, making it difficult to determine which shipments of English machinery were for this original mission or for shoddy and blanket production. In September, the first set of machinery purchased was loaded in Liverpool aboard the Bat, one of McRae’s newly purchased side-wheel steamers for the Confederate government. During its approach to Wilmington on October 10, it was spotted and chased by two Union blockaders. A third warship, the USSMontgomery, fired a shot from a 30-pounder rifle that took off the leg of an Austrian seaman, mortally wounding him. After boarding their prize, the Federal sailors reported its cargo as “machinery for manufacturing shoes.”45

A second set of machinery arrived in December aboard the Owl and was sent to Augusta to be operated by Union prisoners. On January 6, 1865, the third and final shoe machine landed in Wilmington inside 44 cases carried by the Stag. Researchers David Burt and Craig Barry suggest that, amidst this shoe machinery, the shoddy machinery ordered by Lawton was also imported on the Stag, and while this is possible, surviving records only directly address the shoe machinery. As late as February 1865, however, a senior quartermaster reported that blanket machinery had been ordered overseas but made no mention of its arrival, suggesting that it still had not been fully delivered as of that date.46

Enough to Make the Army Not Only Efficient but Comfortable – The Final Months

While optimistic that shoddy would alleviate his future needs, Lawton informed Seddon in October that “blankets, shoes, and woolen goods have to be drawn in large quantities from abroad” to meet current demand. Large quantities are exactly what Lawton’s overseas network provided. Some ships were lost in transit, like the Hope that was captured in October while carrying 23 bales to blankets. Many more, however, reached Wilmington and Charleston. Between September and January 1865, as least 786 bales of blankets were offloaded on southern wharfs. Some of these shipments were massive, with the Fox delivering 10,000 blankets on September 28 and Ella II landing the following day with another 5,850. The following is based on surviving documentation:47

| Date | Ship | Port | Blankets | Company |

| 27 September | Wando AKA Let Her Rip | Wilmington | 39 bales (2,500 blankets) | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 28 September | Fox | Charleston | 100 bales (10,000 blankets) | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

| 29 September | Ella II | Wilmington | 117 bales (5,850 blankets) | Importing Company of South Carolina |

| 4 October | Talisman | Wilmington | 18 bales (1,890 blankets) | Albion Trading Company |

| 9 October | Syren | Charleston | 72 bales (3,600 blankets) | Charleston Importing Company |

| 10 October | Fox | Charleston | 49 bales | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

| 25 October | Lucy | Wilmington | 16 bales (800 blankets) | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

| 4 November | Hansa | Wilmington | 52 bales | Alexander Collie & Co. |

| 5 or 7 November | Julia | Charleston | 25 bales | Donald McGregor |

| 7 November | Chicora | Charleston | 16 bales (800 blankets) | Chicora Importing and Exporting Company |

| 8 November | Talisman | Wilmington | 7 bales | Albion Trading Company |

| 1 December | Owl | Wilmington | 161 bales | Confederate Government |

| 2 December | Caroline | Wilmington | 10 bales | Importing and Exporting Company of South Carolina |

| 4 December | Stag | Wilmington | 10 bales | Confederate Government |

| 4 December | Hasana | Wilmington | 52 bales | Alexander Collie & Co. |

| 9 December | Talisman | Wilmington | 37 bales | Albion Trading Company |

| 18 January | Fox | Charleston | 6 bales (44 bales thrown overboard in transit) | Fraser, Trenholm & Co. |

The scope of the importation effort in 1864 was truly impressive. In early December 1864, Seddon updated Davis on the War Department’s foreign operations. Between November 1, 1863, and October 26, 1864, Seddon reported the importation of 2,921 bales of blankets into Charleston and Wilmington or approximately 292,000 pairs of blankets. An additional 322 bales were brought in between October 26 and December 8, for a total of 3,243 bales. According to Seddon, the Quartermaster Department estimated these shipments had delivered 316,000 pairs of blankets. Modern analysis by scholar C.L. Webster identified at least 82 ships landing in Wilmington and Charleston between April 1864 and late December 1864. Webster’s research accounted for at least 169,868 pairs of blankets imported from these vessels, although an accurate tally is nearly impossible due to lost documentation, conflicting records, and variation in the number of blankets per bale.48

