This is Chapter Three of a four chapter article. See Chapter One, Chapter Two, and Chapter Four. For a brief summary of this article, adapted to address the needs of living historians, see Blankets for Your Confederate Impression published in the ‘Living History Gazette.’

Every Exertion has Been Made – Spring 1862

With such a robust British blanket industry from which to draw, in the spring of 1862 Huse continued work with Fraser, Trenholm & Co. to arrange shipments of blankets alongside ordnance stores. The newly built English steamer Economist No. 2 sailed to Hamburg to take onboard 80 artillery pieces, but returned to England in late February 1862 to take on blankets and other cargo before sailing for Nassau. American diplomats in England reported in March the loading of at least three ships, the Minna, the Mary, and the Pacific, with cargos of blankets as well as small arms, artillery, powder, swords, knapsacks, clothing, shoes, raw materials, and other supplies intended for the Confederacy. At least one of these, the Minna, was owned by Fraser, Trenholm & Co.1

With Lewis Heyliger’s assistance, the Thomas L. Wragg was prepared to sail on April 5 from Nassau with bales of blankets and other cargo primarily owned by John Fraser & Co. It arrived in Wilmington on April 24 carrying bales of grey and white blankets. On May 11 the Memphis left Liverpool with 12,000 woolen blankets, 45 tons of gunpowder and large amounts of cartridges, lead shot, and steel. The U.S. Consul in London informed the Federal government on May 16 that the Melita was 30 miles below London loading 450 barrels of gunpowder. The ship had already been loaded with blankets, over 15,000 Enfield rifles, artillery pieces, army cloth, saltpeter, and other material. Owned by S. Isaac Campbell & Co., the Melita had been chartered by Fraser, Trenholm & Co. for the voyage. It successfully ran the blockade multiple times before being retired in May 1863.2

Fraser, Trenholm & Co. continued throughout the summer to dispatch ships carrying blankets and other goods, both on government account and for commercial resale. Their ship Minho arrived in Charleston on June 4 with 22 bales of blankets abroad, while the Herald landed early the following month carrying 108 bales.3

This steady stream of imports joined British blankets imported prior to the war and now in use by Confederate soldiers. An officer of the Fortieth Virginia Infantry reported the loss of his horse near Gaines’ Mill on June 27, noting that “Strapped behind the saddle was a pair of white English blankets.” In July, a private in the Thirty-Fourth North Carolina Infantry sent home from Richmond an “inglish blanket” he had recovered from the battlefield, describing it as “one side black and the other read [sic; red].”4

Despite the successful shipments, Secretary Benjamin’s rosy predictions earlier in the year that domestic production and foreign imports could fully supply the army were proving increasingly dim. Myers scoured local markets to purchase all available blankets in the spring and borrowed surplus blankets from the Confederate Navy. By July, a quartermaster official informed Benjamin’s replacement as Secretary, George W. Randolph, that “to obtain a full supply of clothing for the Army is becoming more embarrassing and difficult as the raw material is diminishing and the machinery employed in its manufacture becomes worn out. Every exertion has been made to render all the resource of the country available, but if… there were ample supplies of the raw material the capacity to manufacture them is wanting, thereby rendering it certain that a reliance upon our own sources of supply will be in vain.” Alternatively, he argued “The government would save largely by purchasing abroad, even if one of every three cargoes were lost.” The Quartermaster Department’s reliance on private importation had proven unreliable and transferred enormous profits to importers. The Quartermaster Department, he argued, should instead adopt the practice of the Ordnance Department and dispatch a suitable procurement agent abroad to purchase less expensive supplies on the European market. The Quartermaster Bureau recommended Major James Boswell Ferguson Jr.5

Ferguson was the perfect candidate for the job. Unlike Huse, a pre-war soldier and educator, Ferguson had over twenty years of business experience. He had obtained extensive knowledge of the British textile industry and knew many mill owns personally, having previously operated his own import and export firm, J.B. Ferguson Jr., Bros. & Co. Myers had initially proposed sending Ferguson to England as a quartermaster agent in October 1861, but the Secretary of War at the time, Benjamin, rejected the proposal of directly purchasing quartermaster supplies in Europe in favor of continued reliance on contracts with commercial parties. Now, with a new secretary in place, Myers finally got his approval to dispatch Ferguson. It would, however, be months before Ferguson could reach England and months more before any purchases he made would arrive on Southern shores. In the meantime, the weather was slowly getting colder as summer turned to fall.6

So Greatly Needed at Home – Fall 1862

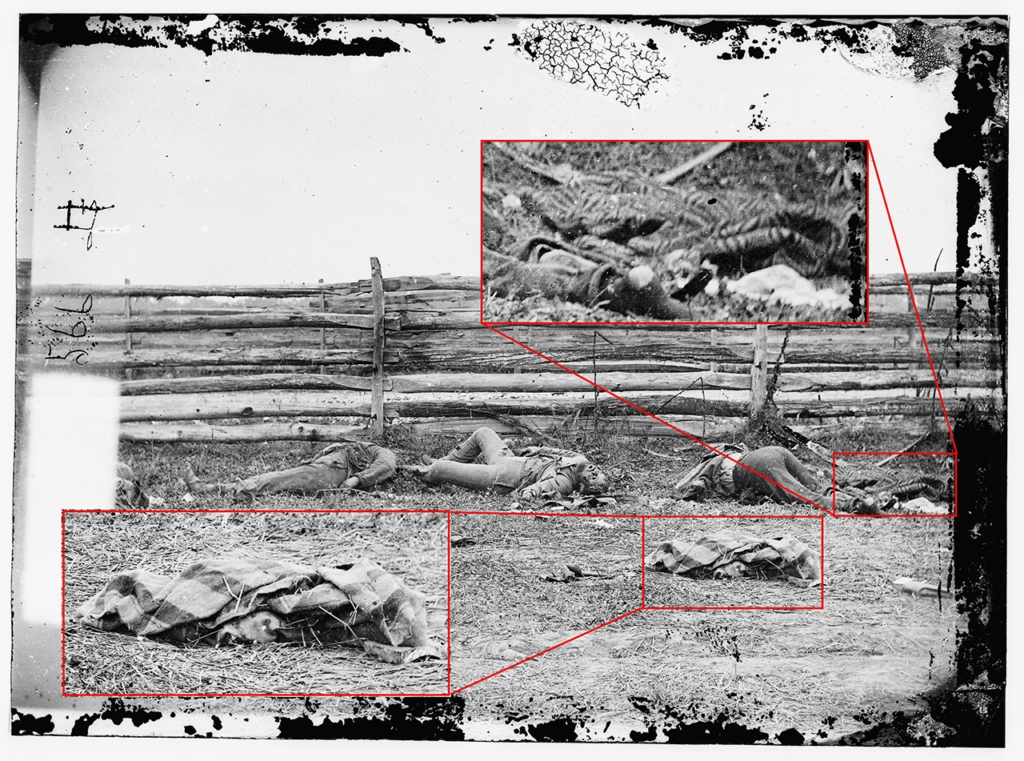

Alexander Gardner’s photographs of the Confederate dead at Antietam provide a tiny glimpse into the blankets of the Army of Northern Virginia by this point in the war. A photograph of Confederate casualties along the Hagerstown Pike, possibly members of John R. Jones’ Division, shows two blankets. The first, in the foreground and more clearly seen, is light in color with wide stripes of at least three different colors. A narrow header bar stripe is visible at each end. This civilian style blanket may have been donated, brought from home by the soldier, or imported by a commercial firm. The same photo also contains a dark colored patterned cotton coverlet along the right edge of the image. This was likely a donation or from the soldier’s family. Either blanket could also have been a recent acquisition, obtained during the march through Maryland.7

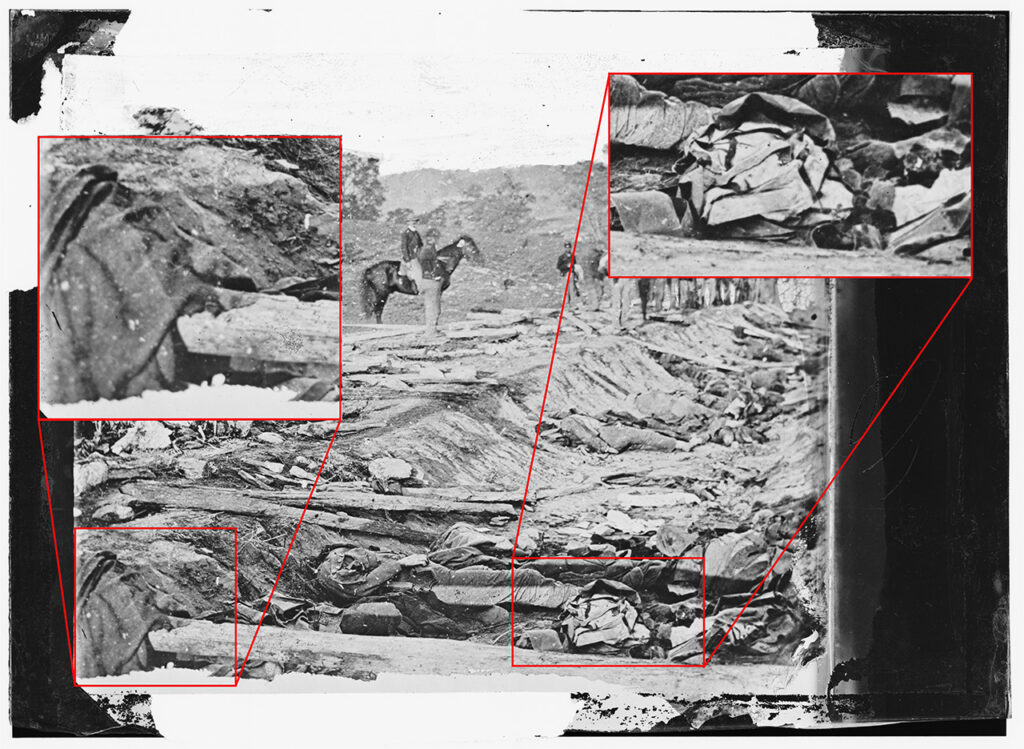

A second image, showing fatalities in Bloody Lane, also contains two blankets. The more visible of the two, on the left edge of the shot, is medium colored, perhaps grey or brown. It has a single wide stripe along the end, with presumable a second stripe on the other end out of view. It resembles a Federal issue blanket and may be one, either captured and reused or carried by a Federal soldier at Antietam. We also cannot discount the possibility of items being moved by the photographer as “props” to make a more interesting image. It may also have been a British import, as some British blankets were noted as closely resembling Union blankets, or domestic manufacture, as Crenshaw Woolen Company produced grey army blankets. In the middle foreground is possibly a second blanket, although it is amidst other debris and is harder to analyze. It is light colored, probably white, and has at least two medium width dark colored stripes.8

