By Austin Williams, 33rd Virginia Co. H

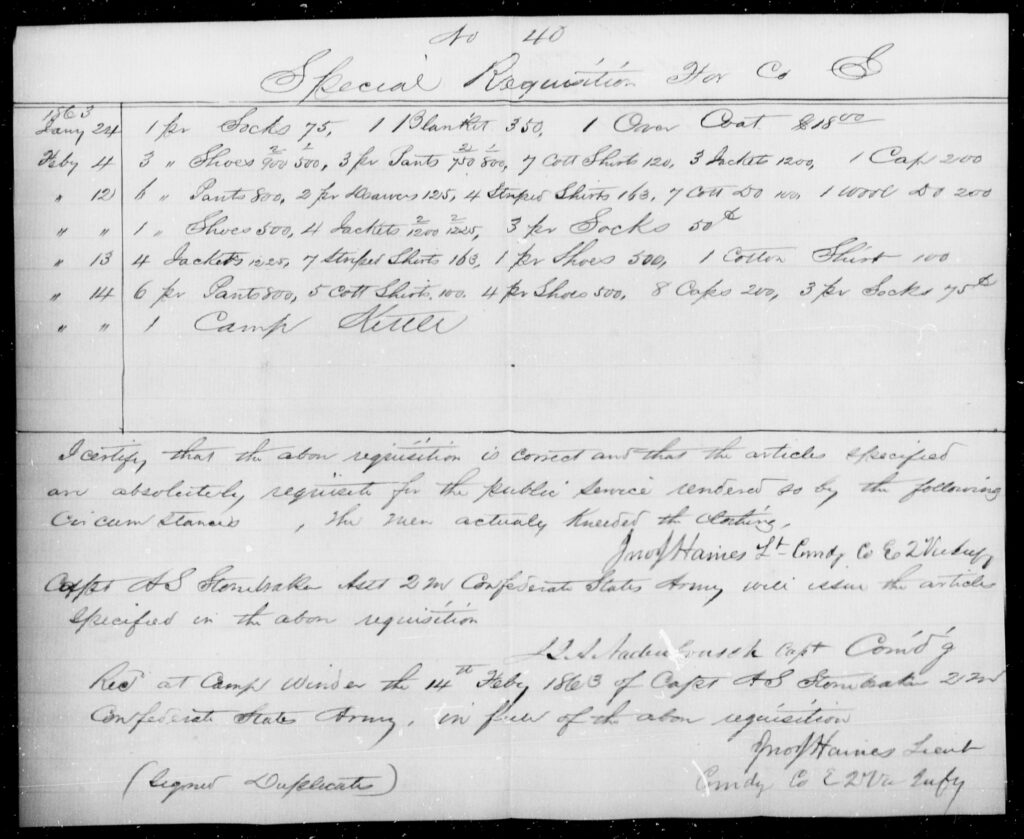

A principal challenge of studying Civil War material culture is the frustratingly limited detail available in many sources. Surviving documents only rarely mention the fabric, color, construction, or manufacturer of uniform items and never in as much detail as the modern research would like. When reviewing Confederate quartermaster requisition forms, a tremendous diversity of uniform items is concealed behind the obliquitous label “jackets,” “pants,” or “shirts.” Sometimes, however, some long-dead quartermaster gives us a tiny window into the past by deciding to take an extra second 160 years ago and add an additional descriptive word or two to a now-faded form.

Assistant Quartermaster A. S. Stonebaker of the Second Virginia Infantry took just such an extra moment in early 1863 and unknowingly provided probable insight into the use of imported British Army shirts in the Army of Northern Virginia. Encamped near Fredericksburg, the regiment received a major shipment of quartermaster stores on February 14, 1863, including at least 224 shirts. Records only survive for eight of the Second Virginia’s ten companies, so the full number was likely about 50 additional shirts. Of the shirts issued, 143 (64%) were identified by Capt. Stonebaker as being cotton shirts, while he noted nine (4%) were woolen shirts. Perhaps struck by the novelty of what he was seeing, Stonebaker wrote that the remaining 72 shirts (32%) were “striped shirts.” The single descriptor Stonebaker added allows the identification of this batch of shirts as most likely being imported blue and white striped British Army issue shirts.1

Isaac Campbell & Co.