In December, Lawton responded to several November requisitions submitted by the Chief Quartermaster of the Army of Northern Virginia, noting that he had waited to respond until additional blankets and other supplies had arrived from Wilmington and Columbia. He expressed surprise at learning of the great need of the troops. Based on the issues made to the Army, as well as a lack of requisitions, Lawton had been under the impression the Army had been receiving “enough to make the army not only efficient but comfortable.” At any time in the past two months, Lawton wrote, sufficient stores were on hand to supply any article except overcoats. The Richmond Clothing Bureau had “a fair supply” of blankets and more had been stored in Wilmington and Columbia. Lawton immediately dispatched 10,000 blankets, plus those recently arrived, and invited further requests “for whatever you may need, either in the way of shoes or blankets, between now and the end of the quarter to make the army comfortable.”49

The efforts of Lawton, Ferguson, Waller, McRae and others ensured a continued flow of blankets to Confederate armies in 1864, despite the total reliance on foreign importation and the challenges presented by the Union blockade. In the final six months of 1864, the Quartermaster Department reported the issue of 156,092 blankets, including 74,851 to the Army of Northern Virginia, 4,924 to the Army of Southwest Virginia, 12,429 to the Department of South Carolina, Florida, and Georgia, 27,900 to the Army of Tennessee, 27,292 to the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, and 6,696 to the Department of North Carolina.50

For all this success, however, Lawton’s department remained entirely dependent on the continued operation of the south’s last two major Atlantic ports. The Union capture of Fort Fisher on January 15, 1865, spelled the beginning of the end. After the fort’s capture, the Federal Navy kept lit the light used to signal blockade runners, hoping to seize any ships that had not yet heard of the fall of the fort. On the night of 19 to 20 January, the Confederate government-owned Stag and the Charlotte both arrived from Bermuda and were quickly captured. Their cargo holes contained blankets, arms, shoes, and other material. Five nights later, the Blenheim also fell into the trap. She had sailed from Nassau loaded with blankets, shoes, and hats. A small number of ships managed to slip into Charleston until it too fell on February 17. With the closure of these ports, Confederate efforts to import blankets along the Atlantic coast came to an abrupt end.51

Lawton’s department struggled to continue following the loss of Wilmington and Charleston. In early February the state of Alabama offered to sell to the Confederate Government blankets the state had imported at a rate of $10 per blanket, to be paid for via 20 pounds of cotton. Lawton still dreamed of resumed domestic blanket production. One of his subordinates reported that the primary challenge would be acquiring adequate wool. While some manufacturing facilities existed for weaving woolen cloth, even this produced little due to deficiencies in raw materials. As for blankets, “the blankets now in the hands of the soldiers,” he wrote, “must be turned in in the spring for reissue. As there is not in the entire Confederacy a single establishment that makes them, machinery has been ordered from abroad.”52

Lawton’s shoddy machinery, however, would either never arrive or at least never become operational. Almost entirely cut off from outside supplies and without domestic production, it is questionable whether the Quartermaster Department would have been able to adequately supply southern armies even had Richmond not fallen in April 1865, followed soon after by the surrender of the two primary Confederate field armies and the total collapse of the Confederacy.

Confederate soldiers had, for four years, huddled for warmth under a wide array of blankets. Some were domestically woven by firms like Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. or the Crenshaw Woolen Company. Some were donated by southern civilians or were reissued Federal blankets. Some were made of repurposed carpet or improvised from jean wool and cotton shirting. Hundreds of thousands of them, likely the majority of them, were imported from Europe and run in past the blockade. Most of these imports came from England, with smaller numbers from France or the German states. After shoes, no other item was imported in larger numbers than blankets. Despite myriad challenges, the Confederate Quartermaster Department performed admirable work in their attempts to provide every Confederate soldier the comfort of a warm blanket.

Footnotes

- Goff, p. 147.

- Ibid., p. 180 and 278.