With Lee’s Army returning from Maryland and with the winter of 1862-1863 looming, the War Department again issued an urgent appeal for civilian donations of blankets and warm clothing. The Crenshaw Woolen Company, having only recently signed its contract to produce woolen cloth for the Quartermaster Department, was paid in October 1862 to scour and clean donated blankets, drawers, quilts, shirts, comforts, socks, and bedding. Some of these items were captured Federal equipment being prepared for reissue, as the contract also included dying overcoats, coats, jackets, and pants.9

The domestic market for blankets had, by this time, been nearly exhausted. The increasing scarcity of blankets drove up their cost. Blankets that in 1861-1862 had cost $1.50, cost $7-8 by 1862-1863. Even damaged blankets were potentially valuable in a desperate market. Charleston auctioneer R. A. Pingle held an August 20, 1862, auction for two bales of damaged “English Gray Blankets.”10

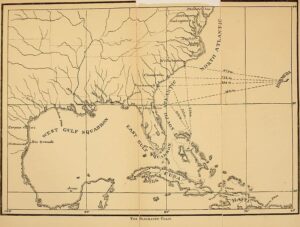

Importation promised a potential solution but faced extensive challenges. One of the two major eastern blockade running ports, Wilmington, closed in August due to an outbreak of yellow fever, forcing temporary reliance on the port of Charleston. Whether Charleston, Wilmington, or other ports, at least 105 attempts were made to run the blockade between September 1861 and December 1862, with 77 trips arriving successfully. These favorable numbers, however, conceal the highly risky nature of the business. Of the 36 ships that conducted these runs, 28 eventually ran out of luck and were captured or destroyed. With ship losses high and cargo space at a premium, the private companies on which the War Department relied prioritized their own, more profitable goods. The Confederate agent in Nassau, Heyliger, could only negotiate at best two-thirds of a ship’s cargo space and such a favorable percentage was usually only ever offered by John Fraser & Co. More goods were arriving from Europe than Heyliger could ship aboard blockade runners. A bottleneck developed, with only around half of the War Department supplies shipped from Europe to Nassau in 1862 actually reaching the Confederacy that year.11

On top of the challenge of finding cargo space, there was also the problem of paying for it, as well as for the supplies being purchased by Huse. Since the start of the conflict, the Confederate government had maintained a semi-official “King Cotton” embargo on the export of cotton. While the government’s preference for private industry to bring goods into the Confederacy may in hindsight seem inefficient, it was partially driven by necessity. Huse’s operation had been funded with an initial $5 million via Fraser, Trenholm & Co., but he and other Confederate agents in Europe were increasingly low on funds, particularly with so much being spent on the lofty freight fees charged by blockade runners. Having private enterprise import supplies and then buying the goods upon arrival, despite all its inefficiencies, allowed the War Department to pay with Confederate currency and bonds rather than via its limited holdings of foreign currency.12

Private firms, however, often failed to deliver. The Quartermaster Department had signed a massive contract in the summer of 1861 with “capitalists” to import 300,000 shoes and 100,000 blankets into the Confederacy. The promised goods, however, had not yet arrived a year later. Since signing the contract, prices had already increased by 100% and Myers was pessimistic the promised blankets would ever be delivered. As an alternative, Myers sought authorization to contract with companies to import critically needed quartermaster stores in exchange for cotton.13

In Fall 1862, Secretary Randolph formally requested President Davis overturn the cotton embargo and permit some government-sanctioned trading of cotton across enemy lines to obtain critical supplies from the North. “The alternative is thus presented of violating our established policy of withholding cotton from the enemy or of risking the starvation of our armies,” he wrote. Randolph recommended that the Commissary Department be permitted to sell cotton to buy bacon and salt and that the Quartermaster Department be similarly authorized to purchase blankets and shoes. Davis soundly rejected Randolph’s proposal and Randolph was soon forced to resign, replaced by James Seddon.14

Despite the repeated failure of firms to deliver on promises like those made for 100,000 blankets in the summer 1861, the War Department tried again to contract private enterprise to bring in critical supplies. In November 1862, commercial firm Vernon & Co. signed a series of massive contracts to provide British and European supplies for the Quartermaster Department, Ordnance Department, Medical Department, and Post Office. The firm was led by British national John M. Vernon, who had come to the South in 1849 and had been involved in manufacturing arms for the Confederacy in Wilmington. Delivery was to occur between February and April 1863 and invoices would be paid in cotton and tobacco.15

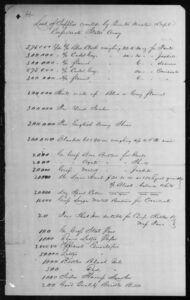

As part of this order, the Quartermaster Bureau ordered 200,000 blankets, measuring 92 inches long by 68 inches wide and weighing between 4 1/4 to 5 pounds, while the Medical Department requested 25,000 blankets and 6,750 coverlets. The contract also included 200,000 pairs of English Army shoes, 200,000 blue or gray flannel shirts, large amounts of cadet gray and blue wool cloth, flannel cloth, and 300,000 pairs of socks. Other contracts were for arms, ammunition, 12 large rifled cannons, rifles, gun barrels, pistols, and powder. While impressive sounding, there is no record of any portion of this contract ever being fulfilled. Vernon himself attempted to sail from Charleston in July 1863 aboard a steamer loaded with cotton, but the ship was destroyed trying to depart.16

Also in November 1862, two French brothers proposed a scheme to import 100,000 blankets, 100,000 pairs of shoes, 100,000 yards of flannel, and a million pounds of bacon or pork. The supplies, the brothers proposed, would be transported on French ships under the protection of the French consul through occupied New Orleans and up the Mississippi for delivery to the Confederacy at Port Hudson or Vicksburg. No further record of this effort could be located, and it is highly questionable that the Union navy would have permitted ships, even flying the French flag, to freely sail up the Mississippi. Like the Vernon & Co . contract, this proposal appears to have yielded no results.17

While other businessmen sought opportunity, John Fraser & Co. continued its steady and highly lucrative trade into the South. On November 12, 1862, Heylinger in Nassau informed the War Department that the Kate, owned by Fraser, was again loaded and ready to sail. “Her cargo consists chiefly of blankets, flannels, &c., and as these are so greatly needed at home, I have refrained from pressing any Government freight [from the Fraser-owned Melita].” The remainder of the Melita’s cargo was dispatched within the next month, with the final portions sailing via the Herald (also known as Antonica) and the Leopard. “Both the Antonica and Leopardcarry a large quantity of iron plates, a considerable shipment of woolens, all the blankets and shoes that could be got together, and a variety of other useful stuff on private account,” reported Heyliger. Within the next two months, Heyliger expected another ten ships to arrive in Nassau carrying “no less than 100,000 pairs of shoes and a vast quantity of blankets… irrespective of some private ventures which will increase the amount.”18

While Heylinger shuffled cargos in the Bahamas, on December 3, 1862, the Jusitia landed in Bermuda from England. John T. Bourne, a Bermuda merchant who served as a Confederate commercial agent in the islands, noted it was loaded with “blankets, boots & shoes, medicines, and what the South are actually in want of. I would run the cargo in as soon as possible.” The huge ship’s cargo, some 93,000 pounds worth of blankets, boots, shoes, and clothing belonging to John Fraser & Co., was packed in warehouses to await transshipment to smaller, faster blockade runners for the final sprint past Federal warships. Just days after the Jusitia arrived, Bourne dispatched “500 odd bales blankets, boots, and medicines…” from the Jusitia onboard the Confederate government-owned blockade runner Cornubia. The Cornubia delivered its cargo safely into Wilmington on December 17, the port having just reopened following the yellow fever quarantine. The vessel then made subsequent runs on January 30, 1863 with 157 bales mixed between shoes and blankets and on March 1 with 130 bales of shoes and blankets, likely the remainder of the Jusitia’s cargo.19

While private speculators continued to overpromise or overcharge, Huse continued his purchasing efforts in England. “In addition to ordnance stores,” wrote Gorgas in praise of Huse, “using a rare forecast, he has purchased and shipped large supplies of clothing, blankets, cloth, and shoes for the Quartermaster’s Department without special orders to do so.” Despite having had no authorization for the purchases, Huse reported by circa December 1862 having shipped £110,525 worth of quartermaster storers, including 62,025 blankets valued at £23,903.20

On January 3, 1863 Secretary of War Seddon reported to Davis: “For some of the leading articles required by the [Quartermaster’s Department] has necessarily been placed to a considerable extent on foreign supplies, since they are not adequately furnished within the Confederate States. This has specially been the case with woolens and leather, and under the losses and interruptions caused by the blockade there have been at times rather scant supplies of blankets, shoes, and some other articles of clothing.”21

Despite Huse’s best efforts, commercial schemes, and a fall 1862 surge in civilian donations, frequently inadequate supplies of blankets and shoes were increasingly on the minds of state authorities in late 1862 as cold weather threatened. The Governor of Alabama had written in August to the Secretary of War asking whether the Confederate government would be able to provide “blankets and clothing for our Army… which can be relied on to carry it through the coming fall and winter.” He was particularly concerned about blankets and other heavy woolen goods. “The little wool we have in the state is bearing an enormous price, and the conduction of the Mississippi presents serious obstacles in obtaining supplies from Texas.”22

Similarly concerned, Governor Zebulon Vance of North Carolina drew the attention of his General Assembly in November to “the great and almost insurmountable difficulties encountered by the quartermaster’s department providing clothing, shoes, and blankets.” “At the opening of the second winter of the war between the Confederate States and the United States of America,” declared Vance, “the State of North Carolina is under the necessity of applying in foreign markets for material with which to equip its citizens in the Army, especially for shoes and blankets.” Spurred by the urgent need, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia all explored different avenues to supply blankets for their sons fighting in Lee’s army and other Confederate forces.23

