This is Chapter Two of a four chapter article. See Chapter One, Chapter Three, and Chapter Four. For a brief summary of this article, adapted to address the needs of living historians, see Blankets for Your Confederate Impression published in the ‘Living History Gazette.’

Development of the British Blanket Industry

Confident though Benjamin might have been regarding the prospects of domestic blanket production, it would be impossible for southern industry to come even close to the dominance of British manufacturers. The English blanket trade had its roots deep in the Middle Ages, with small family firms spinning yarn and weaving blankets by hand. During the latter half of the 1700s, these traditional artisans and guilds began to be overshadowed by increasingly larger companies.

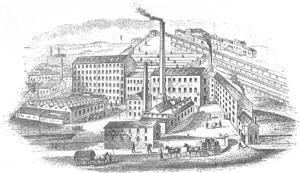

Then, in 1792, merchant-turned-manufacturer Benjamin Gott began a revolution in the industry when he opened England’s first large woolen mill, Bean Ing Mill, in Leeds. The soon famous Bean Ing helped establish Leeds, a city in the northern English region of Yorkshire, as a center of blanket and textile production. This development coincided with the Napoleonic Wars, which, due to the constant demand for blankets and uniform cloth, was “perhaps the most powerful single influence on the woollen cloth industry.” Gott’s firm, Benjamin Gott & Sons, supplied cloth and blankets to the British, Russian, Prussian, and Swedish militaries during the conflicts. He established a second large mill at Armley to meet demand for his products.1

Although Gott and others spurred expanded textile production in Yorkshire, the true center of England’s blanket industry had for centuries been the Oxfordshire town of Witney. The Witney manufacturers held a well-established reputation for high quality, while Yorkshire’s early reputation was for cheap, coarse cloth. The quality of wool used was similar, but the Witney firms used more refined cloth dressing and finishing methods that produced a finer product.2

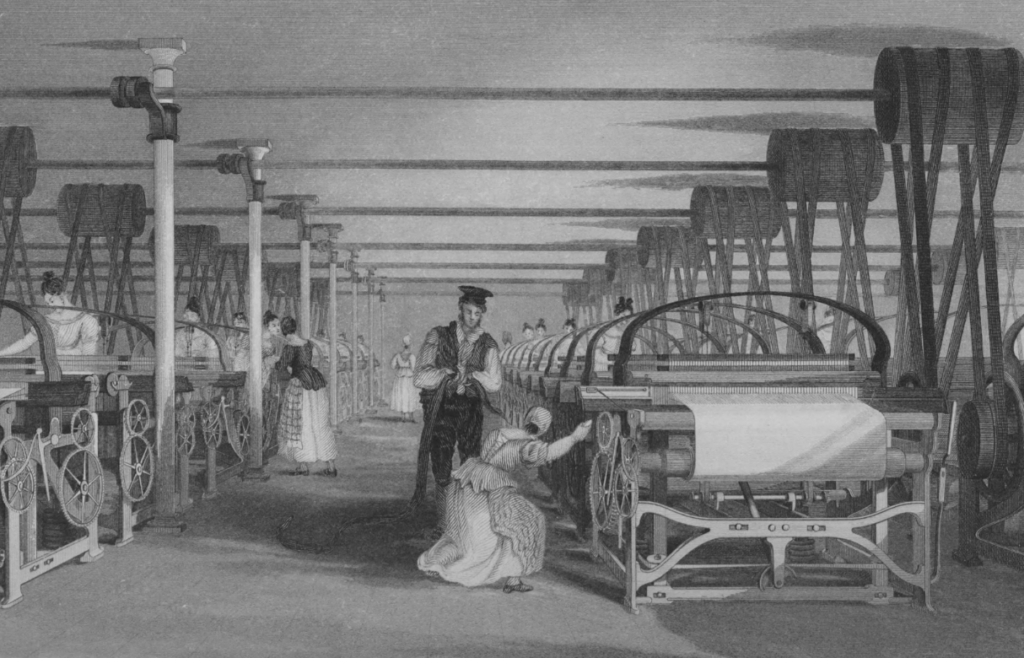

Whether in Witney or Yorkshire, blanket manufacturing in the early 1800s remained rooted in legacy processes, even as early industrialization began to transform the industry. Companies bought raw wool and spun it into yarn at their mills. Yarn was then distributed to local artisans, who worked at home using either their own hand loom or looms owned by the company. The completed blanket would then be returned to the mill for dying and final finishing before it was ready for sale. In the early 1840s, however, incorporation of stronger cotton warps made possible the introduction of power-driven shuttles in Yorkshire. The first of these early power looms was installed in 1844 at Dewsbury Mills.3

Power looms increasingly gave Yorkshire manufacturers an edge over their competitors in Witney. The balance of power in the industry had begun to shift to Yorkshire in the late 1830s and by the 1850s Yorkshire had established a clear lead in the production of heavy woolen fabrics and blankets. It took only a few years for other Yorkshire firms to copy the example of the Dewsbury Mills and install power looms, but the Witney manufacturers would not begin using this technology until the late 1850s.4

Blanket making of the period generally resembled the following process at larger mills using power looms, although many small producers continued to use a blend of legacy methods and new technologies through the Civil War period:

-

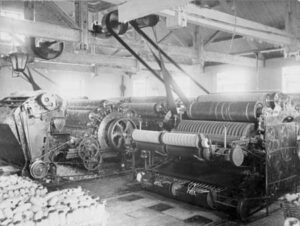

Scribbling and carding machines at a Witney blanket mill in 1898 (Image Credit: Historic England Archive) Wool arrived at mills as bales of raw sheep’s wool, sorted by quality.

- The wool was cleaned to remove grease, dirt, and other impurities. Many manufacturers used scouring machines that bathed the wool in successive rounds of detergent and hot water, followed by a wash in clean cold water.