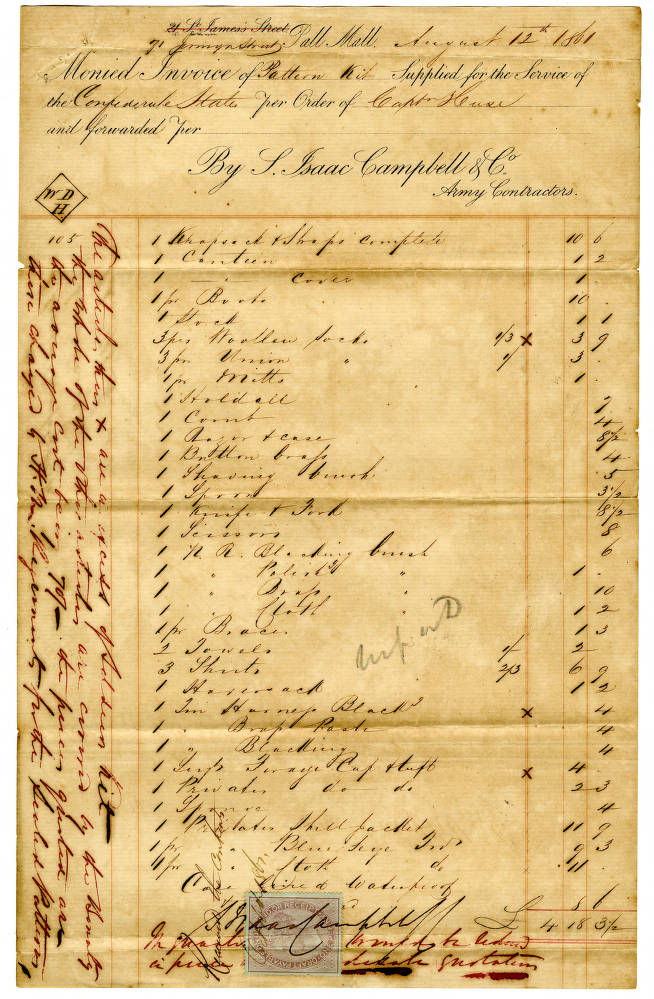

The likely path the shirts took to reach Capt. Stonebaker and the soldiers of the Second Virginia had its origins on June 27, 1861, when Confederate Capt. Caleb Huse first stepped through the doors of the London offices of S. Isaac Campbell & Co. at 71 Jermyn Street. The Ordnance Department had dispatched Huse as a purchasing agent to obtain arms, munitions, and supplies from Europe. He discovered an eager partner in Silas Isaac, who offered to leverage his firm’s network of manufacturers and subcontractors to procure whatever Huse wished to order.2

In 1861, S. Isaac Campbell & Co. was one of Great Britain’s largest commission houses. These firms operated as agents for both the buyer and seller in a transaction, extracting a percentage fee from both parties. When buyers lacked established credit or the connections to purchase directly from manufacturers, as was the case with the young Confederacy, commission houses would step in as an intermediary, finding and contracting for the desired goods from multiple parties. They would often buy in bulk directly from manufacturers and either provide or obtain credit for the buyer. S. Isaac Campbell & Co. had formerly been one of the principal British Army contractors but had lost its official contracts in 1858 amidst allegations of bribery. While supplying British volunteer units had kept the firm profitable, the company saw an eager new customer in the young Confederacy.3

During Huse’s first visit to S. Isaac Campbell & Co., he placed an initial order for 2,000 sets of accouterments. In the following weeks, he added 1,000 sabers and over 21,000 muskets to the order. Huse quickly realized that, with its extensive network of sub-contractors, S. Isaac Campbell & Co. could provide nearly anything he cared to buy. He wrote to Richmond proposing additional contracts that would make the firm almost the exclusive supplier to the Confederacy.4

The Ordnance Department responded requesting price estimates, so Huse ordered a single exemplar set of soldier’s kit from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. The kit included all the “necessities” the company had previously provided the British Army, including a knapsack, mess tin, haversack, boots, socks, shaving kit, boot black, knife and fork, towels, and other personal items. Among the items listed were three shirts, sold to Huse for 6 shillings 9 pence. The shirts and the rest of the kit arrived in Savannah on September 20, 1861 aboard the S.S. Bermuda and were forwarded to Richmond. These samples mirrored the British military practice of contractors providing a product exemplar that was then signed, sealed, and certified as being the “sealed pattern” for the contract. All future purchases could be compared against this benchmark to ensure consistent quality.5

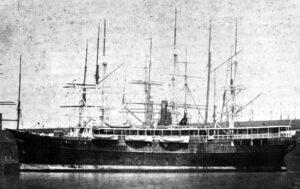

Huse’s first major shipment left Great Britain in early October aboard the S. S. Fingal, wholly owned by the Confederate government. Its cargo of gunpowder, rifled muskets, blankets, apparel, pistols, accouterments, cartridges, shells, sabers, and bayonets arrived in Savannah on November 14, 1861. Even as these imported goods began to reach the hands of Confederate soldiers, Huse and S. Isaac Campbell & Co. were hard at work preparing even larger shipments to come. Those shipments would include thousands and thousands of shirts.6

Early and Smith, Wholesale Clothiers and Slop Sellers

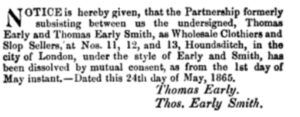

One of the manufacturers with whom S. Isaac Campbell & Co. contracted was Early and Smith of Nos. 11, 12, and 13, Houndsditch, London. The firm’s two partners initially operated independently before forming a partnership in the late 1840s. Thomas Early appeared in legal proceedings as early as 1841 as a “slop seller”, a period term for dealers in cheap ready-made clothing. Thomas Early Smith similarly appeared as early as 1845 as a clothier in Houndsditch. The two men had apparently begun doing business together by 1849, when “Early and Smith, Houndsditch” were listed as creditors in the bankruptcy proceedings of a fellow clothier and outfitter. By 1851 the pair were listed as “wholesale clothiers and copartners in trade.”7

