By Austin Williams, 33rd VA Co. H

This is Chapter One of a four chapter article. See Chapter Two, Chapter Three, and Chapter Four. For a brief summary of this article, adapted to address the needs of living historians, see Blankets for Your Confederate Impression published in the ‘Living History Gazette.’

Of all the items the Confederacy struggled to provide its armies, few presented as much of a challenge as putting adequate wool blankets in the hands of Confederate soldiers. Despite blankets being an essential piece of equipment for the health and comfort of soldiers, the Confederacy went into the war with only limited ability to produce blankets and all that domestic capacity had been lost by mid-war. The Confederate Quartermaster Department had to rely heavily on blankets imported from the thriving English blanket industry to provide adequate supplies to the Army of Northern Virginia and other field armies. Yet, despite all the challenges it faced, the Quartermaster Department eventually developed a highly successful foreign operation, importing at least 440,000 blankets and making blankets the second most numerous imported quartermaster good after shoes. Lee’s army was the recipient of a significant portion of these blankets.1

From the beginning of the conflict, it was apparent the South would struggle to provide enough blankets for its emerging armies. On May 13, 1861, the first Confederate Quartermaster General, Abraham Myers, wrote to Secretary of War Leroy Walker with his assessment of the challenge faced and a recommendation. “I apprehend, from attention to the subject and inquiry among intelligent merchants,” wrote Myers, “that the resources of the Southern States cannot supply the necessitates of the Army of the Confederate States with the essential articles of cloth for uniform clothing, blankets, shoes, stockings, and flannel. I respectfully suggest that measures be taken to obtain these articles from Europe.”2

Myers proposed the Quartermaster Department send agents to Europe to purchase blankets, much as the new Ordnance Department was then doing to obtain arms and munitions. Unlike the Ordnance Department, however, Myers did not press the matter and waited on the Secretary of War for a decision, which did not come. Confederate leaders optimistically believed state and private efforts would provide adequate blankets, shoes, and wool cloth for the brief war most predicted. Myers, however, judged these efforts would fall short and responsibility of providing blankets would ultimately fall to him. He dispatched purchasing agents across the South to buy up available stocks of blankets and shoes. He also turned to the Confederacy’s textile industry to seek domestic sources of production.3

Never Heretofore Made in Virginia – The Crenshaw Woolen Company

The overall American antebellum blanket industry was relatively weak, with consumers relying heavily on imported British blankets. English producers had cornered the American market starting in the 1820s, meeting growing demand for inexpensive, low-quality blankets. One British manufacturer bemoaned in 1825 how “the verist rubbish” sold best in the United States and called the products being exported “hateful to look at by those who recollect what formerly went to America.”4

Blanket production began to pick up in the United States in the mid-1840s, but American manufacturers still operated at a distinct disadvantage to their British competitors. The United States in the mid-1800s produced relatively limited supplies of the coarse wool required for heavy woolen blankets, while British manufacturers had both an abundant domestic supply and ready access to cheap wool from Europe. By 1859, Great Britain was still exporting over 55 million yards of blankets, heavy woolens, and wool carpets annually to the United States. All American industry combined in 1860 produced just 296,874 pairs of blankets or roughly a million yards. A January 1861 advertisement by Richmond auctioneer Alex Nott for English Yorkshire blankets is representative of the British dominance of the pre-war blanket market in what would soon be the Confederate States of America.5

As with other industries, much of the growth in American blanket production in the 1840s and 1850s occurred in the North. Over 66 percent of blankets woven in American in 1860 were made in New England, and the entire South produced only 1,650 pairs of blankets that year. John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry in 1859, however, had stimulated Southern business to pursue the dream of “commercial independence” from Northern textile firms. Several Richmond businessmen, including Lewis D. Crenshaw, Samuel P. Mitchell, Wellington Goodin, John H. Montague, and P. W. Harwood, announced in 1860 the establishment of the Crenshaw Woolen Company, outlining the objective of their firm as making “such Goods as would not compete with, but would rather aid other Southern manufactures by furnishing grades and styles of Goods that have never heretofore been made in Virginia.”6

Crenshaw and his partners obtained an imposing five story brick building along the south side of the Richmond Canal, immediately adjacent to the Tredegar Iron Works. They converted this former flour mill to textile production, installing the finest quality machinery available, including the extra broad looms required to weave blankets. The mill entered initial limited production in August and immediately began to earn praise for its products. In October the Virginia Mechanics’ Institute awarded Crenshaw Woolen Company a silver medal for “superior all wool Blankets” and in November The Daily Dispatch reported the growing popularity of Crenshaw’s fabric, which was “being worn by all who can get them.” “Not only are they superior to most of the manufactories received from the North,” continued the paper, “but they are equally cheap and far more beautiful. More than that – they are ‘home made’ and should be adopted and worn by every class of citizens.”7

The Crenshaw Mill entered full production in December 1860 and local dry goods merchants Samuel M. Price & Co. and Watkins & Ficklen began offering Crenshaw’s “superior bed blankets made in our own city.” On the same day Virginia left the Union, April 17, 1861, the mill’s retail agent, Crenshaw & Co., began directly advertising the firms’ products in the Richmond papers. “Encourage southern manufacturers” they proclaimed, reporting their weekly production as 4,000 yards of cloth per week and having on hand “20,000 yards of Fine, Plain, and Fancy Single and Double Milled CASSIMERESE and CLOTHS, besides a lot of FINE BLANKETS and GENTLEMEN’S SHAWLS.”8

Prior works on the subject of Confederate blankets have stressed the importance of the Crenshaw Woolen Company in supplying the Confederate Army with blankets, primarily citing an October 17, 1861 article in the Richmond Enquirer. The paper praised the Crenshaw Mill as “second in importance as an auxiliary to Southern independence, scarcely to the Tredegar Iron Works, and the Virginia armory.” The mill was reportedly producing about 450 blankets a week, measuring 60 inches by 80 inches, made entirely of wool, and weighting 3 7/8 pounds. The Enquirer claimed Crenshaw was working exclusively on government contract and that “large numbers [of their blankets] have already been furnished to the army, are quite equal to the English army blankets, which are made of shoddy, and superior to those of the Yankees.”9

The Enquirer, however, was mistaken. While Crenshaw was operating exclusively under contract at the time, these contracts were not with the Confederate government. When war broke out, the Crenshaw Mill had produced $63,000 worth of goods since they began operation, but had sold only $13,000 worth, leaving them with a significant accumulated stockpile. In May or June 1861, a senior official from the Confederate Quartermaster Department contacted the Crenshaw Woolen Company requesting they provide a sample and propose a contract to supply the Confederacy with “a suitable army blanket.” The mill quickly complied, producing a sample four-pound blanket and proposing to sell 20,000 to the Quartermaster Department for $3.25 each, half paid in Confederate bonds.10