- Ibid., p. 182.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 527-528 and 590.

- Ibid, p. 525.

- Ibid, p. 526.

- Letter from Alexander R. Lawton to Colin McRae, June 28, 1864, Letters and Telegrams sent by the Confederate Quartermaster, 1861-1865, quoted in Barry and Burt, Suppliers Vol II, p. 184.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 526; Webster, p. 125 and 128; Peter Tait and Co., Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 526 and 529-530.

- “Columbus, Georgia,” Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities, accessed September 8, 2024, https://www.isjl.org/georgia-columbus-encyclopedia.html; Memorandum Book, p. 27.

- Memorandum Book, p. 24.

- Memorandum Book, p. 24-26; Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 590.

- Memorandum Book, p. 24 and 26-27; Webster, p. 100; N.J. Hammond, Reports of Cases in Law and Equity, Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Georgia, at Atlanta, Parts of June and December Terms, 1869, vol. XXXIX (Macon, GA: J. W. Burke & Co., 1870), p. 708-712; Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 673.

- Memorandum Book, p. 25; Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 675, 738, and 781.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 527.

- Memorandum Book, p. 6-7; Vandiver, p. 131 and 133; Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 10, p. 439.

- Memorandum Book, p. 6, 36-38 and 55-58; Webster, p. 118-123; While the number of blankets in a bale differed, a note in a memorandum book maintained by the Bureau of Foreign Supplies specified 25 pairs of blankets per bale.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 10, p. 137.

- Memorandum Book, p. 21.

- Memorandum Book, p. 47-48 and 54.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 673-674; Memorandum Book, p. 24.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 675.

- Alex R. Lawton, Compiled Service Records of Confederate General and Staff Officers, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Bayne Service Records; Memorandum Book, p. 42.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 589-590.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 673-674.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 673 and 683.

- William Gibson, “Wool and Worsted IX Shoddy and Mungo,” Great Industries of Great Britain, vol. 1 (London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co, 1884), p. 315-316; Jubb, p. 19-20; Fairborn, p. 265.

- Walter White, A Month in Yorkshire (London: Chapman and Hall, 1858), p. 353.

- White, p. 354.

- White, p. 355-356.

- Fairborn, p. 265.

- Malin, p. 405.

- Fairborn, p. 265; Glover, Government Contracting, p. 49; Report of the Commissioners, p. 608.

- The Cornhill Magazine, vol. XII, July to December1865 (London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1865), p. 44-45.

- Gibson, p. 314; Jubb, p. 17.

- Malin, p. 110.

- Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 574; Malin, p. 339.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 243; Heaton, p. 65; Royal Commission on Water Supply, p. 13; Malin, p. 226, 394-395 and 543.

- Gibson, p. 314; Jubb, p. 52, 130, and 132.

- Gail Louise Jenkins, “To What Extent Does the Town of Keighley Reflect the General Pattern of Growth, Stagnation and Decline in the West Riding Wool Textile Industry, 1851 to 1881” (Master’s dissertation, Open University, 2023), p. 13; Marlin, p. 416 and 422; Jenkins, p. 13.

- Fairborn, p. 265-266; Marlin, p. 266 and 601; Jenkins, p. 13.

- Heaton, p. 66.

- Marlin, p. 47, 266, 418, 420, and 486.

- Memorandum Book, p. 46.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. II, Vol. 2, p. 720; Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 10, p. 548; Memorandum Book, p. 46.

- Wilson, p. 178; Webster, p. 178; Memorandum Book, p. 58.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 716; Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 716 and 955-958; Wise, p. 279; Memorandum Book, p. 55 and 57-58; Webster, p. 124-127 and 153; Bayne Service Records.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 930 and 955; Memorandum Book, p. 56-58; Webster, p. 178.

- Official Records, Ser. 1, Vol. 42, p. 1268-1269.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 1041.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 11, p. 620, 623, and 700.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 1077 and 1090.

Absolutely superlative work. This article was a fantastic read and I learned a great deal. Thank you for sharing your knowledge!

Thanks Dan – really appreciate the kind words! Glad you enjoyed it.