By Austin Williams, 33rd VA Co. H

The following article was published in the inaugural November 1, 2024 issue of the “Living History Gazette.” Read the entire issue here. It is an abbreviated version of the four part article on Confederate blankets available here, with recommendations added specific to the living historian. Anyone interest in further details is recommended to read the full article.

The biggest challenge facing the living historian building a quality Confederate impression is the relative lack of standardization across the Confederate military. Material culture research is essential due to the array of different uniforms and equipment used by southern soldiers. The same dynamic applies to selection of a blanket for your impression. Most Union soldiers carried a wool blanket with relatively standard specifications. The Confederate living historian, however, has a wider variety of different options and it can be difficult to determine which is best suited for your impression without a basic knowledge of Confederate blankets.

British imports dominated the antebellum blanket trade in America. The United States in the mid-1800s produced relatively limited supplies of the coarse wool required for heavy woolen blankets, while British manufacturers had both abundant domestic supply and ready access to cheap wool from Europe. By 1859, England exported over 55 million yards of blankets, heavy woolens, and wool carpets to the United States. Blankets for American markets were often dyed in various shades of deep blue, grey, blue-grey, scarlet, and green, while domestic British consumers preferred undyed white blankets. Blankets were woven as a long continuous piece of heavy fabric and cut down into pairs of blankets for sale, so blanket imports were frequently denoted as pairs of blankets rather than single blankets. Stipes of various widths and contrasting colors both helped to ensure alignment during weaving and denoted where to cut individual blankets.1

All American industry combined produced roughly a million yards of blankets in 1860. Most of this production was from New England and all the southern states combined produced only 1,650 pairs of blankets in 1860. Only a single southern mill, opened by the Crenshaw Woolen Company in Richmond in December 1860, had the extra wide looms required to weave full 60-inch-wide blankets. Many American blankets were constructed of two pieces of narrower heavy woolen fabric, sewn together along a lengthwise center seam.2

When the war began, Crenshaw offered to produce blankets for the Confederate military, but the Quartermaster Department instead signed a contract with Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co., operators of Washington Mill in Fredericksburg, to produce 10,000 Army blankets. Invoices survive for delivery of at least 5,848 blankets between June and October 1861, but it is unclear whether the contract was ever filled in full. The advance of Federal troops in spring 1862 forced Kelly, Tackett, Ford & Co. to relocate their equipment to Manchester, just outside of Richmond. There they were a major cloth supplier but no record exists of further blanket production.3

Crenshaw, their government bid rejected, agreed to produce 5,000 Army blankets for a commercial firm. Throughout fall 1861, the mill produced 450 grey wool blankets weekly, measuring 60 inches by 80 inches and weighting 3 7/8 pounds. The businessman resold the blankets for twice what he had bought them for as the price of increasingly rare blankets skyrocketed by the war’s first winter. Crenshaw sold an additional lot of 1,000 Army blankets in February 1862, but the extent of their blanket production after this is uncertain. The firm signed a large military contract in September 1862 to supply uniform cloth, which ran until the mill’s destruction in a May 1863 fire. Later that year, President Davis was told “we are now destitute of a supply of blankets… there are no factories in the South engaged in the manufacture of blankets. We are dependent almost entirely on purchases in England…”4