- After drying, wools of different qualities, lengths, and colors were blended to create the desired grade.

- Wool would then be fed through multiple “willeying” machines that opened up and pulled apart the wool fibers. The first, a “shake willey” shook the wool while cylinders with metal spikes beat and roughly opened the wool. Then the wool was fed through a “teaser” which had cylinders of finer teeth that further opened the wool fibers.

- Olive oil was sprinkled on the wool fibers to lubricate them prior to carding.

- Wool began the carding process by passing through a “scribbler,” a machine with a large roller covered with a leather sheet with embedded bent steel wires. The wires graduated from coarse to fine to further disentangle the wool and draw out the fibers.

- After being roughly carded on the scribbler, the wool was fed into a fine carding engine with even finer teeth than the scribbler. These teeth more perfectly opened the wool and spread it into a regular thickness and weight. The output was a light, filmy substance of cardings about three feet long.

- The carded wool was then “slubbed” on a frame called a “billy,” which generally contained 60 spindles, to join the cardings together into continuous “silvers”. In the 1850s, a new machine was introduced in this portion of the process called a condenser, which used a “ring doffer” of bands of wire teeth to condense the carded wool into narrow strips which were then rubbed between leather belts to form silvers. Silvers were wound on long woolen bobbins for spinning.

- The large bobbins of silvers were placed in a row along the back of the spinning mule, a fixed frame holding the bobbins and a moving carriage with between 300 and 1,000 spindles holding small bobbins on which the yarn would be spun. The carriage moved on rails to stretch the yarn while the small bobbins rotated to twist the yarn. The carriage was then reversed to wind the yarn on the bobbins, repeating the process until the bobbins were full.

- Dying could occur at various points in the process, but dyeing yarn at this stage was common. Most blanket produced for British markets were left undyed and bleached white, while blankets for export markets were often dyed.

- The thread running the length of the blanket, around which the yarn would be woven, was called the “warp.” Warp threads had to be measured to the correct length and wound onto warp beams that were then attached to the back of the loom.

- Bobbins of yarn were placed on a flying shuttle, a wooden boat-shaped object with metal ends. One set of warp threads were raised, and the shuttle was sent flying between the warp threads to the other side of the loom. The alternate warps were then raised and the shuttle sent flying back in the opposite direction. This process continued with the “weft” yarn being woven between the warp threads. Once a blanket’s length of material had been woven, it was common to switch to an alternative color yarn and weave in colored stripes called “laces” or “header bars.” These stripes marked the places where the fabric would be cut into individual blankets. The process was continued until a complete “stockful”, or a continuous piece of blanketing material usually about 24 blankets long, had been woven. At this stage the material remained coarse and appeared more like rough sacking than a blanket.

- The stockfuls were next “fulled” to remove grease and shrink the material to size, drawing the fibers closer together into a thicker and softer material. The material was soaked in soap and water to clean and soften the wool. It was then run through a milling machine or fulling stocks. Stockfuls were fed into the milling machine and then ends were sewn together to form a continuous loop. The loop of material was run between rollers until it had shrunk to size. The older fulling stocks method used a machine with large wooden hammers to pound and roll the fabric to make it shrink and drive out dirt.

- The material was washed in water to remove the fulling soap and then dried outside on long tenter racks or dried indoors via steam.

Stockful of wool blankets being stretched on a tenter rack to dry. Note the header bars to denote each individual blanket.(Image Credit: Historic England Archive) - White blankets were then bleached in long, airtight buildings by burning sulfur underneath the lengths of stockfuls hung from rails in the roof. This process gave the blankets a strong, lasting smell and so some blankets were made unbleached. These blankets were cleaned with fuller’s earth instead of soap and were only bleached via natural sunlight.

- The material at this point was clean and dry, but hard and heavy. A “raising machine” raised the nap of the fabric and produced a soft, fleecy finish by using cylinders covered with fine steel wires.

- Finally, the stockfuls were cut into individual or, more commonly, pairs of blankets and packed tightly into bales for shipping.5