The Quartermaster Department, however, rejected Crenshaw’s offer. Rebuffed, Crenshaw & Co. sought alternative buyers in the private sector. In late July, the firm advertised they were “making a lot of GREY BLANKETS which we will be prepared to deliver in a few days.” They also dispatched samples of their products, including sending to Georgia “a piece of blanket which is very heavy and a handsome article.” The samples of Crenshaw’s work, reported a Georgia paper, “indicate a degree of perfection in woollen manufactures which we did not suppose to have reached here in the South.”11

An unnamed commercial firm viewed the sample blanket Crenshaw had made for the Quartermaster Department and offered to pay in cash $3.50 per blanket. Crenshaw agreed, but limited the contract to only 5,000 blankets, “being all the company chose to make for any one out of the army.” Based on the mill’s reported rate of production, this order likely took around three months to complete, making it almost certainly the same blanket described in the October 1861 Enquirer article. The astute businessman then resold the blankets, including likely at least some to the Quartermaster Department, for $7 a blanket.12

By August, the Crenshaw Woolen Company, having signed enough contracts with commercial firms to fully commit the mill’s production through January 1862, stopped taking further orders. The following month the firm sold in bulk all its remaining pre-war stock of fabric and blankets to a leading dry goods merchant. Crenshaw & Co.’s regular advertisement for “bed blankets,” which had reliably appeared in the Richmond papers since April, disappeared in October.13

After completing their existing contracts, including the order for 5,000 army blankets, the Crenshaw Woolen Company again contacted the Quartermaster Department, offering to contract with the government for the entire output of the mill. Again, the Quartermaster Department rejected the offer. The firm made the same offer to Virginia Governor Samuel Letcher, but he similarly declined, citing lack of legal authority to enter into the contract. Unable to secure government contracts, the Crenshaw Mill again turned to the private sector, selling its remaining stock at auction on January 8, 1862. The company then began selling sixty days’ worth of production at regular auctions. Finding that speculators were then reselling Crenshaw goods at exorbitant profits, the firm transitioned in late April to weekly auctions every Wednesday at noon.14

It is unclear how many of these auctions included blankets. Crenshaw & Co. advertised in early February 1862 the forthcoming sale of 1,000 Army blankets. Based on rates of production, this represents just over two months’ worth of the Mill’s output and may be all the blankets woven after Crenshaw completed its 5,000 blanket contract in fall 1861. Advertisements for Crenshaw’s auction sales, which ran until November 1862, made mention only of woolen cloth, which the firm offered in exclusively Indigo blue and grey.15

The Crenshaw Woolen Company finally obtained its first and only government contract in September 1862, agreeing to supply 20,000-25,000 yards of 54-inch width woolen cloth to the Quartermaster Department. The contract made no mention of blankets and surviving invoices confirm the firm began delivery of woolen cloth under this contract beginning in mid-October. These invoices document deliveries every 3-7 days of cloth but no blankets. The Crenshaw Company’s directors affirmed in late 1862 that this contract to supply cloth was the only contract the firm ever had with the Confederate government. While the Quartermaster Department may have purchased Crenshaw blankets at auction or from resellers and soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia likely privately purchased Crenshaw blankets from Richmond dry goods merchants, the Crenshaw Woolen Company was not the principal supplier of blankets it has previously been portrayed as.16

Success to Southern Manufactories – Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co

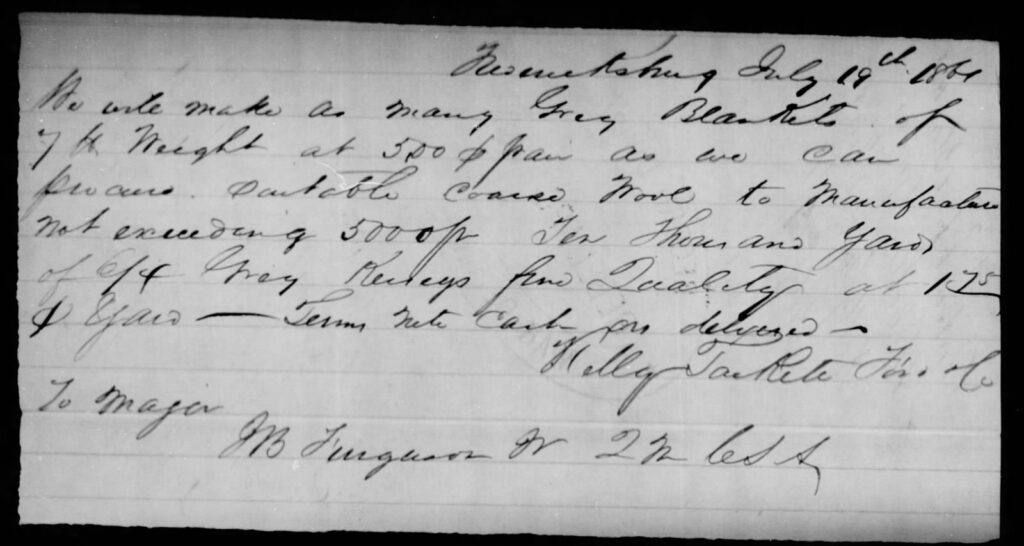

Crenshaw was not the only Virginia textile mill considered by the Quartermaster Department in summer 1861 as a potential source of army blankets. In July the Department signed a contract with Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. to produce up to 10,000 blankets. The blankets were not as heavy as those woven by Crenshaw, weighing only 3 ½ pounds, but they cost only $2.50 compared to Crenshaw’s quote of $3.25. Possibly due to the cost savings, the Quartermaster Department chose Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. over the Crenshaw Woolen Company as its major supplier of blankets.17