Let Every One Contribute Liberally – South Carolina

South Carolina soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia were “nearly naked, having lost or worn out the little clothing and blankets they had,” according to a fall 1862 report. “The fact being undeniable that our soldiers are without shoes, and in rags, and without blankets.” The state’s governor had, in 1861, purchased quantities of blankets, shoes, woolen cloth, and other essentials but these had been almost entirely exhausted by January 1862.24

One of these early import blankets may have been issued to South Carolina soldier Ebenezer Stenhouse. Born in Scotland, Stenhouse enlisted in April 1861 as a sergeant in the Second Palmetto Regiment. After being wounded in the breast at the First Battle of Manassas, Stenhouse was elected Third Lieutenant of his company in October. The following spring, however, he was absent sick with pneumonia and had been dropped from the roles by May 1862. His blanket, which is now in the collection of the South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, is made of blue-gray wool and has a twill weave like that seen on North Carolina blankets which will be discussed in the following section. Each end of the blanket has a wide dark blue stripe, again like the blankets imported by their sister state to the north.25

To meet the continued demand for blankets, South Carolina turned to a unique private, commercial, and public partnership. In October 1862, concerned citizens in Columbia founded the Central Association for the Relief of the Soldiers of South Carolina. The charity group immediately called for donations: “If necessary to the keeping up of our army in the field, and, therefore, to the success of our cause in establishing our independence, it would be a false pride, and a silly one, to object to sharing our blankets; and our wardrobe with our soldiers…. Let every one, then, come forward… and contribute liberally… in blankets or woolen carpets as a substitute for blankets. The quilted ‘comforts,’ so called, are not considered so useful to the solider as the blanket, which is easier dried after being wet. Let the ‘comforts,’ then, be retained for use at home, and our blankets be sent to our soldiers.”26

The group appears to have had immediate impact. The following month the state’s governor reported that “recently large supplies of clothing and blankets have been sent… to our soldiers in Virginia.” His call for appropriation of funds for additional supplies was met, in February 1863, with a bill authorizing $100,000 to be given to the Central Association for the Relief of the Soldiers of South Carolina “to be expended in purchasing, and forwarding to our soldiers, shoes, blankets; and clothing.”27

Simultaneously, the legislature authorized the incorporation of several companies which would play a critical role in supplying South Carolinian and other Confederate troops. The Importing and Exporting Company of South Carolina, the Atlantic Steam Packet Company of the Confederate States, and the Palmetto Exporting and Importing Company were all authorized to export produce from South Carolina and import from neutral ports “arms, munitions of war, and other commodities.” Formed to exploit the booming blockade running business, most of these companies included the ever-present John Fraser & Co. among their stockholders.28

These commercial firms formed a mutually supporting partnership with the state’s Quartermaster Department and the Central Association. In the winter of 1862-1863, the Central Association purchased a large lot of blankets at an advantageous price from the state Quartermaster to supply one of the South Carolina brigades in the Army of Northern Virginia. After this time, the state Quartermaster appears to have reduced its direct role in supplying blankets, as the department reported in October 1863 that it had only 294 blankets currently on hand and had issued only two in the previous ten months. The Central Association, conversely, had shipped some 2,401 packages worth some $185,373, primarily to the Army of Northern Virginia. As of November 1863, the Central Association had on hand $18,597 worth of “clothing, woolen, blankets, &c.… a part of which will be sent off next week.”29

As 1863 turned to 1864, South Carolina Governor Milledge Luke Bonham wrote to William C. Bee, president of the Importing and Exporting Company of South Carolina, requesting the firm import “blankets, shoes, clothing, arms, ammunition, machinery and the usual agricultural implements which we cannot manufacture.” Bee, whose firm operated blockade runners such as the Ella and Annie, the Eliza, and the Ella No. 2, was already heavily invested in this area. In December 1863 alone, his company sold 4,790 pairs of blankets to the Confederacy.30

The following year, the Central Association made large purchases from the South Carolina Importing and Exporting Company of clothing, shoes, coffee, and sugar at favorable rates, although it is unknown whether they also purchased blankets. The firm did, however, continue to import blankets, bringing in via Ella No. 2 in October 1864 120 bales of blankets measuring some 1,542 feet and 6 inches in length. Between November 1863 and November 1864, the Central Association distributed 1,425 blankets, 937 of those to the Army of Northern Virginia. They had, during this same period, procured some 1,447 blankets, including the purchase of 669 blankets, the manufacture of 666, and the donation of 87 blankets.31

A Most Complete Success – North Carolina

While South Carolina sought to supplement the blankets issued to its troops, North Carolina took on the entire burden of supplying her sons. Early in the conflict the state struck an agreement with the Confederate War Department that North Carolina would fully supply its own soldiers in exchange for limited intrusion by the Confederate Quartermaster Department in North Carolina’s domestic industry. In August 1861, the governor reported the initial success of this arrangement, stating that North Carolina had “been flattered with the compliment of sending the best equipped troops that have gone to Virginia, and we are taking every means of continuing these comforts. The subject of blankets and winter clothes for the troops has occupied our attention, and we are making efforts and appeals to accomplish this necessary object.”32

On September 20, 1861, however, the North Carolina legislature passed a law requiring the governor, acting through the state Quartermaster Department, to fully supply clothing to North Carolina troops in the field. Little preparations had been put in place for the long-term supply of the state’s soldiers, as the presumption was that Confederate authorities would assume that task after the state carried the burden of initial equipment. With it becoming increasingly apparent that the Confederate Quartermaster Department would be unable to adequately supply the armies, the North Carolina legislature passed this responsibility to the state quartermaster operation. The law also reorganized the Quartermaster Department, resulting in the appointment of Major John Devereux as Chief Quartermaster, a post he would hold until the end of the war.33

“Immediate steps were taken to comply with the law,” reported the state’s adjutant general, “and although there was no clothing on hand at its passage, before cold weather most of the troops were supplied with clothing and blankets, at least so far as to prevent any suffering.” As part of the reorganization, the North Carolina Quartermaster Department opened a clothing manufactory in Raleigh in September 1861. Initially under the command of Captain Isaac W. Garrett, it passed to Major Clement Dowd in 1863.34

Without the means to produce adequate woolen blankets, Garrett turned in this first winter of the war to an expedient substitute. He began purchasing all the woolen carpeting he could obtain, cutting it into quilt-sized pieces and lining them with coarse cloth. The Raleigh Clothing Manufactory produced 11,952 carpet blankets in its first year of operation, along with 2,801 wool blankets. Agents were dispatched to purchase available blankets across the state and as far away as New Orleans. Between Garrett’s operation, purchases, and donations of blankets and quilts, the North Carolina Quartermaster Department issued 28,185 blankets between September 1861 and 1862.35

Like the rest of the Confederacy, however, domestic sources were quickly exhausted. By fall 1862, the state adjutant general reported: “Some articles are very difficult to be obtained at any price, especially blankets and shoes. The former cannot be had, not is there any material out of which they can be made, as all the carpeting in the market was purchased last year. Arrangements have been made to supply cotton comforts in lieu of them; and although not so good as blankets for camp service, it is hoped they will answer at least to prevent suffering.”36

Early in the conflict, General James G. Martin, chief of all North Carolina war departments, had sought the governor’s approval to begin importation of foreign supplies, but as his term was concluding, the governor deferred the decision to incoming governor Zebulon Vance. Martin’s proposal for the state to begin exporting and selling cotton to fund importation of foreign material induced spirited debate over the legality of the state involving itself in a business venture and the potential loss of public funds. A judge warned Vance and Martin that their involvement in the scheme might be grounds for impeachment, but Vance decided to take the risk and gave Martin his approval.37

Martin dispatched John White as a special commissioner to Liverpool in late 1862. White spent the first few months of 1863 selling bonds backed by North Carolina cotton. Working with British firm Alexander Collie & Co., he purchased and had shipped to Bermuda 25,887 pairs of gray blankets, 26,092 pairs of army shoes, 37,092 pairs of woolen socks, 1,956 Angola wool shirts, 7,872 gray flannel shirts, 1,006 overcoats, 1,002 jackets, 1,010 pairs of pants, and large amounts of wool cloth and flannel. When he left England in early December 1863, an additional shipment of 10,000 pairs of gray blankets, 20,000 pairs of shoes, 1,920 flannel shirts, wool cloth, and cotton and wool cards was expected to ship by January 1864.38

In November 1863, Vance reported the fruits of White’s labors. “The enterprise of running the blockade and importing army supplies from abroad has proven a most complete success,” he informed the General Assembly. “Large quantities of clothing, leather and shoes, lubricating oils, factory findings, sheet-iron and tin, arms and ammunition, medicines, dye-stuffs, blankets, cotton bagging and rope, spirits, coffee, &c., have been safely brought in…” Over 2,000 bales of cotton had been exported to Liverpool. Vance predicted that the state had adequate quartermaster stores to cloth its soldiers through at least January 1865, but additional shipments of blankets and shoes would be required.39

Records of quartermaster issues to North Carolina troops during this period similarly show the impact of these imports. Between September 1862 and March 1864, the state Quartermaster Department transferred 33,164 blankets to Confederate authorities to be issued to soldiers from North Carolina. During the winter of 1862-1863, this number included 2,249 cotton comforts and 1,338 quilts, but after this period these expedients fall away in favor of imported woolen blankets. A typical receipt from the quartermaster depot in Raleigh documented the arrival of 3,402 heavy English blankets on October 31, 1863. Some 2,080 of these imported blankets were issued to the North Carolina soldiers in Cooke’s and Kirkland’s Brigades of the Army of Northern Virginia between October 1863 and March 1864.40