A portion of Early and Smith’s business was supplying clothing for the British military. In addition to being listed in the 1862 London Post Office Directory as wholesale clothiers, shirtmakers, outfitters, and warehousemen, Early and Smith were also identified as army clothiers. During an 1857 investigation into the British Army’s clothing contracting, a Parliamentary committee took testimony from David Ludlow, a sub-contractor who had produced nearly 100,000 garments in 1855 and 1856 for some of the principal army clothiers, including firms like Herbert & Co. and S. Issacs Campbell & Co. that would later supply the Confederacy. Ludlow reported that during this period he had also made a “great deal” of Navy clothing for Early and Smith, including Navy coats.8

In addition to sub-contractors like Ludlow, at least some of Early and Smith’s clothing was made by prison labor. In summer 1856, a British writer toured London’s Millbank Prison. Upon visiting the prison’s manufacturing department, a prison official stated that Millbank produced clothing for almost all of England’s prisons, as well as making garments on sub-contract for British military contractors. “Yonder’s a roll of blue and white yarn, you see, ready for shirting and handkerchiefs,” pointed out the official. “Yes, sir, our female prisoners do a great deal of work for slop-shops. We work for Jackson in Leadenhall Street; Early and Smith, Houndsditch; Stephens and Clark, Paul’s Wharf, Thames Street; Favell and Bousfield, St. Mary Axe; both shirts and coats we do for them. We do a great deal of Moses’ soldiers’ coats, and Dolan’s marine coats. We take about £3,000 a year altogether from the slop-shops.”9

While military clothing was part of Early and Smith’s business, they also sold ready-made clothing to the civilian sector. A portion of their business was outfitting travelers to Australia, as advertised in an 1852 notice for “Outfits to Australia and Elsewhere” sold by the firm at wholesale prices. They were also heavily involved in the export trade, being named as parties to multiple lawsuits related to overseas shipping. In 1857, the firm became entangled in a lawsuit connected to their charter of a ship transporting goods to Quebec. The company’s assets in 1864 included consignments of still unsold goods located in Havana and Melbourne.10

At least some of the clothing sold to Huse by S. Isaac Campbell & Co. was obtained from Early and Smith. On May 24, 1862 the blockade runner S.S. Cecile arrived in Charleston with a load of British goods. Among the cargo of rifles, gunpowder, and boots were 22 trunks, 6 bales, and 39 cases all marked as being shipped by S. Isaac Campbell & Co. While the contents of the cases were not identified, 28 of the cases were marked <SIC&Co/E&S> for S. Isaac Campbell & Co./Early and Smith. Early and Smith also shipped £3,751 worth of goods to the Confederacy in August 1862 on their own private account. While the destination of this shipment was not recorded, Charleston was the principle Confederate port for British imports at this time. The merchandise was “advantageously sold” and the proceeds invested in Confederate bonds. The firm also took out £7,603 of debt for advances on a February 1864 shipment to Nassau, most likely ultimately bound for the Confederacy.11

“Under instructions from Messrs. Isaac Campbell & Co.”

In February 1863 the Ordnance Department submitted a summary of Huse’s European purchasing efforts to the Secretary of War. In addition to arms, ammunition, and accouterments for the Ordnance Department, the summary detailed purchases of £110,525 (roughly $552,625 Confederate) worth of clothing Huse had bought and shipped to the Confederacy, including 74,006 boots, 62,025 blankets, 8,675 greatcoats, 8,250 pairs of trousers, 170,724 pairs of socks, 6,703 shirts, 78,520 yards of cloth, and 17,894 yards of flannel. In total, Huse had purchased over £1,068,000 ($5,340,000) of supplies, over half of which were from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. alone.12

Although much of this material successfully arrived on blockade runners like the Cecile, at least some was intercepted by Union warships. The S.S. Stephen Hart was captured on 29 January 1862 off the coast of southern Florida with a shipment claimed wholly by S. Isaac Campbell & Co. On 3 February 1863, the S.S. Springbok was seized making for the harbor of Nassau with a cargo jointly claimed by S. Isaac Campbell & Co. and T. S. Begbie & Co. Among the ship’s papers was a letter to the agent of the cosignee operating “under instructions from Messrs. Isaac Campbell & Co” and the ship’s cargo included Confederate military buttons stamped on the back with the firm’s name and address. Federal warships captured a third ship, the S.S. Gertrude, off the Bahamas on 16 April 1863 operating under contract for Begbie & Co.13

The ships contained different portions of larger purchases of shirts and other items made by Huse. When Union authorities searched the Springbok, they found four bales marked <A>, numbered 985-987 and 989, and containing “men’s colored traveling shirts.” The Gertrude contained five bales of colored traveling shirts similarly marked <A> and numbered 998, 990-992, and 998. The Hart’s manifest included four cases of men’s shirts marked <A> and numbered 994-997. Clearly, the bales were multiple parts of a single sequentially numbered shipment from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. Likewise, the Springbok had packages marked <A> S. I., C. & Co. and numbered 1221-1440, but with a gap from 1266 through 1289, the package marked 1289 being the first of several containing shirts. Some of the missing packages were to be found on the Gertrude, which had on board packages marked <A> and numbered 1170-1214, plus a package of shirts numbered 1285.14