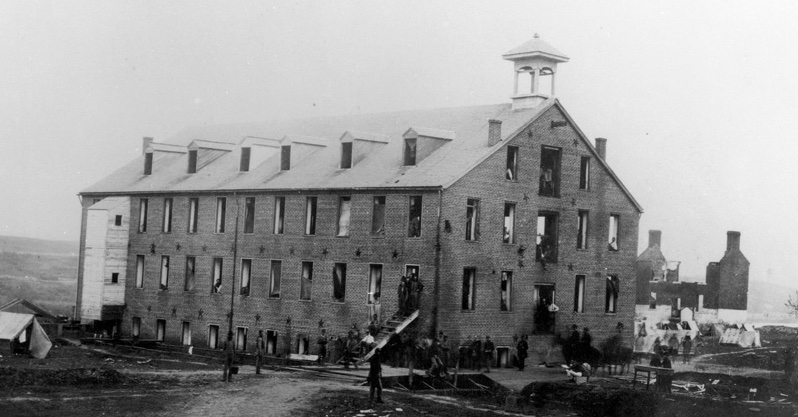

Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co., like Crenshaw, was established just prior to the war. In April 1859 the firm’s stockholders elected Granville Kelley as President and General Superintendent, with construction of the company’s Fredericksburg mill beginning in June. The brick structure, dubbed the Washington Woolen Mill, was 120 feet long by 60 feet wide and rose five stories. The Alexandria Gazette reported the arrival of the mill’s machinery in February 1860, proclaiming “Success to southern manufactories.” A May 1860 initial test of the machinery drew a large crowd of spectators.18

On the eve of war, the Washington Woolen Mill was operating nineteen broad looms capable of weaving 54-inch cloth and 18 looms to for 27-inch cloth. None of these looms were wide enough to produce the 60-inch blankets made by the Crenshaw Woolen Company, possibly meaning Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. blankets were pieced together from two narrower pieces of fabric sewn together along a central seam. The mill ran 1,000 spindles in four spinning machines, four sets of wool cards, three fulling mills, three presses for finishing cloth, and 22 bars for drying. It employed 35 women and at least as many men, with a monthly payroll of $1,000. The mill consumed around 800 pounds of wool per day and utilized cotton warps manufactured in neighboring Falmouth to produce 1,350 yards daily of primarily yellow and slate-colored kersey.19

Once the Washington Mill transitioned to wartime production, surviving invoices document the delivery of at least 5,848 blankets between June and October 1861. It is unclear whether documentation of further deliveries has been lost, or if Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. were unable to produce the full 10,000 blankets. In their initial contract proposal, they noted their ability to weave all of the promised blankets was contingent on them being able to secure adequate amounts of the coarse wool necessary for blankets. A single outlier invoice documents the delivery of seventy blankets on January 17, 1862.20

The advance of Union troops on Fredericksburg in spring 1862 threatened the firm’s operations. The firm dismantled as much of its machinery as possible and loaded it on eight old freight cars for evacuation south. In the confusion, however, the cars were left behind as Confederate troops retreated. An engine was rushed back up the rail line and retrieved the cars and their valuable machinery before they were captured by Union forces. The firm’s now vacant Washington Mill was seized by Federal authorities and converted for several months into a hospital, at which nurse Clara Barton observed her first amputation. During the 1864 Overland Campaign, the structure served as a hospital for the Union Fifth Corps.21

Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. used their rescued machinery to reestablish their operation in Manchester, just outside of Richmond. They once again became a significant supplier of woolen cloth for the Quartermaster Department, but none of the surviving invoices from this period mention blankets. It is unclear whether something about the relocation prevented the firm from producing blankets or perhaps the Confederacy’s dwindling wool supplies deprived the firm of enough coarse wool to resume blanket production. After the end of hostilities, Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. again packed up their machinery and returned to Fredericksburg in June 1865.22

Other Domestic Suppliers

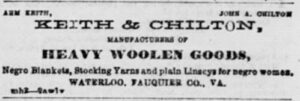

Kelly, Tackett, Ford, & Co. is the only domestic manufacturer known to have a significant contract to supply blankets to the Quartermaster Department for likely issuance to the Army of Northern Virginia. At least one other Virginia firm, Keith & Chilton, supplied limited amounts of blanket material to the war effort. Dr. John Augustine Chilton and Isham Keith operated a small mill in Waterloo, Virginia along the upper Rappahannock River in Fauquier County. This was a family enterprise, as Isham was married to John’s sister Juliet. Before the war, they advertised the production of heavy woolen goods, including “Negro Blankets, Stocking Yarns, and plain Linseys for negros.”23

Surviving invoices document the sale of at least 1,665 yards of “blanketing” to the Quartermaster Department in July and August 1861. The company has other invoices for 27-inch and 54-inch kersey cloth, suggesting that blankets produced from their “blanketing” were two narrower pieces of cloth sewn together as they likely lacked the broad looms found in the Crenshaw Mill. If true and depending on blanket length, their production would have only resulted in just over 400 blankets. The last surviving records for the company are from October 1862, as the advance of the Federal army in the area likely prevented further production. Isham died at age 62 in August 1863.24

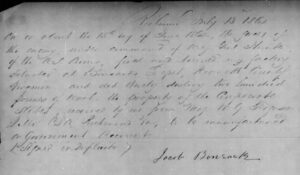

Prior research by notable Confederate material culture researcher David Burt has also highlighted Jacob Bonsack of Roanoke County, Virginia as a supplier of blankets to the Army of Northern Virginia, describing them of being made of coarse wool and jeans. The Bonsack family opened their woolen mill in 1822 and, while best known for their jean cloth, did produce blankets as well. Bonsack’s blankets earned praise at an 1843 exhibition:

“Specimens of Blankets, manufactured in Roanoke county, at the manufactory of Mr. J. Bonsack, excited general admiration. Indeed, we never saw so good, and we hear dealers in dry goods say, they never saw better from any quarter. Mr. Bonsack has a woollen [sic] manufactory, and, regarding these Blankets as specimens of this work, well does he merit the public encouragement. He reflects high credit upon the manufacturing reputation of our State. Had a premium been offered for such fabrics, it would certainly have been awarded to Mr. Bonsack.”25

Surviving records of Bonsack’s business dealings with the Confederacy, however, contain no indications he contributed blankets to the war effort. Instead, the firm wove large amounts of jean cloth for the Confederate Quartermaster Department. A May 1863 contract proposal to supply jean cloth noted that “the whole capacity of my factory to be employed in the production of the govt. until completed.” When Federal raiders passed through Roanoke County in June 1864, a Union officer demanded Bonsack cease providing fabric to the Confederate Army. Bonsack reportedly refused and his mill was burned to the ground. The mill held some 200 pounds of wool belonging to the Confederate Quartermaster’s Department at the time of its destruction.26