The British Blanket Industry on the Eve of War

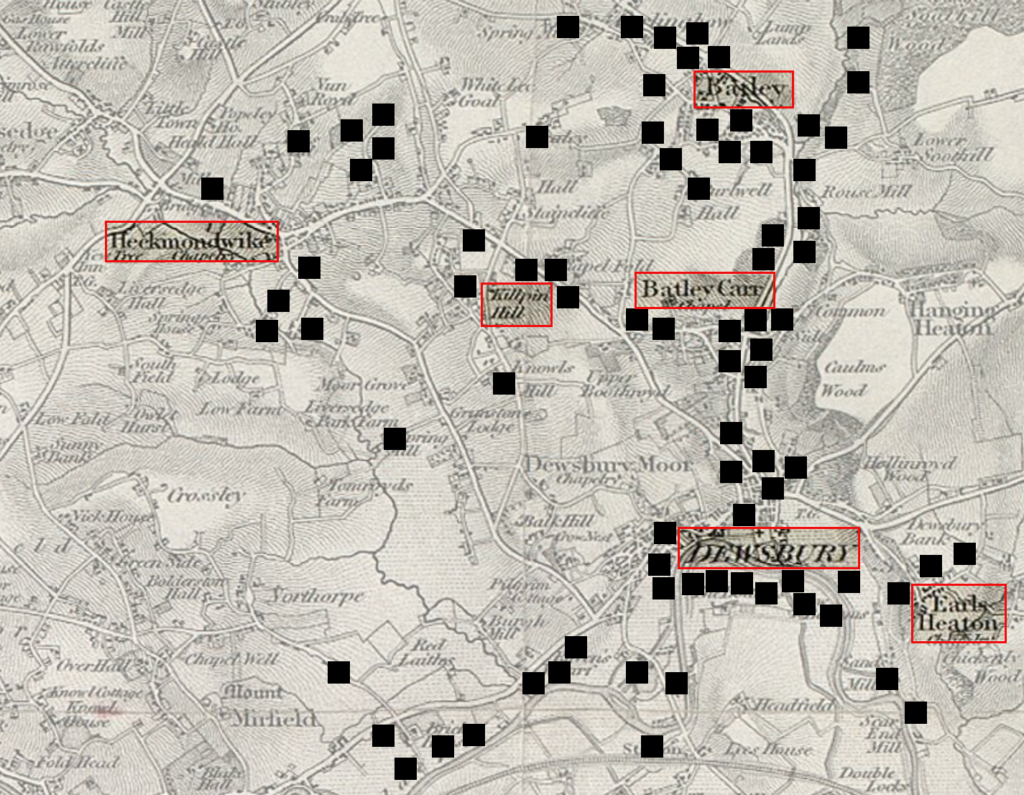

As war loomed in America, the manufacture of blankets in England was largely concentrated in a few towns in the West Riding District of Yorkshire. According to the 1861 British census, 72% of the woolen textile workers in England and Wales resided in Yorkshire. Blanket manufacturing in particular was concentrated in the “Heavy Woolen District” between the West Riding towns of Dewsbury, Batley and Heckmondwike. The area had long hosted many small companies, perhaps only a single family, utilizing hand looms to make blankets. Beginning in the early 1840s, however, increased use of power looms forced consolidation of many of the smaller firms. By 1860, roughly 11,000 people in Yorkshire were employed at steam-powered mills, while another 2,000 weavers still operated hand looms to produce blankets and other heavy woolens. By 1864, 166 different blanket manufacturers operated in the Heavy Woolen District. The majority of these remained exceedingly small, with only a few companies of substantial size. A senior partner of one of the large firms observed “this neighborhood is studded with multitudes of small makers whose whole property may not, nor does, average £100…”6

Merchant houses in Leeds, the major West Riding city roughly ten miles northeast of the Heavy Woolen District, purchased the output of many of these smaller firms. These blankets would be bought unfinished, with dying and other finishing work conducted in Leeds prior to sale for either the domestic or export markets. The biggest of these merchant firms on the eve of the Civil War remained Benjamin Gott & Sons, which both purchased blankets from Yorkshire makers and manufactured blankets and cloth themselves. The firm was one of England’s largest employers in the early 1800s and at the start of the Civil War, Benjamin Gott & Sons employed 291 men, 361 women, 63 boys, and 102 girls in several mills. Over 500 worked at the Bean Ing Mill alone. Contrast that workforce with the circa 60 men and women employed by the Confederacy’s Washington Woolen Mill.7

A circa 1860 visitor to the Bean Ing Mill wrote “we observed, in all its stages, cloth sufficient, one would imagine, to clothe the world for many years to come, and that too of every shade of colour and gradation of price.” Gott’s operation was massive and relied heavily on the latest in industrial technology. The same visitor, writing of the sense of wonder he felt touring the Mill, stated “how will that wonder be increased when he passes into another room, running the whole length of one portion of the building, containing mules over 100 feet long, each having 600 spindles and guided by only one man and two girls!”8

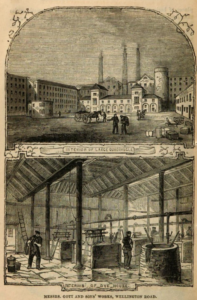

The largest of the blanket manufactures in the Heavy Woolen District itself was Cook, Son & Wormald of Dewsbury. Originally founded as Hague & Cook in 1811 as a woolen spinning and cloth fulling business, in 1815 they began weaving blankets and heavy woolens at their Dewsbury Mills two miles south of Dewsbury. Guided primarily by senior partner Thomas Cook, the firm steadily expanded as Hague, Cook, & Wormald throughout the 1800s on the strength of their export trade to the United States and their success winning major government contracts. By the mid-1800s, Hague, Cook, & Wormald was at least three times as large as the next largest of the Heavy Woolen District firms, with Gott and the Witney blanket makers their primary competitors. Around 1859, the company became Cook, Son & Wormald. The firm’s main spinning mill was destroyed by fire in early 1860, but a replacement was operational by summer 1861, just in time to support increased orders from the American conflict. As of June 1862, the Dewsbury Mills operated 5,746 spindles, 161 hand looms (133 leased out to weavers who operated the looms at home), and 124 power looms. To again illustrate the contrast with Confederate domestic production, recall that the Washington Woolen Mill boasted only 37 looms and 1,000 spindles.9

The town of Dewsbury hosted an additional 31 blanket manufacturers as of 1864. The largest after Cook, Son, & Wormald was Thomas Spedding. Until the 1830s, Halliley, Brook & Co. had operated the large Aldams Mill in Dewsbury. After their business failed, Hague, Cook, & Wormald leased the mill for a few years. By the late 1840s, however, local blanket maker Spedding had joined with Mark Newsome and Edward Hemingway to operate the Mill. The description of the Mill, called “one of the most complete Woollen Manufactories in the North of England,” when it was for sale in 1840 gives a sense of the scale of even a moderately sized British manufacture like Spedding compared to the modest facilities of Confederate mills like Washington Mill and Crenshaw Mill:

“All that extensive Carding, Scribbling, and Fulling Mill, called Aldams Mill, consisting of a Mill, sixty yards long by thirteen yards wide, and three stores high – with Counting House, three large Warehouses, Press Shops, Wool Chambers, Weaving Shops, lighted with Gas and heated by Steam, Wool and Piece drying house, heated by steam, Dyeing house, cistern, Gas House, Steam Engine of fifty horse power, with boilers, shafts and going gear, five Willies, Fourteen Scribblers, Six single and five double Carders, Fourteen Billies, Two Tommies, Two Mules, three Raising Gigs, Ten Fulling Stocks, Three Rag Machines and one Washing Machine, and other machinery…”10