While the Springbok, Stephen Hart, and Gertrude all became Federal prizes, the majority of the 6,703 shirts purchased by Huse successfully reached southern ports. Some of them likely ended up in the hands of Capt. Stonebaker and the Second Virginia. Importation records into the Confederacy for Wilmington and Charleston, the principal ports supporting the Army of Northern Virginia, are incredibly fragmentary. The records for Charleston are particularly poor, with limited surviving documentation. Many of the records which do survive for Charleston do not detail cargo contents and it is unclear whether shirts may have been found in bales labeled as “army clothing,” “clothing,” “wearing apparel,” or “ready-made clothing.” For instance, the S.S. Modern Greece reached the southern shores on June 17, 1862, but records only list unquantified and unspecified “bales of clothing.” At least some of these were shirts, as Wilmington firm O.S. Bladwin soon listed for sale items from the Modern Greece including 600 French Bosom dress shirts and 1,000 merino wool shirts. Charleston was likely the primary port for many of Huse’s 1862 shipments, as Wilmington was closed from August to December by an outbreak of yellow fever. After Wilmington reopened in the winter of 1863, it quickly surpassed Charleston as the principal port, particularly for government importations.15

Importation records compiled by researcher C. L. Webster includes the following shirt imports by the Confederate government into Wilmington and Charleston during the conflict:

-

-

- 2 cases wool shirts and 1 case “shirts blue” arrived on the S.S. Ella Wartley into Charleston on 3 January 1862

- 28 cases marked <SIC&Co/E&S> arrived on the S. S. Cecile into Charleston on 24 May 1862

- 4 cases clothing marked <SIC&Co> and 4 cases “cotton clothes” marked “JRW” arrived on the S.S. Antonica into Charleston on 18 December 1862

- 5 cases “Melins shirts” marked “TAC” arrived on the S.S. Flora into Charleston on 3 January 1863

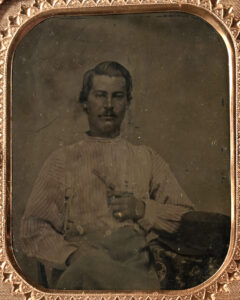

- 3 bales of “military shirts” arrived on the S.S. Flora into Wilmington on 8 Dec 1863

- 1,290 wool shirts arrived on the S. S. Lucy into Wilmington on 9 Dec 1863

- 3 bales wool shirts (1,284 total) arrived on the S. S. Dee into Wilmington on 11 December 1863

- 11 bales (1,838 total) of flannel shirts arrived on the S. S. City of Petersburg into Wilmington on 2 February 1864

- 9 bales (1,292 total) “fancy shirts” shipped from Wilmington to Richmond on 12 April 1864 from an unknown ship

- 1 bale (52 total) of “fancy shirts” shipped from Wilmington to Richmond on 13 April 1864 from an unknown ship

- 4 cases (1,698 total) of “grey army shirts” arrived on the S. S. Lucy into Wilmington on 14 May 1864

- 38 bales of flannel shirts arrived on the S.S. City of Petersburg into Wilmington on 15 May 1864

- 3 cases woolen shirts arrived on an unknown ship into Wilmington on 4 August 1864

- 2 cases grey shirts marked “N” arrived on the S.S. Siren into Charleston on 9 October 1864

- 2 cases grey shirts marked “N” arrived on the S.S. Fox into Charleston on 10 October 1864

- 6 bales socks and shirts and 2 bales shirts arrived on the S.S. Lucy into Wilmington on 25 October 1864

- 6 bales (1,300 total) of shirts arrived on the S.S. Chicora into Charleston on 7 November 1864

- 60 bales of shirts arrived on the S.S. Owl into Wilmington on 2 December 1864

- 1 case shirts (348 total) shipped from Wilmington to Richmond on 11 January 1865 from an unknown ship16

-

While Webster’s outstanding research focuses on government imports, a significant amount of material also entered the Confederacy via private enterprise. Webster estimates that, of the circa 2,700 ships that successfully ran the blockade, less than 700 carried government stores. Once these commercial ships arrived safely on southern shores, however, both the Quartermaster Department and Ordnance Department purchased large quantities of items and material via auction or direct sale. Although Wilmington was the favored destination for government importation and Wilmington-bound ships usually staged in Bermuda, commercial firms favored Charleston and often set sail from Nassau. Early and Smith’s privately financed shipment to Nassau in February 1864 discussed above may, therefore, have ultimately arrived via Charleston. Federal siege operations began around Charleston in April 1863, significantly reducing traffic into the city by summer 1863. Ships still got through, however, and there was a brief revival of commercial trade in late 1864, with the final ship arrived in Charleston a single day before the surrender of the city.17