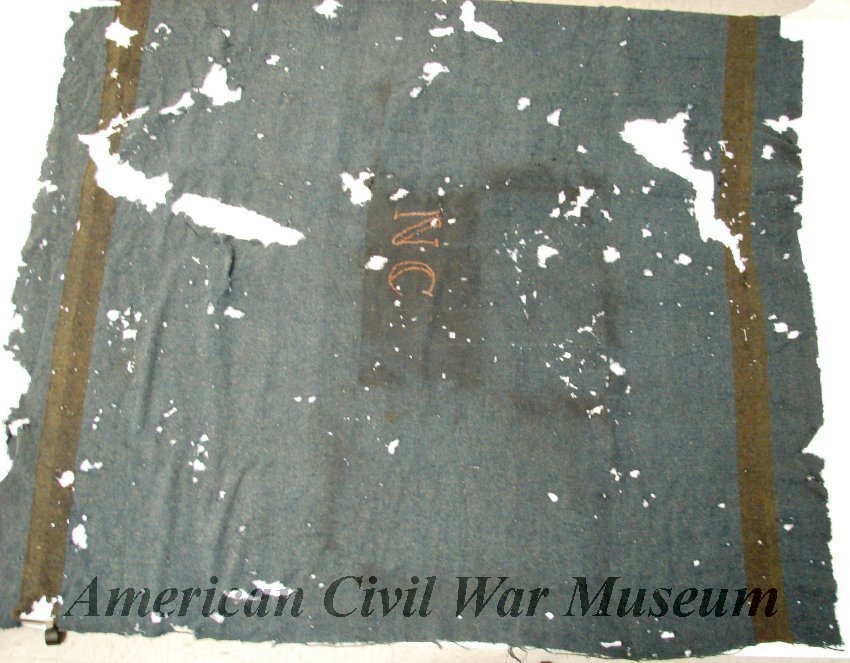

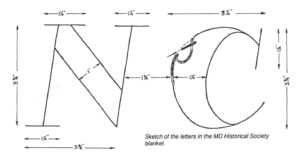

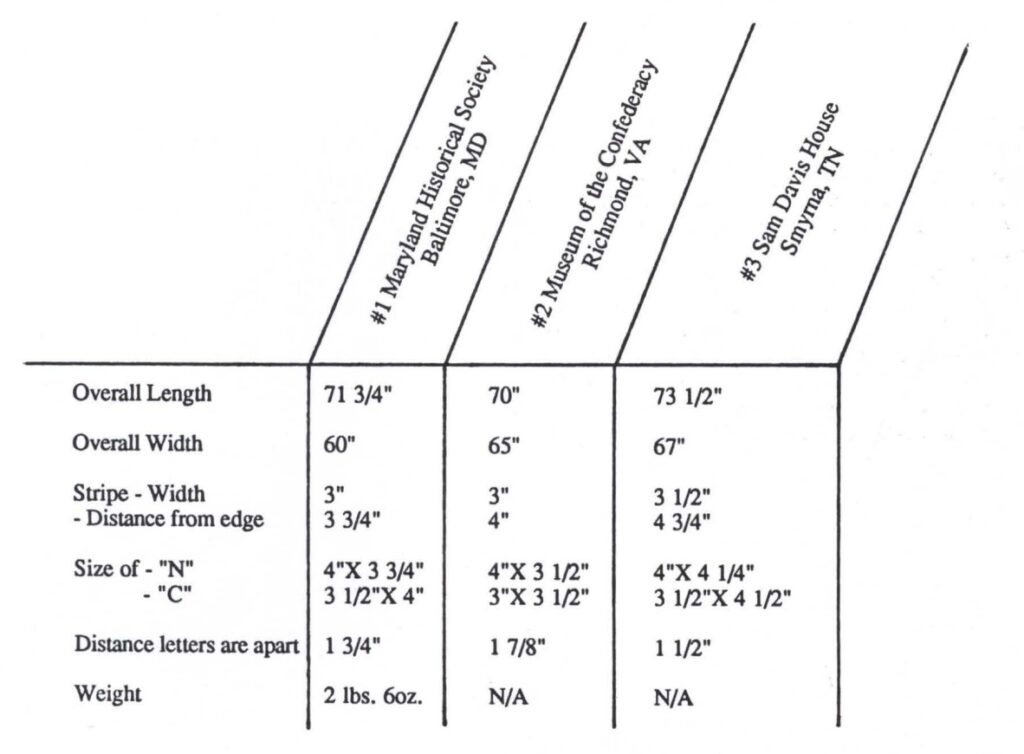

At least three of the blankets imported by North Carolina survive and closely resemble each other, suggesting they were made by the same unidentified British manufacturer. All three are woven on a power loom using cobalt blue yarn in a 2/2 twill weave. The blanket are lightly napped and have stripes on each end that were probably originally black. They are all marked with the letters ‘NC’ hand embroidered in the middle of the blanket using rose yarn that was probably originally a deeper red. Researchers David Burt and Craig Barry have speculated White requested his British suppliers mark these blankets as belonging to North Carolina to avoid confusion, the same way that North Carolina stamped imported arms ‘NC’ after several early arms shipments were taken by Confederate authorities upon arrival. Of note and as discussed above, the blanket carried by South Carolina soldier Ebenezer Stenhouse is relatively similar to the North Carolina blankets, omitting only the ‘NC’ and possibly suggesting the states used the same manufacturer.41

The first blanket is held by the American Civil War Museum and belonged to Captain John Stark Ravenscroft Miller of First North Carolina Infantry. Miller, who served as the regiment’s adjutant in the first year of the war, was promoted to command of Company H in October 1862. While no record survives of Miller being issued or purchasing the blanket, his company did receive 15 blankets in the final months of 1862 and at least two additional blankets in March 1863. Miller was killed in action at the Battle of Second Winchester on June 15, 1863, likely making his blanket one of the first purchased in England by White.42

Miller’s blanket is made of blue wool woven in a 2/2 twill pattern. Close examination of the material shows it contains shoddy, as various light-colored fibers can be seen amidst the blue. The blanket is 67 inches wide and 71 inches long, with a 3 inch wide stripe located approximately 4 ½ inches from each end. Although these stripes currently appear green-brown, historian Frederick Gaede believed these stripes were originally black and oxidized to its current color. The blanket is marked in its center with the letters ‘NC’ stitched in red yarn.43

The second blanket was donated to the Maryland Center for History and Culture. It was reportedly purchased in 1864 in Charlotte, North Carolina by a Lieutenant E.H. Browne of the Confederate Navy for $125. The museum describes the blanket as being cobalt blue with a woven twill and a medium brown stripe woven on opposite ends of the blankets. As with the Miller blanket, an ‘NC’ is embroidered in the center with red yarn. It measures 58 inches wide by 71 ¾ inches long. The Museum was unable to locate the blanket in 2011 for a Civil War sesquicentennial exhibit, although museum staff report it is almost certainly somewhere in the museum’s old textile storage area and will be rediscovered in the future.44

A third blanket is in the collection of the Sam Davis House in Smyna, Tennessee. It was reportedly bought at auction in Charleston by a Major J. Burrows Tree and was presented to the Sam Davis House by the Nashville chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. It being bought at auction upon arrival further supports the theory that the blankets were marked ‘NC’ in England prior to shipment, although it is unclear why the blanket was sold at auction rather than being delivered to North Carolina authorities. This blanket is the largest of the three, measuring 67 inches wide and 73 ½ inches long.45

The following analysis by Frederick Gaede details each of the three blankets:

In early 1864 Vance informed the Confederate War Department that North Carolina currently had at Bermuda or en route 8 or 10 ships bearing 40,000 blankets, 40,000 pairs of shoes, and large amounts of army cloth and leather. North Carolina had also purchased 112,000 pairs of cotton cards, dye, lubricating oil, and machinery to refit 26 cotton and woolen mills in the state. A September 30, 1864 statement of goods issued and sold by North Carolina from foreign importation included 31,000 blankets. At that time, the state Quartermaster still had 26,886 blankets on hand.46

Speaking after the war, Vance reported that the North Carolina state Quartermaster Department had distributed over 50,000 blankets during its operation. “Not only was the supply of shoes, blankets and clothing more than sufficient for the supply of the North Carolina troops,” he recounted, “but large quantities were turned over to the Confederate Government for the troops of other States.” When hostilities ceased, the state still had 96,000 uniforms on hand, along with “great stores of blankets, leather, etc.”47

Her Sons Shall Not Suffer – Georgia

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, Georgia’s governor Joseph Brown had taken efforts to stockpile military supplies. Before even leaving the Union, Georgia obtained from England 10,000 pairs of blankets, the same number of shoes, two small gunboats, and a supply of powder and shells. In March 1861, Brown wrote to the newly appointed Confederate Secretary of War asking whether Confederate authorities would supply volunteers with tents, accouterments, and knapsacks. “We have on hand, and on the way from New York,” he wrote, “quite a supply of blankets and some clothing for soldiers.”48

In April 1861, as tension around Fort Sumter grew, Confederate authorities requested Georgia provide powder and shells from its stockpile to bombard the fort. Brown readily agreed, but only on the condition that the Confederate government purchase his entire stockpile of blankets, shoes, and munitions. Despite efforts at negotiation, he proved unwilling to budge from this demand and the Confederate government ultimately paid for all the supplies in gold.49

Later that year, Brown dispatched Colonel Jean Alexander Francoise LeMat, inventor of the famous revolver, to Europe with orders to purchase 5,000 pairs of “French or English soldier’s pattern” blankets and promised to pay $4.50 per pair of blankets upon delivery. Georgia further sought to purchase 5,000 “pairs of sewed shoes, French or English soldier’s pattern, nailed soles and heels” and 2,000 British Enfield rifles. It is uncertain, however, whether LeMat’s efforts ultimately secured any blankets.50

Two years later, the state Quartermaster General reported on his work in response to legislative appropriation of funds to “procure and furnish clothing, shoes, caps or hats, and blankets for the soldiers from Georgia.” His March 1863 report detailed issues of supplies to units in the field and supplies remaining on hand but made no mention of blankets. That fall, Brown reported that the state quartermaster operation had nearly 40,000 suits of clothing on hand but “has been unable to get blankets and it has been very difficult to procure shoes.”51

To meet this unmet demand, the Georgia state Quartermaster pursued a dual course of domestic production and foreign importation. With no mills available to produce woolen cloth of sufficient weight and width for blankets, the state quartermaster began manufacturing in 1863 some 10,000 blankets out of jean and kersey cloth lined with cotton shirting. Brown also dispatched Colonel William Schley to England to purchase a 50 percent interest in a steamer on behalf of the State of Georgia. Anticipating shipments from abroad, in February 1864, the state commissioned George Harriss of the firm of Harriss & Howell to act as Georgia’s agent in Wilmington, authorizing him to receive, store, and forward arriving shipments of blankets, clothing, and other equipment.52