While other eastern states had sizable textile industries, research to date has been unable to locate additional domestic blanket suppliers from this region. Virginia contained most of the South’s antebellum woolen production, with 45 mills in 1860. Georgia was next with 11 mills producing woolen cloth, followed by North Carolina with seven and Alabama with six mills. The majority of the south’s textile mills produced exclusively cotton fabric. As of November 1861, the Athens Southern Watchman reported Georgia produced 473,500 yards of cotton goods per week, but only 23,000 yards of woolen kerseys and linseys and 22,900 yards of wool and cotton blend jeans and cassimeres. Review of surviving business records of major North Carolina and Georgia textile mills, such as Georgia’s Athens Manufacturing Company or the Eagle Manufacturing Company and North Carolina’s Young, Winston & Orr, F & H Fries, Mountain Island Factory, Yadkin Manufacturing Company, or Blount Creek Manufacturing Company, found no invoices or contracts involving blankets.27

With limited ability to produce blankets, the growing Confederate military rapidly consumed existing commercial stocks, buying up business’ pre-war holdings of British and Northern-made blankets. Within days of Virginia’s secession, Petersburg-based import and dry goods firm Hamilton & Graham sold at least 550 blankets to the Confederate government. Dry goods wholesaler Brown, Tate & Co. of Charlotte, North Carolina sold 30 extra heavy blankets to the Mecklenburg County Flying Artillery and another 58 gray blankets to the military. In South Carolina, the Rutherford Volunteers purchased four blue Mackinaw blankets and 110 duffel blankets from Chamberlain Miler & Co. The firm also shipped blankets to Richmond in June 1861 and in July paid for damages to several bales of blankets.28

That or Nothing – Early Importation

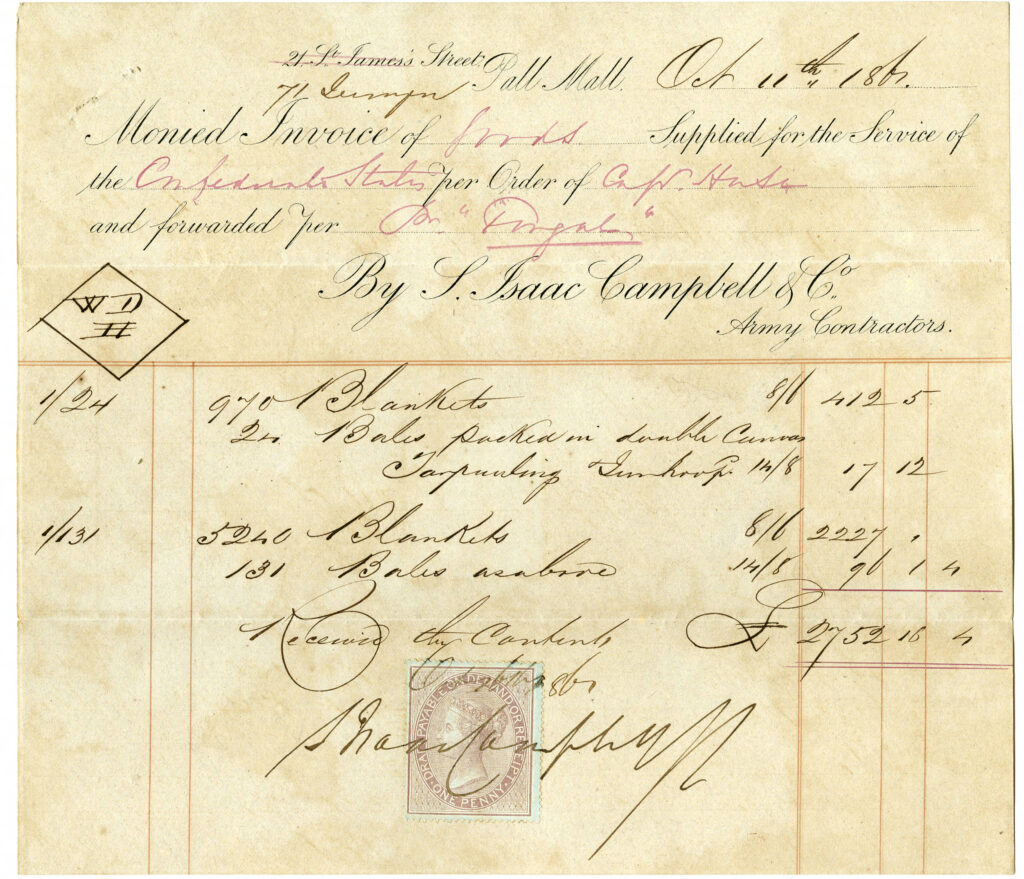

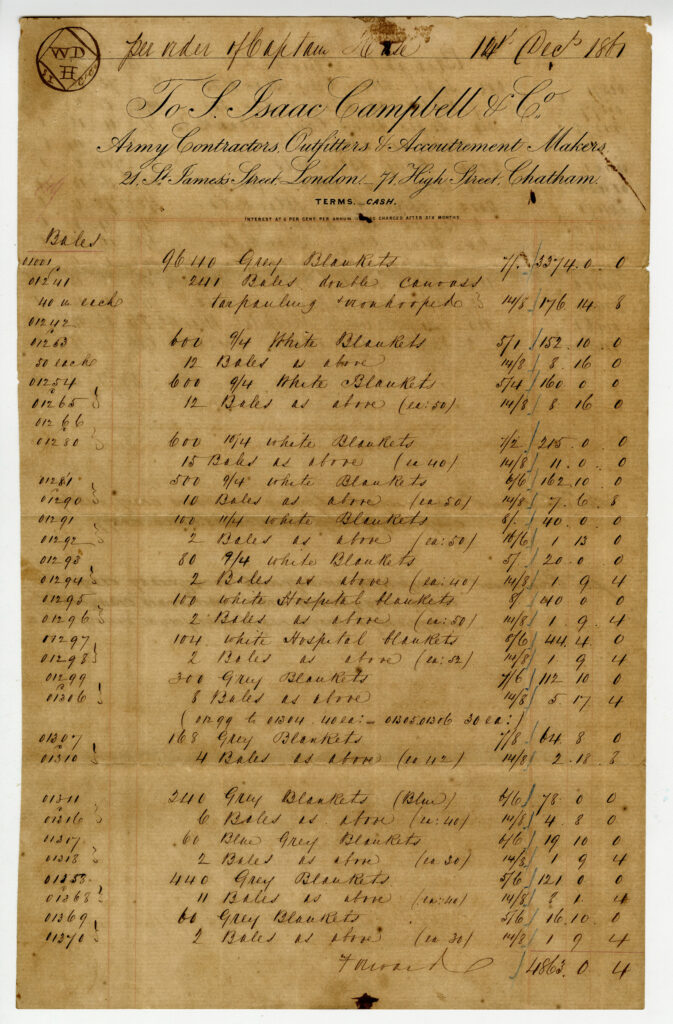

With Myers’ May 1861 request to send a purchasing agent abroad remaining unaddressed, domestic production and antebellum stocks were supplemented by blankets imported into the Confederacy by Ordnance Bureau agent Caleb Huse and private enterprise. On June 17, 1861, Huse and his superior officer Major Edward Anderson first visited the offices of S. Issac Campbell & Co., the firm that would, for a time, become the Confederacy’s almost exclusive supplier in England. Within weeks, contracts with S. Isaac Campbell & Co and several other British firms had begun filling warehouses with supplies desperately needed by southern armies. While material was relatively easily acquired in England, Huse and Anderson faced difficulty shipping their purchases to the Confederacy. The Union declaration of a blockade and a British royal proclamation asking British subjects to respect a lawfully constituted blockade had cut off all regular trade into the South.29