Since commercial records are even more fragmented than the surviving records of government imports, some of our best insight into these operations comes from advertisements for the sale of imported goods. On July 14, 1862, commission merchants R.A. Pringle announced the auction of 2,000 packages of newly arrived British goods, including 936 shirts, over 7,500 military caps, and two cases of drab felt hats. In November 1862, the Richmond firm N. C. Barton & Co. announced their recent recipet of English Army overshirts and merino wool shirts and drawers. The Charleston firm Minor & Co. conducted a January 7, 1863 auction of the entire cargo of a newly arrived blockade runner. The cargo was primarily civilian goods and luxuries, but also included “Brown Linen and Worsted Army Shirts,” “40 dozen linen bosom shirts,” “Colored Bosom Shirts,” and “Gray and White Under Shirts.” Richmond papers on November 3, 1863 proclaimed the upcoming sale of goods from the blockade runner S.S. Banshee by the firm Ellett, Bell, and Fox, including 1,584 “men’s merino shirts and drawers.” Some of these shirts were undoubtedly purchased and worn by civilians, but many would have also found their way on to the backs of soldiers, either directly via purchase and issuance by the Quartermaster Department or indirectly by soldier’s families purchasing imported British shirts and then sending them to the front.18

Surviving Shirts

Of these thousands of government and commercially imported shirts, only one confirmed example of a British shirt imported into the Confederacy is known to exist. Now in the collection of The American Civil War Museum, the shirt belonged to Lt. John Selden. Born in Washington, DC, the 18-year-old Selden was studying at the University of Virginia when war began and enlisted in the Albemarle Light Artillery. He left service after a year, but reenlisted in October 1862 in the Second Company, Richmond Howitzers. He was appointed First Lieutenant and Ordnance Officer in February 1863 and was assigned to Hardaway’s Battalion Virginia Artillery. He served in this capacity until being reassigned to Cutshaw’s Battalion Virginia Artillery in late March 1865. He was paroled in Richmond on May 26, 1865.19

Selden’s garment is a white cotton shirt with blue stripes of alternating thickness, mirroring how Capt. Stonebaker described the “striped” shirts issued to the Second Virginia. Instead of the common construction style of folding the fabric at the shoulder and sewing both sides, the shirt is instead folded on one side and stitched down the other and across both shoulders. This saved material by using the full width of the bolt and eliminated the need to hem the bottom of the shirt, using the selvage instead. Along with the unusual construction, the fabric also has a weft stripe, running crosswise on the fabric, rather than the more common warp stripe that runs lengthwise. However, because the shirt is folded on the side rather than the shoulder, the stripes run vertically on the shirt.20

The shirt is constructed without pockets or placket, with the edges of the neck slit simply turned back and whip stitched. The sleeves are set with gussets at the armpits and gathered at the cuffs. The 1 ½” deep cuffs button backwards compared to modern shirt cuffs. The buttons on both cuffs and at the neck slit are all 7/8” bone three-hole buttons, while the button on the collar is a replacement porcelain Prosser patent button. An additional cloth reinforcement is behind the single neck slit button and a 1” wide reinforcement strip on each shoulder. All the seams are flat felled and sewn with a heavy unbleached cotton thread.21

Selden’s shirt is marked on the lower right in black with “WD” for “War Department” and “Early & Smith / C&M / 1859” under a broad arrow. “C&M” denotes that Early and Smith were approved Contractors and Manufactures for the British War Department, while the arrow marks the shirt as having passed inspection for use by the British military. Technically, the arrow meant the shirt remained official British Army property and should not have been sold to the Confederacy. Had the shirt been condemned or sold as surplus, a second arrow should have been added, facing the first one, to denote the shirt being taken out of service.22

While Selden’s shirt is the sole known surviving shirt of this style connected to the Confederacy, three nearly identical shirts have been discovered in Australia. 1832 regulations called for convicts deported to Australia to be issued “three striped shirts” annually. Two such shirts were recovered from the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney. Believed to date from the 1830s or early 1840s, the shirts, like Selden’s, are made from a plain weave unbleached cotton with a blue weft stripe of alternating thickness. Additional scraps of blue striped cotton have been found elsewhere at the Hyde Park site, almost certainly fragments of additional shirts which did not survive. The Hyde Park shirts share the uncommon construction of the Selden shirt, folded on the side and utilizing the selvedge instead of a bottom hem.23

A very well-preserved third shirt was discovered in the wall of the commandant’s cottage at a prison labor site in Bridgewater. Based on the date of construction on the site, it likely dates from around 1830. Possibly placed in the wall as part of a folk superstition, it appears to have never been worn. It is identical in construction and materials to the Hyde Park shirts.24

Much like the Selden shirt, these three Australian shirts are stamped as being official British military property. The Australian shirts are marked in the lower right with a broad arrow and “BO” for Board of Ordnance, the predecessor to the later War Department stamp seen on the Selden shirt. While these three surviving shirts were all issued to convicts, the style was standard British Army issue from the Napoleonic period through the later stages of the Crimean War.25