Just north of Dewsbury, in the hamlet of Batley Carr, was another moderately sized firm, Joshua Ellis & Sons. Previously James Ellis & Sons, Joshua had taken sole ownership of the firm from his father in 1843. In the mid-1860s, his brother and partner Robert Ellis served as mayor of Dewsbury. The firm operated two mills and employed 500 people.11

Contiguous with Dewsbury and just to the south was the village of Earlsheaton. On the eve of the Civil War, there were five or six blanket mills in the town and a significant proportion of the population was engaged in making white and colored blankets, including gentian (a rich blue), scarlet, and green. The village, which continued to favor traditional hand looms over power looms, specialized in weaving and utilized yarns spun in mills elsewhere in the district. From time-to-time makers in Earlsheaton worked together to execute large orders for all-wool blankets for the British government. The Earlsheaton area had 43 different blanket manufacturers as of 1864, of which some of the largest were Thomas Tong, Edward Hemingway, Less, and Towson.12

Two miles northwest of Dewsbury was the thriving town of Heckmondwike. For decades, the village had hosted blanket sales on Mondays and Thursdays at the town’s Blanket Hall. “The chief article of manufacture is that of blankets, in all their variety of quality, size, style, colour, &c.” wrote a member of the local textile trade in 1860. “White wool blankets, of superior quality, are made here and in the immediate neighbourhood in quantity; and indeed Heckmondwike may be designated the head quarters of the blanket trade.” The countryside surrounding Heckmondwike hosted several small blanket makers and “if one happens to be in the neighbourhood, on a fine sunny day, the hills may be seen dressed out in snow-white drapery (blankets), forming a pleasing scene, and one bespeaking well-directed industry.”13

The village had 44 active blanket manufacturers as of 1864, but the largest was Edwin Firth & Co., a company that, like Thomas Spedding, inhabited the tier of manufacturers below Cook, Son, & Wormald. A successful merchant, Firth bought Flush Mills in Heckmondwike when it came up for sale and began manufacturing blankets. As his five sons came of age, he brought them into the firm. Their products were woven by hand, usually in the homes of their employed weavers. The mill burned down in 1858 after a bit of steel was accidentally fed into a machine with the wool, struck a component, and created a spark. Flush Mills was, however, soon rebuilt and was operational during the Civil War period.14

Just outside of Heckmondwike along the Halifax Road to Dewsbury lay another concentration of blanket makers in the village of Kilpin Hill. Although small, by the eve of the Civil War there were 12 blanket manufacturers in the hamlet. The largest of these companies were all owed by sons of Joseph Tatterfield, previously the most prominent of the Kilpin Hill manufacturers. These included Jeremiah Tattersfield & Sons, George Tattersfield & Co., Moor End Mills, John Tattersfield & Sons, and Tattersfield, Oddy & Co. The first three of these employed only 15-30 people. The brothers, however, would collaborate on larger orders and, together, they stood along Edwin Firth & Co. and Thomas Spedding as the three largest blanket makers in the region in the tier below the massive Cook, Son, & Wormald.15

East of Heckmondwike is the town of Batley, of which more will be said later. As of 1864, the town had 47 blanket makers. Foremost among them were George Sheard and John Nussey. Nussy operated Carlinghow New Mill and, while much smaller, was one of the competitors of Cook, Son, & Wormald. Sheard was one of several smaller manufacturers from whom Cook, Son, & Wormald would occasionally obtained goods when required to fill larger contracts that exceeded their own capacity.16

Meanwhile, the blanket trade in Witney continued to struggle to compete against their Yorkshire rivals. Throughout the 1850s Witney lacked the railroad connections Yorkshire boasted, making it more difficult to obtain coal and delaying the widespread adoption of steam power in Witney. Yorkshire’s greater use of machinery produced blankets that the Witney firms viewed as being “of inferior quality, and at lower prices,” undercutting the Witney makers’ reliance on their reputation for high quality goods. Blanket makers made up 19% of the town’s population in 1851, the single most common occupation. The Witney population declined throughout the 1850s, while Yorkshire’s population boomed.17

The same process of consolidation that occurred in Yorkshire was reflected in Witney as well, with a few dominant firms rather than the previous large number of independent master weavers. By the 1850s, only six notable companies remained in operation and consumed only about 28,800 pounds of wool weekly. These firms largely survived based on their existing reputation and major contracts they held with London merchants and the Hudson Bay Company.18

The largest of the Witney firms was Edward Early & Son, employing up to 800 people in the decade prior to the Civil War. The next largest was John and Charles Early & Co, employing around 300 people, followed by Richard Early, Richard Early Jr., and Horatio Collier. Despite the family ties between these companies, relations were not always cordial. In the late 1850s, an attempt by Edward Early & Son to break into the lucrative Hudson Bay Company trade caused bad blood with John and Charles Early & Co. In 1859, Edward Early & Son’s notepaper warned they had “no connection with any other Firm by the name of Early.” The tensions eased, however, in 1860 after Edward was placed on the Hudson Bay Company’s list of blanket contractors.19

John Early & Sons had been one of the leading Witney firms in the first portion of the 1800s, operating 70 looms at a time when most other companies had only 20-35. The firm became John and Charles Early & Co. in 1851 after John brought his son Charles on as a partner. The company had, around that time, 144 employees, including 16 women and 28 children. Charles embraced new technology in a way other Witney firms had not. He installed the first power spinning mule in the firm’s New Mill in 1853, introduced power looms in 1858, and in 1861 added a steam engine at New Mill. Possibly more critically, in 1861, Charles helped open a rail connection to Witney. After John’s death in 1862, the firm became known as Charles Early & Co. by 1864.20

Edward Early & Son operated a factory at West End and continued to rely on handlooms to produce blankets. They leased a second facility, Farm Mill, from the 1840s through the 1860s. Possibly due to their delayed embrace of industrial processes, however, they were ultimately bought out by Charles Early & Co. two decades after the Civil War. The Collier family was the second most prominent of the Witney blanket families, with Horatio Collier making blankets at the Corn Street Factory and Crawley Mill.21

The leading British blanket manufacturers available to fulfill Confederate orders during the Civil War are perhaps best summarized by the entrants in the 1862 International Exhibition in London. Among the firms displaying goods in the Industrial Department of the Exhibition were:

- Benjamin Gott & Sons, Leeds: Cloths, blankets, and woolen yarns.