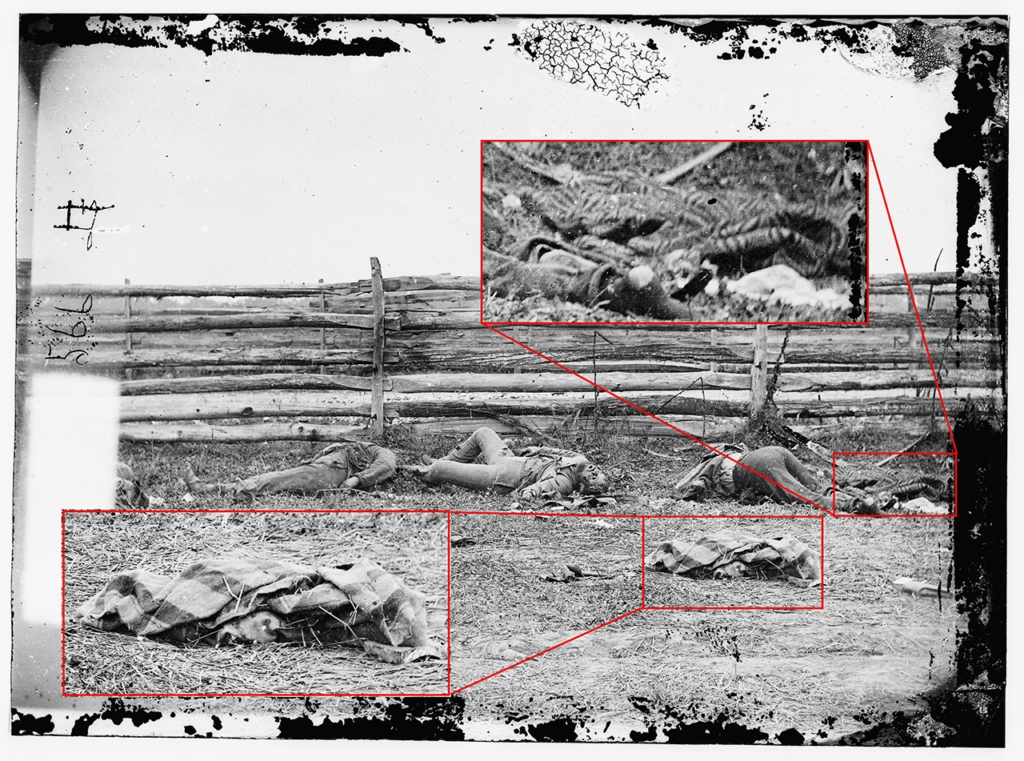

With limited domestic production, the South turned to expedients. Citizens donated large numbers of blankets during each of the war’s first two winters. A South Carolina relief organization called in 1862 for civilians to “contribute liberally… in blankets or woolen carpets as a substitute for blankets. The quilted ‘comforts,’ so called, are not considered so useful to the solider as the blanket, which is easier dried after being wet. Let the ‘comforts,’ then, be retained for use at home, and our blankets be sent to our soldiers.” A patterned civilian coverlet and a likely civilian wool blanket are both visible in one of the photos of Confederate dead at Antietam. The Quartermaster Department paid Crenshaw in October 1862 to scour and clean donated blankets, drawers, quilts, comforts, and bedding. Some of the items cleaned were likely captured Federal equipment being prepared for reissue, as the contract also included dying overcoats, coats, jackets, and pants.5

Among the donations were wool carpets lined with cloth and pressed into service as emergency blankets. Purchases of “carpet blankets” date as early as September 1861. The Nashville Depot reported in January 1862 having used 20,559 yards of carpeting for emergency blankets and contracted with a local firm for 13,041 lined carpet blankets. In the first two years of the war, the North Carolina state quartermaster issued at least 11,952 carpet blankets and in 1863 the Atlanta Depot had 20,559 yards of carpeting on hand for blankets. With even carpets becoming scarce, in 1863 the Georgia state quartermaster manufactured 10,000 blankets out of jean and kersey cloth lined with cotton shirting. Half of these had been issued by October 1864, with 4,895 still on hand.6

While these expedients helped address immediate needs, the Confederacy increasingly turned to England to solve its blanket shortage. 20,000 blankets landed in Savannah aboard the first major blockade runner in September 1861. By circa December 1862, Confederate agent Caleb Huse reported having shipped 62,025 blankets from England. Some shipments were intercepted, like 192 bales of gray blankets “believed to be such as are used in the United States army” found by on the captured steamer Peterhoff. Many more, however, reached the troops, with a soldier in Georgia writing in November 1863: “Quantities of new English blankets have been issued. A single one is large enough to cover a double bed and the texture is far superior to the blankets usually brought south with goods…”7