Schley, however, proved unable to purchase a steamer as originally planned. Brown turned, instead, to the Importing and Exporting Company of Georgia, signing a contract in March 1864 to charter their ships Little Ada, Florrie, Little Hattie, Lillian, and a fifth ship, the Emma Henry, currently under construction in Glasgow. Colonel C. A. L. Lamar was appointed agent of the State of Georgia to take charge of state efforts to export cotton and import war supplies. Schley shipped a consignment of 30,000 British military blankets to Nassau and Lamar loaded the Little Ada with 300 bales cotton in Charleston to pay for the shipment.53

The Little Ada, however, remained floating in port for nearly three months because it was unable to obtain clearance from the Confederate government. The Secretary of the Treasury disagreed with Brown over whether Georgia had to reserve half of each vessel’s cargo for use by the Confederate government and refused to authorize departure of the Little Ada. An indignant Brown, always strongly protective of Georgian states’ rights, blasted back, proclaiming that Georgia’s “sons are in the field. They need blankets, shoes, clothing and other necessaries. The Confederate Government is often unable to furnish these, and they suffer for them. The State… says her sons shall not suffer, and if the Confederate Government cannot supply these necessary articles, she will.” He demanded the Little Ada be allowed to depart to “pay for blankets to be imported for Georgia troops in service who have great need of them.”54

The Little Ada was finally cleared and sailed form the Santee River on June 10, 1864, bound for Nassau. The ill-fated ship’s career as a blockade runner, however, was short-lived, as she was captured the following month by the USS Gettysburg. The other ships chartered by Georgia, however, had better luck. In June the Lilian and the Florrie both arrived in Wilmington carrying 45 bales and 56 bales of blankets respectively. Another shipment of 12 bales of blankets arrived on the Little Hattie the following month. The shipments quickly reached the troops, as Georgian officer Edward Porter Alexander wrote from near Richmond that “… I laid under a pine, on a nice pair of new white blankets I had been allowed to buy out of an importation of the blockade by the state of Georgia for Georgia troops.”55

The Lilian returned to Bermuda in July, where it was loaded by Major Norman Walker, Confederate agent and Quartermaster at St. George’s with blankets, arms, ammunition, bacon, flour, etc. for shipment to Wilmington. Three days out, the Lillian was spotted by a Federal warship. During the chase, the Lillian lost a boiler, reducing the steamer’s top speed from its usual 12 knots down to 8 knots. The ship’s crew were uncertain their injured vessel could make the sprint past the Federal blockaders positioned near the Cape Fear River approaches to Wilmington. One of the crewmen, purser James Sprunt, described the steamer’s final approach to Wilmington in the early morning hours of July 30:

“At the first streak of dawn we were off Masonboro Sound, and soon after distinguished through the haze no fewer than eight blockaders apparently waiting to gobble us up. To our astonishment, however, they took no notice of our approach, as our ship was painted the exact color of the sand dunes along the beach, which we hugged as closely as we dared, and steered straight for the fleet, through which we passed without a gun being fired….”56

The Lillian successfully delivered its cargo to Wilmington, but the blockade runner’s luck had been exhausted. On its way out of Wilmington on August 24, the Lillian was captured by the USS Keystone Stateand USS Gettysburg.57

Despite the loss of the steamer, shipments of blankets and other supplies continued, with Schley arranging purchases in Europe and Colonel Lamar and Colonel A. Wilbur organizing imports and exports. In October 1864 the state Quartermaster reported that over the prior year he had issued 4,229 domestically-produced jean blankets and still had 4,895 on hand, plus three bales of imported British blankets in preparation for winter requisitions. The following month, Brown reported Georgia had exported some 1,614 bales of cotton valued at over $5 million. 30,000 army blankets were awaiting shipment in Nassau and Brown expected 5,000 full uniform suits, 18,000 yards of cloth, and 5,000 shoes to be delivered before December. Brown also appointed M. B. Peters to be Georgia’s agent in Charleston. Combined together, Georgia issued 7,504 blankets during 1864, increasingly drawn from abroad.58

Georgia’s efforts to import blankets and other supplies continued up to nearly the end of the war. In March 1865, Brown informed the General Assembly that, since November, six ships had been dispatched from Nassau with blankets and cotton cards. Two ships had been lost enroute, but the other four had arrived safely. With the loss of the last major Confederate ports at Wilmington and Charleston, Brown appointed a Mr. A. Alexander of Muscogee County as Georgia’s agent authorized to ship from Nassau to Georgia by way of the mouth of the Chattachoochee River, “all the cloth, ready-made clothing, shoes, blankets, buttons, thread, &c., which the State has stored at Nassau.” This scheme never produced results, and, after the end of the war, the state appointed Leopold Wantzfelder as its agent to sell off all “blankets, shoes, cloth, soldier’s clothing, buttons, trimmings, and all other property” in Nassau.59

Very Little in Excess of Immediate Demands – Virginia

Virginia, meanwhile, appears to have considered taking steps to augment Confederate issues of blankets to their troops, but ultimately took limited action. The state Quartermaster focused exclusively on outfitting Virginia State Line forces that remained under state control and responsibility. By December 1862, the state Quartermaster had purchased 5,725 blankets, the second largest expense for the department after uniform cloth. During the year, some 3,637 blankets had been issued to the State Line via the Quartermaster in Wytheville.60

The Quartermaster reported: “No such statement accordingly accompanies this report, but I may safely say that the materials on hand, and the articles of shoes, socks, blankets, &.c., reported as purchased in the south, are very little, if any, in excess of the immediate demands of the troops….” The commander of the State Forces, Major General John B. Floyd, strongly disputed claims that his troops were adequately supplied. In November 1862 he wrote that the State Line was “without shoes, blankets, pantaloons, coats, shirts, socks, and almost every other article necessary to live in camp… There are hundreds of men here without shoes and without coats and blankets.”61

Dismayed by these reports, the state Quartermaster personally visited Wytheville. “The result of my investigations,” he wrote Floyd, “are that the inefficiency in the departments alluded to is seen after leaving Wytheville. It is notorious, that whilst your command has been suffering for clothing, blankets, shoes, &c, more than sixty wagon loads of such supplies were at Greever’s — at which point also an abundance of transportation was found lying idle, for want of proper control and direction.”62

Floyd, however, remained unsatisfied. “A large number of the men are without shoes and blankets, clothes, tents and cooking utensils,” he complained in January 1863, “and among three regiments there are only five axes, and not spades and picks enough to bury the dead.” The quartermaster, however, had little left to provide. An additional 124 blankets were sent to Floyd in January and early February, leaving the state quartermaster with only 60 blankets still on hand.63

The state’s efforts, however, to keep Floyd’s troops supplied did little to benefit the thousands of Virginians serving in the provisional Confederate army. Hearing continued complaints, the Virginia House of Delegates charged its Committee on Military Affairs to research a bill “authorizing the governor to import a supply of shoes and blankets for the use and benefit of the Virginia troops in the confederate army.” After the committee reported such an effort would be impracticable, they were next charged in December 1863 with researching a possible bill to authorize the purchase of surplus blankets in the state and, if purchase provided ineffective, to impress the required blankets. Again, the committee failed to advance a bill.64

Trying again the following month, the Committee was directed in January 1864 to simply confer with Confederate authorities to determine whether the Confederate Quartermaster Department would be capable of supplying Virginia soldiers with adequate blankets, shoes, and clothing. This effort finally produced a draft bill and in March 1864 the House of Delegates passed a bill “to provide for the purchase of shoes, blankets, and other articles of clothing for the troops of this state in the service of the state or of the Confederate States.” All these legislative efforts, however, do not appear to have produced results and Virginia never entered into the types of state-directed importation or private-public partnerships seen in North Carolina, South Carolina, or Georgia.65

The Most Destructive and Disastrous Conflagration

As state-run quartermaster operations remained in their early stages and the Confederate Quartermaster Department struggled to pay for and ship supplies, the winter of 1862 was particularly harsh for men of the Army of Northern Virginia. On November 1, the Richmond Whig printed a letter written by an anonymous private in Lee’s army. “Huddled around a scanty fire,” he wrote in description of the Army of Northern Virginia, “with no tent to shelter them from the inclemency of the season, with no clothing to protect them from the piercing cold, with no blankets to wrap them in the few hours [of] sleep, and no shoes to cover their feet on the rugged marches.”66

Later that month, a Charleston reverend just returned from visiting the army reported “There is great want of everything, and especially of shoes and blankets. Send on immediately.” Soldiers reportedly marched through snow barefoot and lacked adequate clothing. One brigade commander laid the blame squarely at Myers’ feet, claiming multiple requisitions for shoes had been rejected and Myers had callously remarked “let them suffer.” The scandal grew the following month when, the Richmond Enquirer claimed a sentinel had frozen to death while on duty at Camp Lee for want of proper clothing. A minister from Richmond visiting that day to distribute religious material, upon learning of the man’s death “very promptly bundled up his tracts and came to town to take up a collection for the purchase of blankets.” The city’s Young Men’s Christian Association collected donations of over 6,000 pairs of shoes and 7,000 blankets from Richmond citizens for distribution to needly soldiers.67

Myers tried to defend himself from the criticism, reporting that “many [blankets] were issued but the soldiers discarded their government issued blankets during the summer, many by the sides of the road after a day’s weary march.” The Richmond Clothing Bureau had, over the past year, issued 153,347 blankets and 320,000 pairs of shoes to Lee’s soldiers.68

While the men of the Army of Northern Virginia shivered and the Richmond papers sought to assign blame, Ferguson had finally arrived in England in late December 1862. He initially set up operation in Liverpool, before later moving to Manchester. His initial attempts to gain control of overseas purchasing for the Quartermaster Department, however, were challenged by Huse. Despite having only been charged with purchasing for his own Ordnance Department, Huse had taken for himself the role of de facto Quartermaster agent as well. He refused to cease purchasing quartermaster stores. “Huse has caused me more annoyance than all the others combined on this side,” complained Ferguson, “and has defeated my plans in a great measure for keeping up the supplies of our department.”69