On July 29, Fraser, Trenholm & Co. approached Huse and Anderson with a potential solution to their shipment problem. The firm, the Liverpool arm of the prominent Charleston commercial house John Fraser & Co., was serving as Huse and Anderson’s financial agents in England. The firm was, for its own commercial interests, preparing a ship, Bermuda, to run the blockade and offered space in the ship’s hole to the Confederacy. The offer, however, was no act of charity. “The rates they charged were high,” wrote Anderson in his diary, “but it was that or nothing.”30

The Bermuda arrived safely in Savannah on September 16, 1861. While the ship carried some government cargo purchased by Huse and Anderson, the majority was consigned to Fraser, Trenholm & Co. for “private speculation.” Most of Fraser, Trenholm & Co.’s cargo of some 20,000 blankets, 60,000 pairs of army shoes, 6,500 Enfield rifles, rifled artillery, medical supplies, and large quantities of ammunition were sold to the Confederate government and private merchants at high prices, netting John Fraser and his partners tremendous profits. The ship would make a second attempt to run the blockade in March 1862, but was captured in the Bahamas by the USS Mercedita.31

The privately-owned Thomas Watson, a former illegal slave ship that had operated out of New York in 1859 and 1860, had left Wilmington in late June and sailed for Liverpool. The vessel departed England in August laden with “blue, red, and gray flannels, gray and blue blankets, machinery, salt, etc.” On October 12, Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles alerted the Atlantic Blockading Squadron of a “shipment from England to Halifax of large quantities of blankets, etc. intended… for the blockaded ports.” When the Thomas Watson attempted to enter Charleston harbor three days later, Federal cruisers gave chase. Attempting to outrun the pursuers, the ship instead ran aground on a reef and had to be abandoned and burned. One of the Federal pursuers, the USS Flag, recovered part of the Thomas Watson’s cargo from the wreck, including four bundles of gray blankets.32

Back in England, Huse and Anderson continued, in addition to the munitions they had been tasked to purchase, to also purchase quartermaster stores. They also encountered other Confederate agents of varying degrees of credibility. Anderson noted in his diary a meeting in Liverpool with Edward Gautherin, who claimed to be an authorized Confederate government agent to purchase blankets but lacked funds. “Of course I could not entertain any request from him to furnish means” wrote Anderson, “nor do I intend to mix myself with these stray ways and drift along from Richmond. Huse & I can purchase all that is wanted.” Gautherin, of Gautherin & Girard of Paris, would in early 1863 go on to sign a contract to supply the Confederate Navy two years’ worth of blankets, shoes, and cloth and would become one of the Navy Department’s most trusted overseas suppliers.33

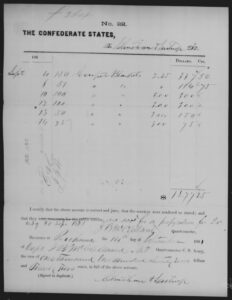

Anderson and Huse, meanwhile, could readily purchase, but still lacked the means to ship their purchases. In late August 1861, the Confederate Congress authorized $1 million to purchase blankets, woolen clothing, shoes, leather, and flannel, as well as a ship on which to ship them. Working with the Confederate naval agent in England, Huse and Anderson purchased for the Confederacy the Fingal. Unlike the Bermuda, where government material shared space with commercial cargo, the Fingal would be entirely devoted to government purchases. The ship departed England on October 10 with Anderson aboard and safely reached Savannah on November 12, 1861. Included in the ship’s cargo hole were 6,210 blankets (9,982 yards) purchased from S. Isaac Campbell & Co., as well as 11,340 rifles, 7 tons of shells, 230 swords, 499,000 cartridges, 24,100 pounds of gunpowder, 500 sabers, clothing, medicine, pistols, and leather. A Confederate newspaper heralded the arrival of the Fingal, claiming it was loaded with blankets and army stores sufficient for four brigades. The Confederate quartermaster in Savannah dispatched 155 bales of blankets north to Richmond on November 26, almost certainly the blankets brought in by the Fingal.34

With Anderson gone, Huse appears to have felt empowered to further exceed his orders and purchase increasing amounts of quartermaster stores beyond the ordnance stores that he had been tasked to procure. He prepared an even large shipment of items purchased from S. Isaac Campbell & Co., to be shipped on the single screw iron hull steamer Gladiator. Among the items in the huge ship’s hole were 5,055 pairs of gray blankets, 250 white blankets, and 2,200 blankets of unspecified color.35

The large and slow Gladiator, prevented from leaving Nassau harbor by a watchful Union gunboat, transshipped its cargo to several smaller, faster vessels. On January 30, 1862 Confederate commercial agent Lewis Heyliger dispatched the Kate at New Smyrna, Florida with 32 bales of “blankets and serge” from the Gladiator, along with 6,000 Enfield rifles, powder, cartridges, caps, medical supplies, and mess tins. Additional cargo from the Gladiator landed on March 2, 1862 aboard the Cecile.36

Not all the cargo purchased by Huse had fit on the Gladiator. The Sidney Hall left the mouth of the Thames in early November carrying the remainder of the Gladiator’s intended cargo. The American Consul in London informed Washington that the Sidney Hall had a “large quantity of blankets, army cloths, saltpeter, etc.” He also reported the ongoing loading of the Stephen Hart.37