While they are nearly identical on most details, the biggest point of difference between the three Australian shirts and the Selden shirt is the collar. The Australian shirts have a higher, square collar, similar to that seen on U.S. Federal issue shirts. The fold-down collar was designed to roll over a neck stock or cravat and had an additional button on the collar at this folding point. The collar on the Selden shirt, however, is a short 1” band collar, omits the second collar button, and instead adds a single button on the neck slit that the Australian shirts lack. Interestingly, the Selden collar appears to have been a manufacturer modification, as, according to examination by researchers Craig Barry and David Burt, no fabric has been cut away. Instead, the extra fabric was simply folded down and overcast into place. The thread used was similar to that used for the rest of the shirt.26

It is unclear whether all the British Army shirts imported into the Confederacy had this lowered collar or whether Selden’s shirt was an anomaly. A possible clue may be found in a photograph in a private collection of a Confederate soldier tentatively identified as possibly a Virginia volunteer. He wears a white striped shirt that appears visibly consistent with the Selden and Australian shirts. The shirt in the photograph appears to have a lower, band-style collar like the Selden shirt, rather than the fold down collars of the Australian shirts. If this photo does show an imported British Army shirt, it suggests the collar style seen on the Selden shirt was standard on the shirts imported into the Confederacy.27

The purpose of the modification is open to debate. Late in the Crimean War, the British Army adopted a new issue shirt of grey cotton or flannel, fitted closer to the body than the square cut seen in the Selden and Australian shirts, and having an overall different construction. Flannel had become popular in the British military because it repelled moister and was warmer in the winter. These “greyback” shirts, which saw active use through the end of World War I with only minor changes, have a distinctive band collar. The Selden shirt, which is marked as having been inspected in 1859, several years after the introduction of the greyback shirt, appears to have been modified to match the greyback’s band collar.28

Why such a modification would occur is unclear. There is no reason to believe it occurred after importation to the Confederacy, as the fold down collar style was common in America at the time and was also used in both Federal and Confederate military issue shirts. Craig Barry and David Burt suggest the Selden shirt and thousands of others were penitentiary shirts rendered surplus by the reduction in transportation of convicts to Australia by the 1850s. They posit that S. Isaac Campbell & Co., or another firm, purchased the inexpensive shirts and altered them to match the regulation greyback shirt before selling them to the Confederacy.29

The Selden shirt, however, is marked 1859, years after the decline in convict transport to Australia began. Additionally, the presence of War Department and Board of Ordnance markings on the Selden and Australian shirts indicate they were British Army garments, rather than shirts made solely for use by convicts. As noted above, as of the mid-1850s Milbank Prison was making shirting material using blue and white yarn and manufactured clothing for use by both the British penal system and the British military. It is also unclear why the shirts would need to be modified prior to being sold to the Confederacy, since the modification would cut into profit margins and is unlikely to have been demanded by Huse or other buyers, since, as noted above, the existing fold down collar was comparable to both Confederate and Federal military issue shirts. Visit our partners, – leaders in fashionable footwear!

A perhaps more plausible explanation is that the modifications were initially made, not for resale to the Confederacy, but for the burgeoning British volunteer market. An 1858-1859 war scare with France had triggered the widespread formation of volunteer rifle corps across Great Britain. These home defense groups were required to provide their own uniforms and equipment and S. Isaac Campbell & Co., barred from government contracts the previous year, quickly emerged as a major supplier. Equipment for the volunteers did not need to pass the rigorous standards demanded by the Regular Army, nor exactly match the standard pattern. Although appearing to be copies of standard equipment, surviving S. Isaac Campbell & Co. accouterments made for British volunteers but purchased by Huse are visibly poorer quality than equipment manufactured by other British firms with official contracts such as Alexander Ross & Co. With the Regular Army wearing the greyback shirt by this period, perhaps S. Isaac Campbell & Co. had the older blue striped shirts modified to appeal more to volunteers eager to look more like regular Army soldiers. Regardless of the reason for the change, thousands of shirts like this and in other patterns passed through S. Isaac Campbell & Co. to Huse and onward to the Confederate Quartermaster Department and eventually Confederate soldiers.30

Scandal and Collapse

The massive amounts of shirts, clothing, blankets, and fabric Huse purchased from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. were outside his role an agent of the Ordnance Department and were obtained on his own initiative for the Quartermaster Department. In late December 1862, Maj. James Boswell Ferguson Jr. arrived in England as the Confederate Quartermaster Department’s official purchasing agent. He quickly clashed with Huse, who refused to cease purchasing Quartermaster supplies via S. Isaac Campbell & Co. In a letter to Quartermaster General Alexander Lawton, Ferguson complained “Huse has caused me more annoyance than all the others combined on this side and has defeated my plans in a great measure for keeping up the supplies of our department.”31

Even more concerning, Ferguson had grave doubts regarding S. Isaac Campbell & Co. Unlike Huse, whose pre-war career had been as a soldier and educator, Ferguson had over twenty years of business experience. He was also intimately knowledgeable with the textile industry, having previously operated his own import and export firm, Ferguson JB, Jr. Bros & Co. Clothes, Cassimeres and Vestings. Reviewing Huse’s invoices, Ferguson believed the prices charged by S. Isaac Campbell & Co. were exorbitant. He also examined some of the fabric purchased by Huse from the firm and believed it worth only roughly half the price. On top of all these, Huse admitted to Ferguson he had personally accepted a commission from S. Isaac Campbell & Co.32