Even more concerning, Ferguson had significant concerns regarding Huse’s near-exclusive supplier, S. Isaac Campbell & Co. Based on his knowledge of the textile industry, Ferguson judged the prices charged by S. Isaac Campbell & Co. were exorbitant and, upon examination of some of the fabric purchased by Huse, determined it was worth only roughly half the price Huse had paid. Perhaps most alarming, Huse admitted having personally accepted a commission from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. Investigation of Ferguson’s suspicions ultimately confirmed S. Isaac Campbell & Co. had been overcharging Huse by as much as 20% over the agreed upon commission. War Department financial agent Colin McRae, after completing the audit, reported “they have in many instances made charges that can be characterized by no other term that that of fraudulent.”70

Instead of relying on questionable middlemen like S. Isaac Campbell & Co., Ferguson began signing major contracts directly with British blanket mills and other suppliers. “My knowledge of the market will enable me in most instances to do without brokers, commission agents, and all classes of middle-men,” he would later write to his superiors in Richmond. “All that I want is explicit orders from you as to what is most needed and the money to buy them, and you may rest assured that the supplies will be sent forward with dispatch.”71

Soon after Ferguson’s arrival, the British steamer Peterhoff departed London on January 9, 1863. American diplomats in London suspected the newly constructed ship would make for Charleston. Instead, the vessel sailed for Texas. Although this Trans-Mississippi destination takes the vessel outside the scope of this study, its cargo is noteworthy due to the amount of detail available via legal disputes following its capture by the USS Vanderbilt on February 25, 1863. The cargo contained 192 bales of gray blankets “adapted to the use of an army, and are believed to be such as are used in the United States army.” These blankets were elsewhere described as “government regulation gray blankets.” These blankets were shipped by Grant, Brodie & Co., a commission merchant house in London operated by John Mactaggart Grant and Walter Brodie.72

The first major shipment of goods purchased by Ferguson were loaded aboard the Fraser, Trenholm & Co. ship Minna, which left Liverpool on February 9 bound for Nassau carrying more than 4,000 blankets, 15,00 pairs of blucher shoes, gray and sky blue uniform cloth, flannel, 10,000 brass buttons, 7,542 pairs of socks, and other supplies. “Valuable cargo,” summed up the local American Consul. The goods, however, were intercepted when the USS Victoria captured the Minna enroute to Wilmington.73

Undeterred by the loss of his first major shipment, Ferguson continued operations in England and other parties continued to ship goods. As of early May 1863, another Fraser, Trenholm & Co. vessel, the Beauregard, was believed to be enroute to Charleston with blankets, a battery of six guns, Enfield rifles, 500 bags of saltpeter, and other munitions.74

The Confederate Quartermaster Department suffered a significant setback to their domestic endeavors a few months into 1863. The Crenshaw Woolen Mill, so critical to the Confederacy’s war effort, was kept running around the clock by around 140 workmen and women producing woolen cloth. At around 2 o’clock in the morning of May 15, friction from components in the picking room started a fire, which quickly spread due to the highly combustible nature of the wool in the room. Efforts made to douse the flames were futile, as the hose proved too short to throw water on the now roaring blaze. “The city and country around were lightened to the brightness of mid-day,” described the Richmond Whig, “and the fresh breeze blowing at the time sent volumes of sparks far away through the night, presenting a spectacle of sublime grandeur which is seldom witnessed.”75

The blaze rapidly consumed the entire building, leaving only the charred brick walls and destroying over 30,000 pounds of wool, some 5,000 yards of fabric, and, most critically, all the factory’s machinery. The Richmond Daily Dispatch called it “one of the most destructive and disastrous conflagrations which the city has ever been called upon to suffer.”76

“This mill was the most extensive and valuable of its character in the Confederacy,” continued the Dispatch, “and its loss will be seriously felt.” At the time of its destruction, Crenshaw was making approximately 2,000 yards of double width woolen fabric weekly and, in a year, produced enough cloth to clothe 40-50,000 men. While the firm had never produced blankets directly for the Quartermaster Department, this extremely valuable domestic resource was now gone. The Department would now look exclusively overseas for blankets.77

From Crisis to Promise – Summer 1863

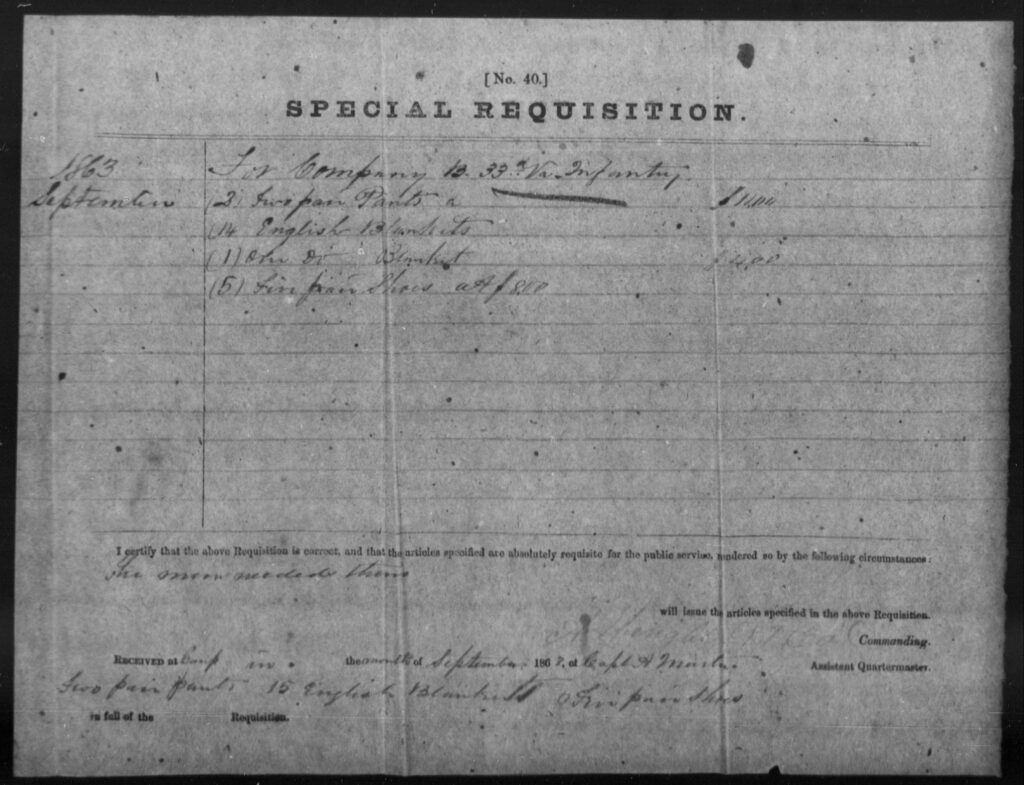

Even worst, by the summer of 1863 the Quartermaster Department was in financial crisis. The Treasury Department began routinely refusing to provide funds because War Department expenses far exceeded authorized levels. Soldiers had not been paid in six months and the department was running up significant debt with southern textile mills. Ferguson was spending heavily in preparation for the coming winter season, but available funds in Europe were rapidly drying up. The Secretary of War had instructed that other departments have priority when allocating the proceeds from European loans. Confederate military setbacks at Gettysburg and Vicksburg severely damaged Southern credit in Europe and some contractors began to refuse to extend Ferguson lines of credit.78

Intimately tied to the Department’s financial difficulties were continued shipping challenges. Davis had finally ended the de facto cotton embargo and authorized the War Department to begin exporting cotton to fund European purchasing. The challenge then became how to convert cotton into currency and hence into blankets and other needed supplies. Initially the government relied on private shipping to bring its cotton to market, but most firms prioritized lucrative commercial goods over government cotton and goods. The inefficient system of relying on private companies to bring in needed goods and take out government cotton as payment did not produce the volume of imports required. The Confederate government had, by 1863, directly purchased or obtained controlling interest in several steamers, but these vessels primarily supported the Ordnance Department and the Medical Department. Ferguson’s purchases for the Quartermaster Department had to be brought to the Confederacy via extremely costly shipping contracts with firms like Fraser, Trenholm & Co., forcing the War Department to pay exorbitated shipping fees and further exacerbating the financial crisis.79

Despite Davis’s reluctance to regulate private enterprise, it was finally apparent that dramatic action was necessary. In August 1863, Seddon ordered government agents to begin impressing half of the cargo space on all incoming and outgoing vessels to carry government cargo in and government cotton out. Anyone refusing would have their ship seized and impressed fully into government service. A February 1864 law formalized Davis’s power to regulate overseas shipping and formalized this requirement to reserve half of incoming and outgoing cargos for the government. These regulations were the cause of the dispute between Georgia and the Confederate government over the Little Ada previously discussed.80