Huse had been preparing the cargo of the American-built schooner Stephen Hart simultaneous to the preparations for Gladiator. He purchased from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. 1,354 pairs of “super russet blankets,” 1,710 pairs of white blankets, and 6,805 gray blankets. “Super” referred to the blanket’s grade, indicating a higher-grade quality of blanket, above fine and below super super. The Stephen Hart, partially owned by Fraser, Trenholm & Co., left Liverpool in mid-November but was captured on January 29, 1862 off the coast of southern Florida. Upon inspection by a New York prize court, the Stephen Hart was found to carry 6,800 gray blankets, each weighting 4 ¾ pounds, 1,600 white blankets weighting 5 pounds, and 150 white blankets weighting 5 ¼ pounds. The entire cargo, which also included small arms, artillery, ammunition, accouterments, knapsacks, and other war material, was claimed by S. Isaac Campbell & Co as their own and they tried unsuccessfully to regain the cargo via legal means.38

Undeterred by the capture of the Stephen Hart, Huse prepared his largest shipment of blankets to date. December 1861 and January 1862 invoices detail the quantity, color, and, in some instances, the size of 18,097 blankets purchased by Huse from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. and shipped via the Economist and the Southwick. The following is a consolidated list of these invoices. A small number of entries also specified that they were super grade, but these were too few to be separately specified.

- 13,648 pairs of gray blankets of unspecified size

- 960 pairs of blankets of unspecified color and size

- 404 pairs of white blankets, hospital size (72 inches wide)

- 1,780 pairs of white blankets, size 9/4 (81 inches wide)

- 605 pairs of blue gray blankets of unspecified size

- 600 pairs of white blankets, size 10/4 (90 inches wide)

- 100 pairs of white blankets, size 11/4 (99 inches wide)39

The Economist, owned by the ever-present Fraser, Trenholm & Co., arrived safely in Charleston on March 14, 1862 after passing through Bermuda. The Southwick arrived in Nassau in early April and offloaded its cargo of blankets and other supplies for transshipment via smaller vessels.40

Meanwhile, Fraser, Trenholm & Co. were building on the success of the Bermuda and preparing additional ships for their own commercial shipments, in addition to those conducted with Huse. The firm’s Charleston packet Cheshire had run out past the blockade and arrived in Liverpool in September. It departed England on October 10, 1861, bound for Nassau. Soon after its departure, the American Vice Consul in Liverpool alerted his government that “I am informed that large orders for blankets for the south are being executed in Yorkshire. You would observe by the manifest of the Cheshire and Eliza Bonsall that bales of blankets formed part of both cargos.” The Eliza Bonsall was also owned by Fraser, Trenholm & Co. Both ships had bales marked <W. B. & Co>; a third ship, the Consul, was set to sail from England in early December with a cargo of salt and blankets and had bales with the same marking, warned the American diplomat. After Cheshire safely arrived in the South, Savannah businessman G. B. Lamar contacted the Confederate War Department on December 2, 1861 offering to sell 60 bales and two packets of blankets from the vessel.41

The arrival of a commercial cargo in Charleston in early January 1862 elicited significant excitement. “Yesterday one of our city wharves presented quite an active scene,” wrote a local newspaper, “in consequence of a fine display of merchandise which crowded the surrounding space and which was being discharged from a vessel lately from a foreign port. The cargo consisted of English blankets, Confederate gray cloths, hardware in casks, coffee, soap, candles, codfish, spool cotton, English paper and envelopes, butter, arrowroot, cheese, linens, hosiery, buttons, needles, Spanish cigars, and various other items of great value at this time.” While the name of the ship was omitted, it may have been the Ella Warley, another ship owned by Fraser, Trenholm & Co. and which delivered a cargo into Charleston on January 3 that included at least 12,300 blankets.42

The substantial profits being earned by Fraser, Trenholm & Co. by importing desperately needed items like blankets did not go unnoticed by other entrepreneurs. As early as August 1861, a British ship had been forced by weather to land in Rhode Island. One of the passengers was a French citizen named Louis de Bebian, employed by the Wilmington firm O. G. Parsely & Co. Among his papers Federal authorities found instructions from the company for de Bebian to proceed to Liverpool and there to purchase army blankets, coffee, clothing, and iron for shipment to Wilmington.43

Another Wilmington company, J. & D. MacRae & Co. noted in November that “blankets, shoes, gray cloths, and cassimers, pig and hoop iron, kersey and military stores, block tin, etc. all very scarce and command extreme prices. We would like a joint interest in a shipment including any of the above articles.”44

Other companies sought to more directly copy Fraser, Trenholm & Co. and commission cargo ships to run into Southern ports, but met with mixed success. The USS Dale captured, on November 15, 1861, the British schooner Mabel with a cargo that included seven bales of blankets, as well as cloth, saddles, tin, lead, coffee, potatoes, shoes, revolvers, and swords. The vessel claimed to be sailing from Havana to New York, but carried paperwork indicating she had had departed Nassau and was seized attempting to approach Savannah. The USS Bienville chased ashore a schooner along the southern Georgia coast on December 15 and burned it along with its cargo blankets, shoes, coffee, cigars, and other material.45

Another entrant in the industry, Zachariah C. Pearson, mistakenly bought a number of large, deep-laden vessels which carried large amounts of valuable cargo but were too slow to outrun blockade runners. His ship Patras was captured in April 1862 trying to enter Charleston loaded with powder, arms, quinine, and coffee. Modern Greece was lost after beaching itself outside of Wilmington in April 1862 and Ann was captured in May 1862 trying to enter Mobile. For all three vessels, this was their first and final attempt to run the blockade.46

Meanwhile, as importers grew rich, the dwindling availability and rising cost of blankets and other goods drove some antebellum companies out of business. Richmond dry goods merchant Watkins & Ficklin, one of the original two merchants to sell Crenshaw Woolen Company blankets in 1860, were forced out of business and liquidated their remaining stock in a November 19, 1861 auction. Items for sale included “White, Gray, Blue and Green, English, Army and Bed blankets.”47

Prevent Our Brave Defenders from Suffering – Charity Donations

The increased flow of imported blankets was supplemented by private donations. A group of concerned citizens in Tennessee wrote in July 1861 to Secretary of War Walker asking; “Can the [War] Department furnish all our soldiers with socks, shoes, coats, blankets, and shirts, and every other article necessary to constitute a solders winter dress?” “If Richmond was unable to provide for the soldiers” the citizens inquired “whether the Government wanted aid and cooperation in the [manner]?” If so, they suggested the War Department publicize a plan to coordinate civilian donation efforts.48

Walker immediately wrote to the state governors, requesting their assistance gathering woolen clothing and blankets from the civilian population for benefit of the military. “[You are] doubtless aware of the difficulty of procuring a full provision in consequence of the blockading of our ports, and the limited quantity of goods in the market place.”49