- Thomas Cook, Son, & Wormald, Dewbury: Blankets, rugs, and cloths. Awarded a medal “for superior blankets at low prices.”

- Edwin Firth & Sons, Heckmondwike: Blankets, cloths, sealskins, mohairs, rugs, &c. Awarded a medal “For superior sealskin cloakings, also blankets for cheapness.”

- John Early & Co., Witney: Blankets, pilot and collar cloths, and tweeds

- Edward Early & Son, Witney: Witney blankets, tilting, yarns, rugging. Awarded a medal “For very superior Witney blankets.”

- Horatio Collier, Witney: Witney blankets22

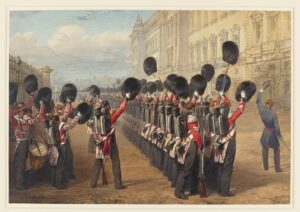

A Very Fit and Proper Pattern for the Service – British Army Blankets

Many of these firms, in addition to producing blankets for civilian use, also worked under contract for the British government to manufacture army blankets. Although the British blanket trade overall was highly competitive in the 1800s, supplying blankets and heavy woolens for the British military was oligopolistic. Only a small number of companies regularly took on the risks and profits associated with British government contracts. In the early decades, the Witney manufacturers and Benjamin Gott & Sons received most of the contracts. Witney firms like John Early & Sons had established relationships with the British Board of Ordnance and greater experience efficiently adhering to promised delivery dates. The Witney focus on British government contracts may have, in part, allowed the Yorkshire producers to capture most of the American export market in this period, as will be described in a following section.23

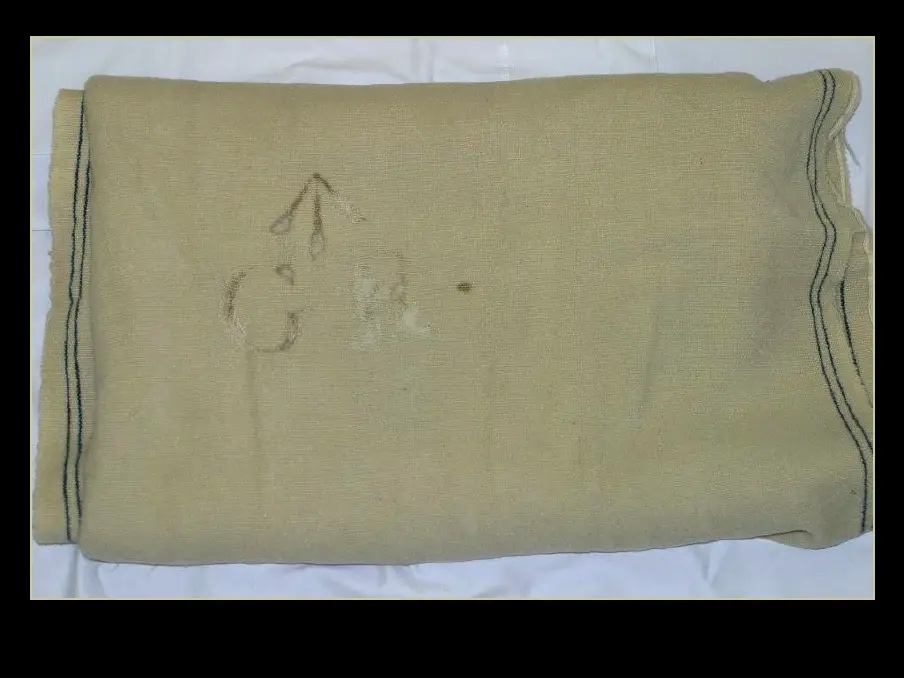

The blankets made by Witney for the British Army in the late 1700s and early 1800s were natural white wool. At least eight of these white blankets survive in American museums with provenance from the American Revolution and War of 1812; oddly enough, no surviving blankets from this period have been identified outside of the Americas. British Army regulations from circa 1803 stipulated blankets were to “measure when furnished 84” long by 66” wide and to weigh when perfectly dry and free from oil or filth of any kind 8lbs and 6oz per pair. The warp and wool alike and not spun to[o] hard and thready. The knap well raised on both sides, the colour clear and good and the wool itself good and sweet….”24

Surviving blankets from this period are all stamped with a roughly 4.5-inch-tall broad arrow and GR (for Georgius Rex, i.e. King George) of roughly the same size, which marked them as official Army property. An 1814 contract for the British Army in Canada ordered 40,000 blankets measuring 72 inches wide and 90 inches long, “to be stamped each with durable marking stuff (G.R.) in each corner.” These marking were not unique to blankets and could be found on British army shirts, knapsacks, and other official property. By the 1860s, the mark had evolved from the king’s initials to WD for War Department.25

The blankets all have stripes or “header bars” that, as noted above, marked where to cut between individual blankets and also helped the weaver control the shape of the blanket. The stripes on these blankets were very narrow, only two shots of colored yarn followed by 4 shots of white yarn followed by another two shots of colored. These vary from 1-3 inches from the end of the blanket. The variance may be due to lack of precision in cutting as well as fraying over time, as the ends of the blankets were not bound or finished in any way. Stripes on some surviving blankets are medium to dark brown, likely having faded from black. Other blankets have blue stripes and it remains unclear whether the color difference is significant or was simply a detail left to the discretion of the contractor.26