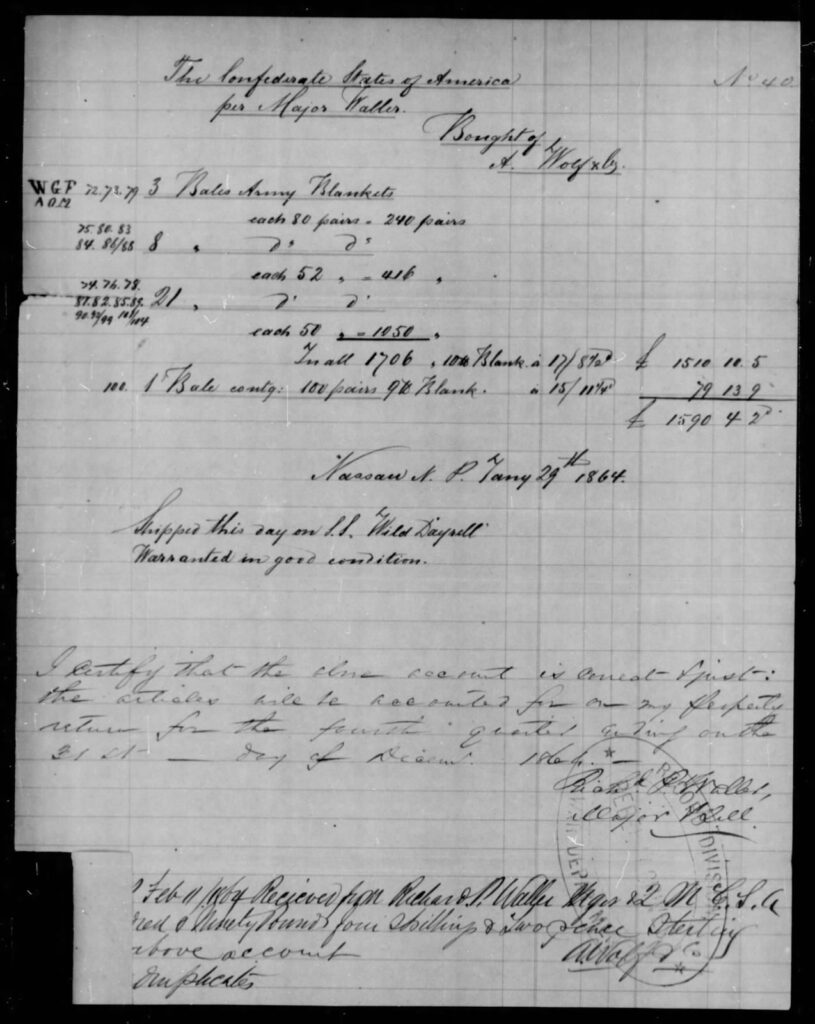

As might be expected, these regulations were extremely unpopular with ship owners. To provide a potential alternative, in Fall 1863 the War Department signed contracts with several shipping companies, including Power, Lowe & Co. and Davis & Fitzhugh, to run government cargo in and out of Southern ports. These contracts exempted the firms from impressment and sold them cotton at a lower price in exchange for an agreement to build or purchase new steamers and bring in entire cargos for the government. While the government got less for its cotton, these contracts increased the flow of quartermaster supplies into the Confederacy without the need for coercion through impressment. Power, Lowe & Co. were the agents and past owners of North Carolina’s dedicated blockade runner, the Advance. After the firm successfully brough in a shipment of shoes in early January 1864, a quartermaster in Wilmington proposed directly contracting with the firm to provide shoes and blankets for a 20% commission, although it is unclear whether anything came of this proposal.81

In addition to the impressment regulations and shipping contracts, the Quartermaster Department also sought to emulate the Ordnance Department and obtain its own dedicated vessels. In 1863 Seddon signed a contract with James and William Crenshaw, whose brother Lewis Crenshaw had been president of the Crenshaw Woolen Company, to purchase a line of 12 steamers that would prioritize importation on behalf of the Quartermaster and Subsistence Departments. The Crenshaws, in turn, entered into a partnership with British firm Alexander Collie & Co., already a prominent player in Confederate trade with twenty ships engaged in blockade running. North Carolina had also primarily worked through Alexander Collie & Co. to purchase and ship blankets and other supplies for state use. The three parties ultimately agreed the Confederate government would pay for three-fourths of the ships, with Crenshaw-Collie paying for the remaining fourth. Half of the ships’ cargo space would be dedicated to the War Department, the Navy Department would have a quarter, and Crenshaw-Collie would have the remaining quarter to import tax-free whatever goods they wished.82

While promising a steady supply of cargo space for the Quartermaster Bureau, the introduction of William Crenshaw as an additional player in Liverpool further muddled Confederate purchasing operations. William Crenshaw began making purchases via Collie’s firm, invoking the anger of Huse. Crenshaw tried to insist Huse’s purchases be shipped via the Crenshaw-Collie Line, while Huse tried to demand Crenshaw-Collie purchase supplies via Huse’s favored British firm, S. Isaac Campbell & Co. Meanwhile, while 12 steamers were eventually planned, only three were available by late summer 1863, with three more projected by the end of the year. The first of these ships, Venus, arrived in Wilmington on June 18, 1863 with 25 bales of 60 inch by 80 inch blue-grey blankets in her hold.83

Confusion occurred at home as well as abroad, with agents for different parts of the War Department sometimes competing to purchase newly imported supplies. The Chief Quartermaster for Joseph Johnston’s forces in Mississippi dispatched his own purchasing agent to Charleston in an attempt to directly obtain supplies. In July 1863, the agent purchased 20,000 imported blankets at auction. Myers was infuriated by this breach of protocol and seized the blankets before they could be shipped west.84

With multiple promising shipping developments underway, Myers dispatched Major Richard P. Waller to Nassau to better organize the blockade runners operating out of the Islands and eliminate the bottleneck that had plagued the Quartermaster Bureau since the previous year. Waller’s orders also authorized him to “purchase all shoes and blankets, either at Nassau or Bermuda, that you may consider suitable for the Army, at any price you may think best for the interests of the Confederacy.” This would be among Myers’s last contributions to the Confederate supply effort, as he was replaced on August 7 with Brigadier General Alexander Lawton.85

We are Now Destitute of a Supply of Blankets – Lawton Takes Control

Myers’s tenure as Quartermaster General had been plagued by his bureaucratic, inflexible nature. Lawton, however, was a former division commander in the Army of Northern Virginia and knew firsthand the suffering of ill-supplied troops. He also brought intellect and business savvy from his pre-war legal career. Lawton moved quickly to enact sweeping change in his department, seeking to emulate the example of self-sufficiency offered by the Ordnance Department. Despite all the challenges inherited by Lawton, initial prospects appeared promising. Ferguson had purchased large amounts of material in England, Waller was enroute to Nassau where the Quartermaster Department had an extensive stockpile of stores, the first few ships of the Crenshaw-Collie Line were in operation, and the government’s new impressment regulation promised increased availability of cargo space.86

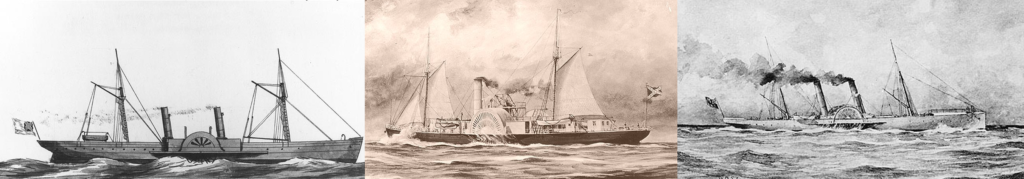

Waller had meanwhile arrived in Nassau on August 10, 1863 and set to work. Within three days, he had consolidated all the quartermaster supplies previously stockpiled by Heyliger and loaded them on a Crenshaw-Collie Line ship, the Hebe, for shipment to Wilmington. Waller supplemented the Hebe’s cargo with 21 bales of blankets he purchased locally in Nassau. This initial shipment, however, would serve as a harbinger of a challenging several months for Lawton and the Quartermaster Department. While trying to enter New Inlet near Wilmington on August 18, the Hebe was spotted by the blockader USS Shokokon, chased aground, and destroyed. Five days later, the USS Minnesota landed two boats to drive off the Confederates salvaging the wreck. “There was a quantity of rubbish on the beach,” wrote the Federal officer, “also some three or four bales containing cloth and blankets, and about three bales of the same which had been broken open and scattered on the beach prior to our landing, all of which had been damaged by fire, water, and dirt.”87

Thankfully, however, the Eugenie, a steamer owned directly by the Confederate government, had arrived safely in Wilmington on August 17 with a cargo that included 68 bales of blankets. The same vessel had previously delivered 100 bales of blankets to the Wilmington docks back in June, the only major shipments of blankets documented since March other than the June inaugural trip of the Venus. Some of the Eugenie’s cargo likely made it to the Army of Northern Virginia by September, as the Assistant Quartermaster for the Thirty-Third Virginia Infantry documented receiving and issuing at least 90 “English blankets” to his unit that month. Unfortunately, Eugenie was severely damaged while running into Wilmington in early September and would never return to active blockade running duty.88

Despite the deliveries from the Eugenie, the destruction of the Hebe came just as Lawton was facing mounting reminders that the impending winter would bring a surge in demand for blankets. A concerned Virginia politician wrote in September 1863 to Jefferson Davis stating: “You will feel surprised when I inform you that we are now destitute of a supply of blankets and overcoats for our troops this winter, and that there are no factories in the South engaged in the manufacture of blankets. We are dependent almost entirely on purchases in England, and so much risk is there attending this trade, that it amounts almost to a prohibition.” The same politician also contacted Lawton to express his concerns. Lawton, all too familiar with the challenges faced by his department after a month on the job, responded “there are several articles essential to the comfort and efficiency of our armies, that it will be impossible to provide this winter without relief from abroad. Blankets, for instance, are very scarce, and the facilities for procuring the same in the home market very limited.”89

Waller wrote to Lawton on September 10 and September 18 offering a potential additional source of blankets. If he could be forwarded funds, Waller wrote, he could obtain on reasonable terms 25-30,000 blankets, 20-25,000 pairs of shoes, large amounts of flannels and grey cloth, and other stores. Lawton, responded on September 28, stated that he would normally prefer to not purchase in Nassau, as the prices were higher than those available in Europe. However, he wrote, “In view of the approaching cold weather, the great scarcity of stores here, and the unfortunate loss of the steamer Hebe, I am constrained to resort for the present to the nearest point of supply to save time.” Lawton authorized Waller to make what purchase he could, giving “preference to such supplies as are most needed — blankets, shoes, and heavy material for overcoats.”90

In accordance with Lawton’s orders over the coming months, Waller would go on to purchase 2,300 army blankets in November 1863 from the local Nassau firm A. Wolf & Co., immediately dispatching the blankets via the Banshee. In January 1864, A. Wolf & Co. sold Waller 3,408 blankets sent via the Wild Dayrell, 1,460 blankets sent via the Mary Anne, 3,612 sent via an additional run by the Wild Dayrell, 1,624 sent via the Syren, and 2,036 blankets shipped aboard the Presto. Also in January 1864 Waller bought 898 “Army Blankets” from Jervey & Mueller, the Nassau-based arm of William Bee’s Importing and Exporting Company of South Carolina.91

So Much Needed for a Winter’s Supply – Fall 1863

Robert E. Lee wrote to Lawton in early October desperately requesting blankets and shoes for his men. Lawton responded: “Blankets are extremely scarce. About 4,000 have been issued to your troops within the past month…” These 4,000 blankets were likely those brought in by the Eugenie and included those issued to the Thirty-Third Virginia in September. Lawton continued, stating “the depot here (Richmond) [has] only 1,500, which with 12,000 at Atlanta, for [which] the commands in that section of the country are clamorous, constitute the entire supply; and unfortunately our domestic resources in this particular are very limited.” Lawton noted that a shipment of 10,500 shoes and 6,500 blankets had just arrived in Wilmington and declared “In view of the exhausted condition of our resources here, I am using every effort to draw a winter’s supply from abroad…”92