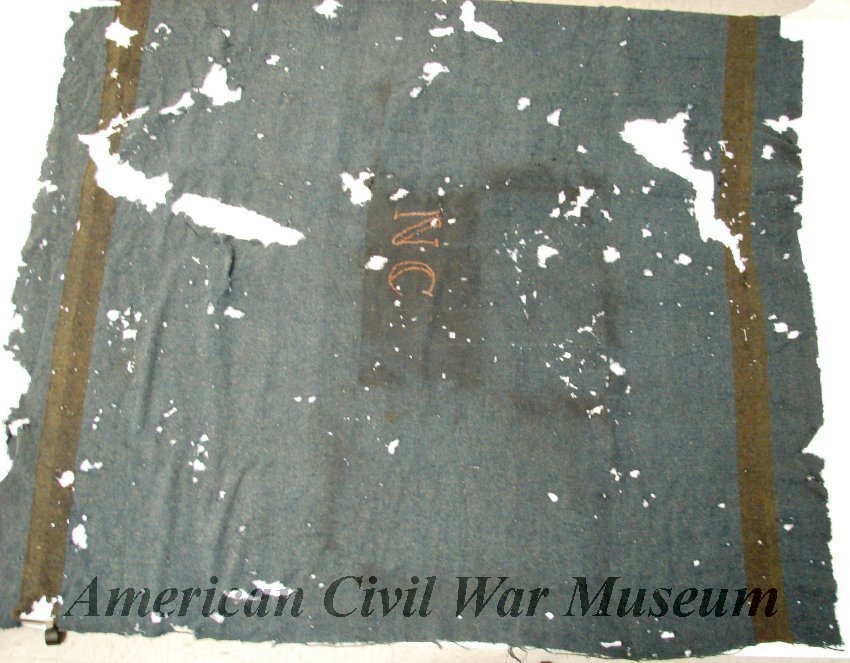

North Carolina uniquely supplied its own troops instead of relying on the central government.Between September 1862 and March 1864, the state issued 33,164 blankets. During the winter of 1862-1863, this number included 2,249 cotton comforts and 1,338 quilts, but these expedients fall away after the state began importing English blankets in 1863. By September 1864, the state had issued 31,000 imported blankets and had 26,886 more on hand. Three of these blankets survive and are nearly identical, with a twill weave of cobalt blue yarn, wide black stipes on each end, and with ‘NC’ embroidered in the middle using red yarn. Georgia followed suit in 1864, importing 113 bales of blankets in early summer 1864. These shipments quickly reached the troops, as a Georgian officer wrote soon after “… I laid under a pine, on a nice pair of new white blankets I had been allowed to buy out of an importation of the blockade by the state of Georgia for Georgia troops.”8

Importation efforts reached impressive heights in 1864. The Quartermaster Department estimated it had imported 316,000 blankets between November 1863 and December 1864. In the final six months of 1864 alone, the Quartermaster Department issued 156,092 blankets, almost certainly all of which had been imported. After shoes, no other quartermaster item was imported in larger numbers than blankets.9

Confederate soldiers huddled for warmth under a wide array of blankets and the period you are portraying dictates the appropriate blanket for your impression. Early war impressions call for coverlets, quilts, and carpet blankets. Imported English wool blankets should predominate mid and late war impressions. Wool blankets of practically any period design and construction are appropriate throughout, reflecting the variety of English blankets in antebellum use, those imported during the conflict, and limited domestic production. Federal blankets are also appropriate, as at least some British imports closely resembled Union blankets and captured blankets were reissued by Confederate authorities (presumably with the ‘US’ removed). With a few portrayal-specific modifications, almost any period blanket is a viable choice for your Confederate impression.

Footnotes

- Frederick J. Glover, “Thomas Cook and the American Blanket Trade in the Nineteenth Century,” Business History Review 35, no. 2 (1961), p. 234-235; Leone Levi, ed., Annals of British Legislation, vol. VIII (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1861), p. 103; Third Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the Best Means of Preventing the Pollution of Rivers, Vol. II (London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1867), p. 88; Jubb, Samuel. The History of the Shoddy Trade: Its Rise, Progress, and Present Position. Houlston and Wright, 1860; p. 52 and 130; Charles Anthony, “English Army Blankets circa 1775-1812,” Military Collector & Historian, Vol. 60, No. 2 (Summer 2008), p. 157.

- United States Census Office, Manufactures of the United States in 1860, Compiled from the Original Returns of the Eighth Census (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865), p. xxii-xxiii and xxv.

- Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1862; Kelly, Tackett Ford and Co., Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Richmond Enquirer, December 30, 1862; Richmond Enquirer, October 17, 1861; Crenshaw and Co and Crenshaw and Woolen Company, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; The Daily Dispatch, February 05, 1862; Speech of Mr. McCue of Augusta Delivered in the House of Delagates on the 16th and 17th October 1863, p. 5.

- Central Association for the Relief of the Soldiers of South Carolina; The plan, and address, adopted by the citizens of Columbia, October 20, 1862, p. 14; Citizen’s File – Crenshaw and Co; for analysis of Crenshaw’s contract to scour and dye clothing and other items, see Richard M. Milstead “Confederate Government Cleaning and Dyeing of Union Clothing in Richmond,” Miliary Collector & Historian – Journal of the Company of Military Historians, Vol. 76, No. 1 (Spring 2024), p. 77-78.

- Christian and Lathrop, Citizens File.; C. L. Webster, Entrepôt: Government Imports into the Confederate States (Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press, 2010), p. 50-51; Lord, J T, Citizens File; “Doc No. 1: Appendix B,” Documents Accompanying the Governor’s Message, Adjutant General’s Report, Dated 15 Nov 1862 (Raleigh: W.W. Holden, 1862); Thomas M. Arliskas, Cadet Gray and Butternut Brown: Notes on Confederate Uniforms (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 2006), p. 75.

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Ser. I, Vol. 6 (Washington: War Records Office, 1897), p. 279; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 4, Vol. 2, (Washington: War Records Office, 1900), p. 383; E. Delafield Smith et al., The British Steam-Ship “Peterhoff” (New York: L.H. Biglow, 1863), p. 51 and 122; Craig L. Barry and David C. Burt, Suppliers to the Confederacy III: British and European Imported Quartermaster Goods, Artillery and Other Ordnance (St. Petersburg, FL: BookLocker.com, 2017), p. 263.

- “Doc No. 1: Appendix A,” Documents Accompanying the Governor’s Message, Adjutant General’s Report, Dated 16 May 1864(Raleigh: Lawrence & Lemay, 1864); Webster, p. 120-121 and 124; Frederick C. Gaede, “Three NC Blankets,” Miliary Collector & Historian – Journal of the Company of Military Historians, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Fall 1989), p. 157-158; Gary W. Gallagher, Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989), p. 445-446.

- Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 930, 955, and 1041.