Several, but not all the blankets have two small hash marks of colored yarn along the selvage. These are likely a style of point mark, a system used to denote the size of a blanket with more points meaning a larger blanket. Some of the blankets have these hash marks in the same color as the stripe, others have them in a yellow or gold color.27

The size of these blankets is difficult to define. As noted above, an 1814 contract specified 72 inches wide and 90 inches long, but the British military ordered blankets in a variety of sizes for different purpose, such as for use in barracks versus use on campaign. The surviving blankets vary from 60 to 72 inches wide and from 75.5 to 90 inches long. Their weights range from 3 pounds 12 ounces to 4 pounds 13 ounces.28

Hagues, Cook, & Wormald received their first major government contract, possibly for blankets like these, in 1823 to supply 22,000 blankets. Between then and 1850, the firm fulfilled 91 different contracts with the British military and supplied 1,323,000 blankets and 421,000 yards of cloth. Throughout the early-to-mid 1800s, roughly 20 companies competed for these lucrative contracts. Six of these were Witney firms like John Early & Sons. Five were London firms, like Hebbert & Co., S. Issac Campbell & Co., and Dolan & Co., that did not themselves produce blankets, but subcontracted for blankets from Witney and Yorkshire manufacturers. The rest of the companies were all in Yorkshire, including Hagues, Cook, & Wormald, Benjamin Gott & Sons, and Edwin Firth & Co. Although competitors, several of these companies also colluded on government contracts, agreeing not to underbid each other and dividing up portions of contracts amongst themselves.29

Between the 1820s and 1850s, the British government purchased army blankets in the following standard sizes:30

| Type | Size | Weight |

| Barracks | 56 inches by 93 inches | 8 lbs |

| Hospital | 56 inches by 96 inches | 4 lbs 12oz |

| Single | 56 inches by 92 inches | 3 lbs 12 oz |

| Coverlets | 51 inches by 36 inches | 4 lbs |

The Crimean War from 1853 to 1856 caused a spike in demand. The British government alone required 300,000 additional blankets and British allies also looked to English mills to produce blankets for their troops. Firms like Edwin Firth & Co. “threw themselves heartily and successfully into the large business to be done in the supply of army cloths and blankets.” They became the exclusive English contractor supplying blankets for the French military. In the 1860s, a representative of the firm testified that they made “blankets and woollen cloths for army purposes chiefly.”31

It is unclear exactly when the British Army transitioned away from white blankets. There are references to Crimean War era blankets being “buff colored with a red stripe.” Following the conflict, however, references to other colors begin making appearances. A merchant who purchased surplus military equipment to resell stated in 1858 that “I have got now 700-800 new brown blankets, sold at the last Tower sale, and they are all of them stamped.” The War Department put out a request for contract proposals that same year for 10,000 grey blankets, “specifications state that no shoddy, woollen waste, hair, or anything else but pure wool should be used, and that no soap, stoving, or dry raising, in getting up there [sic] goods shall be allowed.”32

The contract for these blankets went to Haigh, Cook, & Wormald and the surrounding circumstances illustrate the sometimes questionable practices connected with these deals. The War Department provided Charles Elliott, Superintendent of Inspectors at the Tower of London, with the contract specifications above as well as a model pattern. Elliott noted, however, that the pattern contained impurities, contrary to the specifications calling for nothing but pure wool. He employed London broker Jeremiah Carter Jr. to provide alternative samples. Carter had inherited his business from his father, who had been the London agent for Haigh, Cook, & Wormald and was a key player in the firm’s collusion with other companies seeking government contracts. The family firm continued to represent Haigh, Cook, & Wormald until the 1880s. Both father and son were repeatedly accused of having an inappropriately close personal relationship with the Tower inspectors like Elliott.33

Carter brought Elliott six blankets. “The one selected,” testified Elliott, “as considered to be perfectly in accordance with the specification, and a very fit and proper pattern for the service, light, warm, and durable.” Carter noted “I gave him [Elliott] the name of the manufacturers of the blankets, and that eventually approved was made by Haigh, Cook, and Wormald, the best manufacturers in the country.” Given the potential conflicts of interest at play, it is no wonder that, around this same time, Thomas Cook testified that for the last 30 or 40 years his firm “have been large contractors with the Government for the article of blankets…. Our business with the Government in the way of blankets has been very large.”34

While grey blankets may have begun to enter service in the late 1850s, by 1861 regulations formally specified a grey blanket for soldiers of both Line and Rifle regiments, making stockpiles of now outdated white blankets potential surplus. As of late 1857, the British government had 159,134 blankets in storage at the Tower of London. In 1863, the British Army offered a contract for 20,000 barracks blankets, measuring 56 inches by 92 inches and weighing 4 pounds 4 ounces each. The contract stipulated the blankets needed to be “Grey color, free from hair and wool waste and perfectly dry, not soaped or dry-raised… one fast, Blue bar [stripe] not more than four or less than three inches from the end.“ British Army regulations by 1865 dictated a grey blanket for field service measuring 60 inches by 86 inches.35

Two original Confederate blankets, held in a private collection and discussed in Craig Barry and David Burt’s Suppliers to the Confederacy Volume III, are nearly identical to the white British blankets from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 periods. The first blanket has two blue stripes on both ends and a small 1 3/4-inch-long sky-blue hash. It measures 62 inches wide by 76 inches long. The other blanket is also white but has two brown stripes instead of blue. It has a matching brown two-inch-long hash mark and measures 68 inches wide by 77 inches long. Neither is marked with a broad arrow or the WD that would be found on British Army property of the period. There are several potential explanations for this lack of marking. It is possible they were made for the British army, failed to pass the rigorous inspection criteria, and were sold as surplus. It is also possible they were copies of the British Army blanket made for sale to the burgeoning British volunteer movement of the late 1850s. Either way, they, and many similar British Army blankets, found their way across the Atlantic and into the hands of Confederate soldiers.36