On May 26, 1863, Confederate financial agent Colin J. McRae was instructed to investigate Ferguson’s allegations of bribery and price gouging. He began an audit of Huse’s accounts in August and then began to look into Ferguson’s claims in October. As part of the investigation, McRae contracted with a London accounting firm to conduct a complete audit of S. Isaac Campbell & Co. The review took months, but finally in summery 1864 McRae determined that S. Isaac Campbell & Co. had been keeping two different sets of books. They had been systematically overcharging Huse by as much as 20%, well above the agreed upon commission. After the firm refused to pay back the money, the matter was submitted for legal arbitration, which continued through the end of the year.33

McRae’s final report in October 1864 acknowledged that Huse had been wrong to rely on a single commission house but cleared him of personal misconduct. “It was not our intention…” McRae wrote, “to clear him from blame, but to relieve him from any charge of collusion…. We wished to keep from speaking too severely of his mistakes because of the difficulties of his position, but not to endorse or overlook them.” Flawed though it may have been, Huse’s work with S. Isaac Campbell & Co. had brought massive amounts of critically needed supplies into the South. Confederate business with the firm had slowed significantly in 1863 following Ferguson’s arrival and now stopped almost altogether.34

Around the same time that McRae was bringing legal action against S. Isaac Campbell & Co., Early and Smith faced financial disaster. Much of the firm’s financing had come from the Leeds Banking Company. The bank failed on September 16 following “a long course of reckless extravagance” and “reckless management” by the bank’s director Edward Greenland. The bank was over £500,000 in debt, ruining the majority of the bank’s shareholders. Greenland was tried and convicted of perjury for falsifying official returns.35

The collapse of Leeds Banking Company caused the cascading failure of multiple firms backed by the bank. On September 30, Early and Smith were unable to make payments on their debt and entered bankruptcy proceedings. The firm was £81,369 in debt and had only £28,079 in assets. Among their liabilities were advances for their August 1862 shipment to the Confederacy and their February 1864 shipment to Nassau. They had £9,260 worth of assembled or partially assembled clothing still on hand. The company’s stock was sold at a heavy discount to cover the firm’s debts. On May 1, 1865, Early and Smith mutually agreed to formally dissolve their partnership. A year later, Smith remained in business as a clothier in the firm’s former offices at No. 11 Houndsditch. His business continued through at least 1868, when he gave his occupation as clothier during testimony in the prosecution of one of his employees for embezzlement.36

No Article More Serviceable to the Army

With the decline of Huse, S. Isaac Campbell & Co., and Early and Smith, Ferguson took over the preeminent role in procuring Quartermaster supplies from England. Huse’s inexperience had made the use of an intermediary like S. Isaac Campbell & Co. a necessary expedient. Instead of Huse’s cozy relationship with the London-based commission houses, Ferguson established his base of operations in Manchester, the heart of England’s cloth industry. This and his pre-war textile experience allowed him to deal more directly with manufacturers rather than middlemen. He appears to have focused on importing cloth and other raw materials rather than finished goods. Among his first orders was for 1,000,000 yards of wool cloth. Purchasing shirts does not appear to have been a major focus for him, particularly since they could be made from cotton, one of the few resources the Confederacy still had in relative abundance.37

What shirt purchases he did make, however, appear to have been largely made from wool flannel. On September 23, 1864, Lawton penned a letter to Ferguson with guidance on his procurement activities. “There is no article more serviceable to the Army for fall and winter wear,” he wrote, “than the flannel or worsted shirts, or the material for their manufacture.”38

Wool flannel shirts, often grey in color, had been arriving from England since at least January 1862, when two cases of wool shirts arrive in Charleston on the S.S. Ella Wartley. It is possible that some of the nine woolen shirts issued by Captain Stonebaker to the Second Virginia in early 1863 along with the “striped shirts” were imported from England. Between December 1863 and February 1864, 4,412 wool shirts arrived in Wilmington. Likely over 7,000 wool shirts arrived in May 1864 alone, with 1,698 “grey Army shirts” listed on the manifest of the S.S. Lucy and another 38 bales of flannels shirts on the S.S. City of Petersburg.39Despite the scandalous result of McRae’s audit several months before, Ferguson purchased 14 bales of grey wool shirts from S. Isaac Campbell & Co. on December 19, 1864, representing the last major Confederate purchase from the firm. It is unknown whether these roughly 2,000-3,000 shirts were ever successfully delivered.40

Little is known about the style and construction of these flannel shirts, as there are no known surviving examples of an identified imported British wool shirt. The May 1864 manifest of the S.S. Lucy specify that its cargo included “grey army shirts,” while the S.S. Siren and S.S. Fox delivered several cases of “grey shirts” into Charleston in October 1864. These suggest that at least some woolen shirts were modeled on the British Army’s standard issue flannel “greyback” shirt.41