The recently arrived blankets referenced by Lawton were 43 bales of blankets brought into Wilmington by the Dee, another of the Crenshaw-Collie Line. Lawton was indeed making every effort to import more blankets. The same day he wrote to Lee, Lawton directed Ferguson to “expend in blankets, shoes, and material for overcoats, as heretofore instructed, these being the articles most needed… There is not a day to be lost in forwarding these supplies… winter is almost upon us and we have barely time, with the utmost dispatch, to procure from abroad some of these essential articles of supply which cold weather will render a necessity and which the exhausted condition of home resources forbids that we should expect to procure here… The early receipt of these supplies is rendered the more necessary by the fact that our depots are bare, and that a valuable cargo of blankets, shoes, and woolens forwarded by Major Waller from Nassau in the Hebe proved a total loss with that steamer.”93

Lawton penned similar letters the following day to Confederate Treasury agent Colin McRae in Paris and Major Walker in Bermuda, reporting that “the depots are quite bare” and domestic resources “nearly exhausted.” He pleaded with McRae for additional funds and asked if Walker could purchase supplies locally in Bermuda, noting that Waller had arranged for around 20,000 blankets, a similar number of shoes, and a large quantity of woolen cloth in Nassau. Meanwhile, Ferguson in England was authorized to purchase 300,000 blankets, although any purchases he made would not arrive on Confederate shores for months.94

Lawton’s losses, however, were only just beginning. Waller had loaded the remainder of the Nassau stockpile on a second Crenshaw-Collie Line steamer, Venus. Laden with quartermaster stores, Venus was spotted by the USS Nansemond near New Inlet just outside of Wilmington. Nansemond gave chase and forced Venus to become beached ashore, where it and its cargo were destroyed.95

Still reeling from the loss of the Hebe, Lawton now struggled to recover from this second blow. “I alluded to the fact that the loss of one of the Collie steamers, the Hebe, freighted with shoes and blankets, the articles most needed, had embarrassed me very much,” Lawton wrote to Ferguson on October 21. “I have now to add that that embarrassment has been greatly increased by the unfortunate loss of another vessel of the same line, the Venus, loaded, I fear, wholly on account of this department, and with supplies of a like character.”96

Two days later, Lawton informed Heylinger: “The loss of two steamers of the Collie Line [Hebe and Venus], on which we have been almost entirely dependent, has so straitened the resources of this department that the Secretary of War has consented that for the present any facilities at the command of the Government may be devoted to the special purpose of forwarding quartermaster’s stores, particularly such articles as blankets, shoes, and material for overcoats, so much needed for a winter’s supply.” Lawton similarly communicated these orders to Ferguson, Waller, and Walker, pressing them to do all in their power to provide blankets, shoes, and heavy cloth to make overcoats. Seddon, however, provided his own conflicting instructions to the agents to prioritize commissary stores, nitre, and lead.97

The loss of Venus and Hebe had also strained the relationship between Alexander Collie and his American partners. Collie wrote soon after “I regret very much to say that I fear the Crenshaw contract will not work out…. Owing entirely to a nasty jealous spirit which is not credible to those who indulge in it.” The Crenshaw brothers evidently claimed Collie’s personnel in Wilmington and Bermuda were harming the operations of the line. Collie, in turn, claimed the Crenshaws’ management of the joint vessels had been “far from good” and he did “not hesitate to affirm that the Venus was been lost solely through this.” Rather than the 12 ships originally planned, Collie announced his refusal to build any additional ships. The Crenshaw-Collie line would be limited to the surviving ship, Dee, and two more scheduled to enter operation before the end of the year, Ceres and Vesta.98

Despite Collie’s attempt to blame the Crenshaw brothers for the loss of the steamers, the setback had more to do with the movements of the Federal Navy. In July 1863, Union forces had invested Charleston and, following the early September capture of Fort Wagner, Charleston was effectively closed as a port. The Federal Navy shifted ships north from Charleston to augment the squadron at Wilmington, increasing the difficulty blockade runners faced reaching the Cape Fear River. Since the beginning of 1863, the half dozen ships efficiently operated by the Ordnance Department had made 22 round trips without a single loss. Now, they too began losing vessels. Soon after midnight on November 7, the USS James Adger and the USSNiphon captured the Ordnance Department’s Cornubia along with her crew and all her cargo. The following morning, James Adger chased down and seized the Robert E. Lee, another Ordnance Department steamer. On board, the vessel carried 214 large cases and bales of shoes and blankets (some bales weighing as much as two tons), 150 of cases Austrian Lorenz rifles, 250 bags of saltpeter, 61 barrels of salt provisions, and 30 pigs of lead. On the morning of November 10, USS Howquah captured the Confederate government-ownedElla after firing a glancing shot off her engine.99

Private companies lost ships at an alarming rate in November and December as well. The Importing and Exporting Company of South Carolina lost the Ella and Annie to a Federal boarding party, the Anglo-Confederate Trading Company’s Banshee was captured, and the Chicora Importing and Exporting Company’s General Beauregard and Antonica were both driven ashore and destroyed.100

Has Left Us in a Sad Condition – Winter 1863-1864

Not all was bleak, as some ships did still get through, allowing Lawton and his quartermasters to begin fulfilling some requisitions. Alexander Collie’s Hansa delivered 24 bales of French blankets on October 14 and another 30 bales on November 21. The government-owned Phantom brought in 35 bales of blankets on October 23 and the Crenshaw-Collie Line vessel Dee ran in an unknown number of blankets on November 6. North Carolina’s Advance landed 125 bales of blankets on November 10 and Fraser, Trenholm & Co. imported 30 bales of blankets on the Bendigo. Surviving records for the last shipment brought in by the General Beauregard before its December destruction detail the blankets being imported:

- 3 bales grey blankets 68”x85” (143 pairs)

- 4 bales blue-grey blankets 56”x80” (200 pairs)

- 4 bales blue-grey blankets 56”x85” (200 pairs)

- 4 bales blue-grey blankets (200 pairs)

- 4 bales brown-grey blankets 58”x82” (200 pairs)101

Even more details on this shipment are available from a shipping book in the National Archives recording movement of these blankets by rail from Wilmington to Richmond on November 26. The total number of blankets is higher than the records found elsewhere, possibly reflecting the incomplete nature of surviving documentation or mixture of cargos from multiple vessels. The Mackinaw blankets listed refer to an inexpensive, dense blanket popular along the northern American frontier due to its natural water repellent and extra warmth. Although woven with a twill pattern, after being woven the blanket was heavily fulled or felted, resulting in nap on both sides that concealed the weave and made the blanket warmer without additional cost.102

| Number of Bales | Number of Pairs | Color/Material | Dimensions | Weight |

| 3 | 143 | Gray | 68” x 85” | Not Noted |

| 4 | 200 | Blue Gray | 56” x 80” | Not Noted |

| 4 | 200 | Blue Gray | 56” x 85” | Not Noted |

| 4 | 200 | Blue Gray | 58” x 82” | Not Noted |

| 4 | 200 | Brown Gray | 58” x 82” | Not Noted |

| 2 | 200 | Gray Mackinaw | 56” x 82” | Not Noted |

| 2 | 300 | Single Gray | 56” x 84” | 6 lbs |

| 2 | 200 | Brown Gray | 56” x 78” | 5 lbs |

| 1 | 100 | White Mackinaw | 60” x 80” | 5 lbs |

| 1 | 100 | White Mackinaw | 56” x 84” | 7 |

| 1 | 100 | White Mixed Mackinaw | 56” x 78” | 8 |

| 1 | 100 | White Mixed Mackinaw | 56” x 78” | 5.5 lbs |

| 1 | 99 | White Mixed Mackinaw | 56” x 78” | 5.5 lbs |

| 1 | 99 | White Mixed Mackinaw | 60” x 80” | 6.5 lbs |

| 2 | 200 | Blue Gray Mackinaw | 56” x 78” | 6 lbs |

| 2 | 200 | Blue Gray | 56” x 78” | 6 lbs |

The Crenshaw-Collie Line, however, continued to have particularly poor luck. On her first attempt to run the blockade, the Ceres ran aground on the shoals outside Wilmington on December 6. Responding Federal ships found the stranded ship abandoned and her cargo ablaze. The ship had carried one of Ferguson’s largest cargos, with 26,000 blankets, 16,000 pairs of shoes, and 15,000 yards of heavy woolens abroad. The Vesta, also on her maiden voyage, also ran ashore and was destroyed on January 11, 1864. By early 1864, only the Dee remained of the Crenshaw-Collie Line, all the Ordnance Department’s ships were gone, and many privately owned vessels had been lost.103

The losses, particularly of the Crenshaw-Collie ships, continued to challenge Lawton’s ability to meet demand. Lee repeatedly raised concerns about the availability of blankets for his command, writing to Seddon in late October, “I hope you will endeavor to provide the army with shoes, clothing, and blankets, for the season is approaching when the want of these articles will entail great suffering and sickness on the troops, and incapacitate them for military movements.” In mid-December, Longstreet’s Corps in eastern Tennessee submitted a requisition for 10,000 blankets. Lawton was only able to send 3,600. Explaining why he was unable to fulfill the requisition in full, Lawton acknowledged that “the loss of one hundred thousand [pairs] of shoes & as many blankets off Wilmington since Sept. has left us in a sad condition in reference to these important articles.” As soon as he could, on January 16, Lawton sent Longstreet 6,400 additional blankets recently arrived in Richmond from Wilmington.104

Despite the government having been repeatedly let down by private contracts, in December the Quartermaster Department entertained a series of massive contract proposals for clothing and blankets. On December 18, J.J. Pollard wrote to the Secretary of War offering to provide 100,000 pairs of blankets, shoes, flannels, and stationary, with delivery to occur between March and July 1864. Lieutenant Colonel Aurelius F. Cone, one of Lawton’s subordinates in Richmond, expressed his support for the contract, but research to date has been unable to identify further information on Pollard, the contract, or whether any goods ever came of it.105