An Immoderate Demand for Goods – British Blanket Exports to America

These army blankets were only the latest in a decades-long flow of British blankets into America. Following the War of 1812 and normalized relations between England and the United States, British blanket manufacturers were well positioned meet the demand for inexpensive, low-quality blankets demanded by American consumers. Thomas Cook made a major bid in the 1820s for Hagues, Cook, & Wormald to expand into American markets and by the 1830s the firm had become the principal exporter of blankets to the United States. In 1839, Hagues, Cook, & Wormald began selling British Army model blankets to the American government and within six years the firm had taken most of this trade from Benjamin Gott & Sons. At the dawn of the 1850s, American orders for blankets from Hagues, Cook, & Wormald were increasing steadily each year.37

English consumers evidently preferred white or undyed blankets, as British manufacturers made dyed blankets almost exclusively for export to the United States and other overseas markets. At the 1851 British Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, Edwin Firth & Sons received a medal “For blankets with cotton warp, with good workmanship and cheapness combined. This is a new article of produce, and it has become a great branch of trade to the slave states of America.” Hagues, Cook, & Wormald was awarded for a variety of blankets, including “scarlet and blue blankets, for the American trade.”38

In 1860, England exported 5.8 million yards of blankets to the United States, down from the peak of 6.7 million yards in 1852. Manufacturers, particularly in Dewsbury and Earlsheaton, were making an array of gentian (deep blue), grey, blue-grey, and green blankets in various sizes and qualities for American consumers. Their cheapest product was a very inferior grey blanket. An English blanket maker in 1860 noted that “the bulk of these blankets is consumed in the Slave States of American, and the low grey blankets just adverted to are designed chiefly for the use of the slaves.39

The start of the Civil War found the blanket industry in the midst of a slight depression, exacerbated by high wool prices. Initially demand increased only slightly, but realization that the war would last into the winter triggered a surge in demand for blankets and other heavy woolens. In October 1861, the American Vice Consul in Liverpool reported “I am informed that large orders for blankets for the south are being executed in Yorkshire.” The following month, Thomas Cook wrote to his agent in New York, “There is an immoderate demand for goods throughout this district, particularly for Brown, Grey, Army Blankets…”40

During the Crimean War the decade before, the British heavy woolen sector had refined its ability to quickly shift production from civilian products in response to large military orders from British, French, and Turkish forces. They now did so again as military orders began to pour in from the Americas. Mills that had only recently completed a large order of “Blue Mixture” heavy woolen cloth for the Italian Army in 1860 and 1861 adjusted only slightly to begin producing the cadet grey woolen cloth requested by the Confederacy. To meet blanket orders that exceeded their capacity, Cook, Son, & Wormald purchased blankets made by George Sheard in Batley and other smaller manufacturers. As demand increased, so too did the price of blankets, ending the year 40% higher. In December Cook again wrote “Regarding the U.S. Grey Blankets… of which so many are being made at 66 inches by 84 inches, 10 lbs. per pair… we should like to enter into arrangements to commence in January… provided other orders do not come in the meantime… we could deliver 20,000 pairs per month… Our price today would be 14s.2p. per pair… what the price may reach it is impossible to foresee.”41

British blanket exports to the United States and Confederacy in 1861 had been 5.2 million yards. Initially bright prospects for 1862, however, dimmed as the United States passed increasingly more severe tariffs to protect the rapidly expanding New England woolen industry and raise money for the war effort. These laws, beginning with the Morrill Tarif of 1861, would eventually doom the British blanket trade with the United States, but the war boom delayed this by several years. Early in 1862, a Federal prohibition on foreign purchases left Cook, Son, & Wormald with 12,000 yards of contracted fabric on hand. One of the partners visited New York to ensure the firm was paid for the remainder of the contract and Cook mused “This ruinous affair will be a caution to us against entering on a large order for a new make of goods in an excited market and with a limited time.”42

Regardless of the prohibition, some Dewsbury firms continued to make blankets in 1862 for the United States government. “Business in this district has become exceedingly brisk and very large quantities of heavy, grey blankets are being made, many on speculation,” wrote Cook in October, “We however are determined not to meddle with anything we do not get passed and paid for here.” While export numbers are not available for 1862, the following year 2.6 million yards of blankets were exported to the Americas and another 2.8 million yards in 1864. Much of this was likely driven by growing Confederate demand, as Union protectionist policies limited orders for the north. Thomas Cook, whose firm had a decades-long history of selling blankets to the United States Army and strong commercial ties to the north and who thus may have hesitated to contract directly with Confederate buyers, noted Cook, Son, & Wormald had received no orders for grey army blankets in 1863, “whereas during the last two autumns we have been busily engaged in them.”43

The diary of Thomas Jubb records the efforts of British heavy woolen manufacturers to meet Confederate cloth and blanket demand. He wrote on April 21, 1863 that his brother’s firm, John Jubb & Sons of New Ing Mills in Battley had “received orders for about 10,000 yards Blue Mixt. Army’s [cloth] for quick delivery[,] supposed for the Southerners.” The following month he noted “Very busy making Blue Mixt. Army Clo[th]s.” As fall approached, Jubb recounted how blankets “in Mixt. And Blue and Black have a great demand.”44

Go to Chapter Three

Footnotes

- “Benjamin Gott: Captain of Industry,” The Yorkshire Post, May 29, 2018; Eveligh Bradford, “Benjamin Gott,” The Historical Society for Leeds and District, Jan 2015, https://www.thoresby.org.uk/content/people/gott.php; H. Heaton, “Benjamin Gott and the Industrial Revolution in Yorkshire,” The Economic History Review, Vol. 3, No. 1 (1931), p. 46 and 54.

- “Witney History,” Witney.net, https://www.witney.net/history.htm; Heaton, p. 50.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 228 and 240-241.