A few weeks later, on August 31, 1861, the Confederate Congress passed a law requiring the Secretary of War to “make all arrangements for the reception and forwarding of clothes, blankets, and other articles of necessity that may be sent to the Army by private contributions. Walker delegated this responsibility to Myers. In the following months, each state was directed to appoint local and state-level chairmen to solicit and collect donations. These agents were required to forward to their proper destination contributions from various citizens and county associations. Donations of blankets, clothing, and shoes for general distribution to the army were to be paid for in Confederate bonds. The Central Committee of Tennessee published a notice that “if any blankets can be furnished by any person they will be thankfully received of any kind and color.”50

In Georgia, Governor Joseph Brown issued an impassioned plea for donations in support of Georgia’s sons in Virginia; “They are our fellow citizens, our neighbors, our friends. They are enduring all the toils and labors of a soldier’s life… Winter will soon be upon us, and it will be impossible for them to get…such supplies of clothing, shoes, and blankets, as are absolutely necessary in that severe climate for their health and comforts. Shall we permit them to suffer for the necessities, while we have plenty at home? NEVER!…. I wish to purchase… all the good blankets that can be found in the market.”51

The response from Confederate civilians was overwhelming. “Never was there such a patriotic people as ours!” wrote a War Department clerk. “Their blood and their wealth are laid upon the altar of their country… contributions of clothing, provisions, etc., are coming in large quantities, sometimes in the amount of $20,000 in a single day.” By November, a soldier in Richmond reported “… clothing for the winter campaign is abundantly supplied. True much of it is the result of private contribution, but this speaks the more for the patriotism of the people.”52

Among the donations sought by Confederate authorities was an expedient, emergency solution to the increasing scarcity of blankets. As early as September 1861, the Confederate military began repurposing flat ingrain wool carpets as makeshift blankets. The Richmond firm Christian & Lathrop that month sold 595 “carpet blankets” to the Confederate Quartermaster Department. Additional purchases of blankets from the firm occurred in November. Also in September, James G. Bailie & Brother, Dealers in Carpetings, Rugs, Oil Cloths, Mattings, and Linens in Augusta, Georgia, sold Confederate authorities 1,482 carpet blankets.Although outside of this study’s focus on the Army of Northern Virginia, the Quartermaster Depot in Nashville reported in January 1862 having used 20, yards of carpeting for emergency blankets. They contracted with J.T. Lord to purchase 13,041 lined carpet blankets between December 1861 and February 1862.53

Carpets remained in use as blanket substitutes beyond the first winter of the war. The Central Association for the Relief of the Soldiers of South Carolina called in fall 1862 for the donation of woolen carpets to be turned into blankets. In 1861 and 1862, the North Carolina Quartermaster Department issued at least 11,952 carpet blankets, exhausting the supply of carpets in the state by fall 1862. Some of these carpet blankets were issued to the Thirty-Fifth North Carolina, of Ransom’s Brigade, on November 15, 1862 and they continued to be issued prior to the Gettysburg campaign. An 1863 entry for the Confederate depot in Atlanta stated 20,559 yards of carpeting were in storage for making blankets.54

At the start of the war’s second year, the Confederacy was obtaining blankets in several ways. The Quartermaster Department had directly contracted with firms like Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. to produce blankets for the military and had solicited blanket donations from the civilian population. Purchasing agents bought up dwindling antebellum blanket and carpet supplies and bid to purchase blankets imported from abroad by private speculators like Fraser, Trenholm & Co. The Confederate government also signed optimistically large contracts for firms to purchase and import blankets to sell to the government at a predetermined rate, but little had come of these. Finally, Caleb Huse, despite no orders to do so, continued to purchase quartermaster stores in England and arrange shipment to Bermuda and the Bahamas. Once in the islands, Confederate agents transshipped the goods onto commercial vessels willing to make the run into southern ports in exchange for extremely high freight charges.55

While perhaps disorganized and inefficient, the combination of purchases by Huse, importation by private business, domestic production, public donations, and conversion of carpets initially succeeded in providing an adequate supply of blankets for the first winter of the war. The Quartermaster Department issued 27,747 blankets to the army in Virginia between October 1861 and March 1862. While this not nearly enough for a field force that numbered circa 80,000 at the time, it was supplemented from donations and other non-official sources. By mid-winter, a Congressional investigation of the Quartermaster Department reported that supplies, shoes, and blankets “are on hand or have been distributed in sufficient quantities as, with the contributions of states and individuals, to place our troops beyond the danger of suffering during the present winter.”56

Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin, who replaced Walker in September 1861, reported in February 1862 that necessary supplies that winter “could not possibly have been furnished in time for the wants of the present winter had not the entire population aided with common accord the efforts of the Government to prevent our brave defenders from suffering for want of needful protection from exposure.” Additionally, large amounts of blankets, medicine, and equipment had arrived via importation. “It will hereafter be in the power of the Department to furnish all that is required,” he boldly predicted, “not only from supplies of blankets, cloth, and shoes already imported from Europe, but from the productions of manufacturing establishments at home.”57

Go to Chapter Two

Footnotes

- Craig L. Barry and David C. Burt, Suppliers to the Confederacy III: British and European Imported Quartermaster Goods, Artillery and Other Ordnance (St. Petersburg, FL: BookLocker.com, 2017), p. 276.

- Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, (Washington: War Records Office, 1900), p. 314.

- Richard D. Goff, Confederate Supply (Durham, N.C: Duke University Press, 1969), p. 16 and 34.

- Frederick J. Glover, “Thomas Cook and the American Blanket Trade in the Nineteenth Century,” Business History Review, 35, no. 2 (1961), p. 230 and 232.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 234-235; Frederick J. Glover, “Dewsbury Mills: A History of Messrs. Wormalds and Walker Ltd., Blanket Manufacturers, of Dewsbury” (PhD dissertation, University of Leeds, 1959), p. 625; Leone Levi, ed., Annals of British Legislation: Being a Classified and Analysed Summary of Public Bills, Statutes, Accounts and Papers, Reports of Committees and of Commissioners, and of Sessional Papers Generally, of the Houses of Lords and Commons, vol. VIII (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1861), p. 103; United States Census Office, Manufactures of the United States in 1860, Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865), p. xxii; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), January 23, 1861.

- Manufactures of the United States, p. xxiii and xxv; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), October 1, 1861.

- The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), August 14, 1860; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 1, 1860; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 21, 1860.

- The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), December 04, 1860; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), October 01, 1861.

- See David C. Burt, “ACWS Archives – ANV Blankets and Substitutes,” The American Civil War Society (UK), August 2003, https://acws.co.uk/archives-military-anvblankets, and Harold S. Wilson, Confederate Industry: Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2002); Richmond Enquirer, October 17, 1861.

- Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1862.

- The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), July 26, 1861; Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel, July 18, 1861, quoted in Vicki Betts, “Textile Factories in the South: Articles from Civil War Newspapers,” Special Topics-Civil War Newspapers, Paper 26 (Tyler, TX: University of Texas at Tyler, 2016).

- Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1862.

- The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), October 1, 1861; Richmond Enquirer, December 24, 1861.

- Richmond Enquirer, December 24, 1861; Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1862; Daily Richmond Whig, May 08, 1862.

- The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), February 05, 1862; Daily Richmond Whig, May 08, 1862; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 15, 1862.

- Crenshaw and Co, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Crenshaw and Woolen Company, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1862.

- Kelly, Tackett Ford and Co., Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Alexandria Gazette, April 25, 1859; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), June 14, 1859; Alexandria Gazette, February 16, 1860; Alexandria Gazette, May 14, 1860; John Henessy, “A Vivid Image of an 1864 Hospital–The Washington Woolen Mill,” Mysteries & Conundrums – Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, 12 August 2010, https://npsfrsp.wordpress.com/2010/08/12/a-vivid-image-of-an-1864-hospital-the-washington-woolen-mill/.

- Henessy.

- Kelly, Tackett Ford and Co. Citizens File.

- Daily Richmond Whig, April 19, 1862; Alexandria Gazette, June 17, 1862; Henessy.

- For an excellent examination of Kelly, Tackett, Ford, & Co’s contracts for woolen cloth production, see Dick Milstead, “When is ‘Kersey’ Not Kersey? Textile Transactions Between the Richmond Clothing Bureau and Kelly, Tackett, Ford, & Company,” Liberty Rifles, https://www.libertyrifles.org/research/uniforms-equipment/kersey; Kelly, Tackett Ford and Co. Citizens File; Alexandria Gazette, May 31, 1865.

- “Juliet Keith,” Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/62994935/juliet_keith; “John Augustin Chilton,” Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/21418587/john_augustine_chilton; “Isham Keith,” Find A Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/62994918/isham_keith; Richmond Daily Whig, December 28, 1860.

- Keath and Chilton, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; “Isham Keith,” Find A Grave.

- Burt, Blankets & Substitutes; Frazier Associates, Historical Architecture Reconnaissance Survey Report – Roanoke County (1992), p. 76; Richmond Enquirer, November 7, 1843.

- Jacob Bonsack, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Goodridge Wilson, “The Southwest Corner,” Roanoke Times, https://hswv.pastperfectonline.com/archive/3A4ED096-05C9-45BB-B893-841397330004.

- Manufactures of the United States, p. xxv; Athens Southern Watchman, November 13, 1861, quoted in Betts; Athens Manf’g Company, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.;Eagle Manufacturing Company, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Young Winston and Orr, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Fries F and H, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Tate, Thomas R, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Yadkin Manufacturing Company, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Blount Creek Manufacturing Co. , Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Hamilton and Graham, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Brown, Tate and Co., Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Chamberlain Miler And Co., Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- W. Stanley Hoole, ed., Confederate Foreign Agent: The European Diary of Major Edward C. Anderson (Atlanta, GA: Confederate Publishing Company, 1976), p. 23; Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1988), p. 50.

- Hoole, p. 37; Wise, p. 50.

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Ser. I, Vol. 6 (Washington: War Records Office, 1897), p. 279; Wise, p. 51; Joseph McKenna, British Blockade Runners in the American Civil War (Jefferson, NC: MacFarland & Company, Inc., 2019), p. 15.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 6, p. 314, 323-324 and 327-328; Clifford Browder, “New York and the Slave Trade,” No Place For Normal: New York, 2014, https://cbrowder.blogspot.com/2014/01/110-new-york-and-slave-trade.html.

- Hoole, p. 55; Official Records of the Navies, Ser. II, Vol. 2, p. 555-556 and 644.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p. 584; Colin J. McRae Papers, Huse Audit Series, South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum; Memphis Daily Appeal, November 19, 1861; McKenna, p. 21; C. L. Webster, Entrepôt: Government Imports into the Confederate States (Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press, 2010), p. 50-51.

- McRae Papers.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p. 895; Correspondence Concerning Claims against Great Britain, Vol. VI (Washington: Government Printing Officer, 1871), p. 58-59; Craig L. Barry and David C. Burt, Suppliers to the Confederacy Vol. II: S Isaac Campbell & Co., London, Peter Tait & Co., Limerick (Fairfield, OH: The Stainless Banner Publications, 2014), p. 49.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 6, p.461.

- McRae Papers; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 597; “Claim No. 442,” Mixed Commission on British and American Claims, Vol. XXXII (1873), p. 182; The Springbok (U.S. Supreme Court, 1866); Webster, p. 37-38.

- McRae Papers.

- Wise, p. 65 and 251; Webster, p. 39.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 6, p. 47, 200, 368, 462, 510, and 661; Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p. 770.

- Memphis Daily Appeal, 11 January 11; Webster, p. 149.

- John Bassett Moore, History and Digest of the International Arbitrations to which the United States Has Been a Party, Vol IV (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898), p. 3316-3317.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 6, p. 468.

- Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 12, p. 345-346 and 402.

- McKenna, p. 16.

- Staunton Spectator, November 19, 1861.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p. 506.

- Ibid, p. 534.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p. 595 and 601; Thomas M. Arliskas,Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown: Notes on Confederate Uniforms (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2006), p. 19-20.

- Daily Enquirer (Columbus, GA), September 10, 1861.

- John B. Jones,A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States’ Capital, Vol. I (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co, 1866), p. 84; San Antonio Weekly Herald, November 9, 1861.

- Christian and Lathrop, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Ballie, James G, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Webster, p. 55; Lord, J T, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Central Association for the Relief of the Soldiers of South Carolina: The Plan, and Address, Adopted by the Citizens of Columbia, October 20, 1862 (Charleston: Evans and Cogswell, 1862), p. 14; “Doc No. 1,” Documents Accompanying the Governor’s Message, Adjutant General’s Report, Dated 15 Nov 1862 (Raleigh: W.W. Holden, 1862); Burt, Blankets & Substitutes; Arliskas, p. 75.

- Goff, p. 43.

- Wilson, p. 28; OR ser.4:v.1:Section 2, p. 884.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 1, p. 884, 958-959.