- Frederick J. Glover, “Government Contracting, Competition, and Growth in the Heavy Woollen Industry,” The Economic History Review, Vol. 16, No. 3 (1964), p. 495.

- “Making a Blanket – 19th Century,” Witney Blanket Story, http://www.witneyblanketstory.org.uk/WBP.asp?navigationPage=Processes+19th+century; Treatise on Mills and Mill Work: On Machinery of Transmission and the Construction and Arrangement of Mills (London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1863), p. 264-265.

- W. Walker Hanlon, “Temporary Shocks and Persistent Effects in Urban Economies: Evidence from British Cities after the U.S. Civil War,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 99, No. 1 (2017), p. 6; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 572 and 575; George S. Measom, The Official Illustrated Guide to the London and North-Western Railway: Including All the Branch Lines and Continuations(London: H. G. Collins, 1850s), p. 103.

- Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 576; The Yorkshire Post, 29 May 2018; “1861 Census for William Gott, at Armley House, Leeds,” Ancestry.com; Measom, p. 105.

- Measom, p. 105.

- Glover, Government Contracting, p. 478-479 and 484; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 460, 493, and 651-652.

- Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 440, 443, and 572-573; The London Gazette, October 25, 1850.

- Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 573; Royal Commission on Water Supply: Minutes of Evidence Taken Before the Commission (London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1869), p. 76; The London Gazette, May 19, 1843.

- Samuel Jubb, The History of the Shoddy Trade: Its Rise, Progress, and Present Position (London: Houlston and Wright, 1860), p. 130; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 572-573.

- Jubb, p. 131-132.

- Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 572-573; Frank Peel, Spen Valley, Past and Present (Heckmondwike: Senior and Co., 1893), p. 214; The Engineer, February 26, 1858.

- “The Tattersfields of Kilpin Hill,” Tattersfield: The Tattersfield One-Name Study, https://tattersfield.one-name.net/?page_id=68; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 573.

- Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 572-573 and 724; John C. Malin, “The West Riding Recovered Wool Industry, ca. 1813-1939” (PhD dissertation, University of York, 1979), p. 400.

- A P Baggs, Eleanor Chance, Christina Colvin, et al., ‘Witney Borough: Economic History, the Industrial Revolution in Witney c.1800-1900,” A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 14, Bampton Hundred (Part Two) (London: Victoria County History, 2004); Roger Lascalles, Lascelles and Co.’s Directory and Gazetteer of the County of Oxford (Oxfordshire: Lascelles & Company, 1853), p. 197.

- Baggs, et al.

- Lascalles, p. 197 and 213; Alfred Plummer, The Blanket Makers, 1669-1969: A History of Charles Early & Marriott (Witney) Ltd (London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1969), p. 96.

- Glover, Government Contracting, p. 480; Plummer, p. 96-97; Baggs, et al.; “Early’s,” Witney Blanket Story, http://www.witneyblanketstory.org.uk/WBP.asp?navigationPage=Manufacturers&file=WBPPERS.XML&record=Early; “Witney History,” Witney.net, https://www.witney.net/history.htm.

- “Early’s,” Witney Blanket Story; “Collier,” Witney Blanket Story, http://witneyblanketstory.org.uk/WBP.asp?navigationPage=Manufacturers&file=WBPPERS.XML&record=Collier; “Witney History,” Witney.net, https://www.witney.net/history.htm.

- The International Exhibition of 1862: Official Catalogue of the Industrial Department, Vol. II (London: Truscott, Son, & Simmons, 1862), p. 64-65; The International Exhibition of 1862: Medals and Honourable Mentions Awarded by the International Juries (London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1862), p. 248.

- Glover, Government Contracting, p. 478-479 and 481.

- Robert G. Stone, “British Military Blankets, 1776-1813,” Military Collector & Historian, Vol. 49, No. 1 (Spring 1997), p. 38; Charles Anthony, “English Army Blankets circa 1775-1812,” Military Collector & Historian, Vol. 60, No. 2 (Summer 2008), p. 158; Barry and Burt, Suppliers Vol III, p, 262.

- Stone, p. 37-38; Anthony, p. 157.

- Stone, p. 37.

- Stone, p. 38; Anthony, p. 157.

- Stone, p. 37.

- Glover, Government Contracting, p. 480 and 487.

- Ibid, p. 482.

- Leone Levi, ed., Annals of British Legislation: Being a Classified and Analysed Summary of Public Bills, Statutes, Accounts and Papers, Reports of Committees and of Commissioners, and of Sessional Papers Generally, of the Houses of Lords and Commons, vol. IV (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1859), p. 391; Peel, p. 315; Commission on Water Supply, p. 296.

- Barry and Burt, Suppliers Vol III, p. 262; Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the State of the Store and Clothing Depots at Weedon, Woolwich, and the Tower, &c. (London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1859), p. 608.

- Report of the Commissioners, p. 607 and 619-621; Glover, Government Contracting, p. 486-495; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 704 and 782.

- Report of the Commissioners, p. 92 and 620-621.

- Report of the Commissioners, p. 639; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 788; Barry and Burt, Suppliers Vol III, p. 269.

- Barry and Burt, Suppliers Vol III, p. 264-266.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 230; Glover, Government Contracting, p. 479 and 494-495; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 708.

- Third Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the Best Means of Preventing the Pollution of Rivers, Vol. II (London: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1867), p. 88; Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851: Reports by the Juries (London: William Clowes & Sons, 1852), p. 359.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 237; Jubb, p. 52.

- Malin, p. 418; Official Records of the Navies, Ser. I, Vol. 6, p. 661; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 655.

- Marlin, p. 419; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 655-656 and 724; Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 244.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 244; Marlin, p. 419; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 657.

- Glover, American Blanket Trade, p. 237; Glover, Dewsbury Mills, p. 658 and 661.

- Malin, p. 419.