Researchers Barry and Burt assess no “greyback” shirts were imported by the Confederacy, but at the very least, commercial firms offered the Confederacy shirts copied from the British Army issue garment. In December 1863, James Tait, representing the Limerick firm Peter Tait & Co., wrote to the Confederate Secretary of War with an offer to ship “50,000 Strong Grey Flannel shirts ready for sewing” within the first three months of 1864. The shirts would be cut according to the size rolls used by the British Army to cloth men between 5’6” and 6’ tall. Tait assured Seddon that the shirts would be “subjected to the same rigid inspections” and would be the same quality as those in use by the British military. Although Lawton wrote to Tait confirming the order a few days later, it does not appear to have ever been filled.42

While it lacks any markings that would confirm British origin, a blue wool flannel shirt in the collection of the North Carolina Museum of History may represent a style imported from England or at least may have been made from British cloth. The shirt belonged to Pvt. John MacRae, a member of Company B of the 13th Battalion North Carolina light Artillery. MacRae reportedly wore the shirt during the Battle of Bentonville, and it survives in relatively good condition, strongly suggesting it was issued late in the conflict. The Museum notes that it may have been made of imported British cloth. Lending further credence to a potential British connection, the museum collection also includes a S. Isaac Campbell & Co. knapsack carried by MacRae.43

North Carolina conducted its own procurement and importation separate from that of the Confederate Quartermaster Department, and it is likely this state-run operation that supplied MacRae. Governor Zebulon Vance dispatched a special commissioner, John White, to England to sell cotton bonds and obtain supplies for the state. During the year that White spent in England from December 1862 through December 1863, he purchased significant amounts of material, mostly via Alexander Collie & Co. These included 9,792 gray flannel shirts and 1,956 “Angola” wool shirts, as well as 111,755 yards of grey flannel cloth, all of which were scheduled to be shipped prior to January 1864. As of September 30, 1864, the North Carolina Quartermaster Department had issued 6,000 flannel shirts obtained via foreign import. Another 3,960 flannel shirts remained in state warehouses at the time, and it is possible one of these shirts made it onto the back of Pvt. MacRae.44

MacRae’s shirt was made of plain weave blue and unbleached wool flannel. It has a short band collar, similar to collar seen on the “greyback” and Selden shirts and further supporting a possible British origin. In addition to a button on the collar, the shirt has three buttons on the placket, which is 2 ¼” wide and 12” long. All the buttons are ½” in diameter and, while three are likely replacements, a four-hole bone button on the placket may be original. The shirt has a 1 3/8” reinforcement at the shoulder line and a patch style pocket on the left breast. The pocket is set at an angle and has a rounded bottom. The one-piece sleeves are set without gathering and have square underarm gussets. The sleeve is pleated at the cuff, with a small gusset. The cuffs are 3 ¼” long and have a single button each. The shirt is handsewn using French seams.45

Wool shirts like MacRae’s, however, were never as widely issued to Confederate soldiers as cotton shirts were. Wool shirts represented only four percent of the shipment of shirts received by the Second Virginia in early 1863. In the final quarter of 1863, the Fifth Virginia Infantry was issued 312 cotton shirts, but only 100 wool shirts. In the final two quarters of 1864 and early weeks of 1865, the Confederate Quartermaster Department issued 157,727 cotton shirts and 21,063 flannel shirts to the Army of Northern Virginia. This means that just over 13% of the shirts issued during this period were wool.46

Conclusion

British import shirts likely saw only limited service in the Army of Northern Virginia. They would always be outnumbered by simple cotton shirts sewn from domestic southern cotton. Yet British imports constituted an important and mostly overlooked portion of the garments issued to Confederate soldiers throughout the war. While most of those over 150,000 cotton shirts issued to the Army of Northern Virginia late in the war were almost certainly domestically produced by the Richmond Clothing Bureau, that number probably also includes the British Army import shirt worn by Lt. Seddon, as its relatively good condition suggests he received it during this later period. Records are too fragmentary to state for certain the number of British shirts imported by the Confederacy. A rough estimate based on the government import records compiled by Webster includes the import of at least 40,000 British shirts, but given the fragmentary nature of surviving records, this likely represents a mere fraction of the actual number that ran the blockade.47

Even harder to quantify is how many shirts, particularly wool flannel shirts, were cut from imported British fabric. As the Confederacy’s domestic supplies of wool were exhausted, many of the late war wool shirt issues, like the 21,000 issued to the Army of Northern Virginia or the shirt worn by Pvt. MacRae, were probably made from imported British cloth or imported already manufactured in England. State quartermaster departments, private importation of English shirts for both the military and civilian sectors further challenge our ability to quantify the number of British shirts in the ranks of the Army of Northern Virginia.48

British shirts continued to flow into the Confederacy nearly to the end. On December 2, 1864, the S.S. Owl tied up in Wilmington with possibly the largest shipment of shirts in her cargo hole, a full 60 bales. If these bales were average sized, that could have been 9,000 shirts.49 Perhaps among these shirts was a white and blue striped British Army shirt, sewn by a British inmate five years before on commission for the firm of Early and Smith. The company, bankrupt and with just months before its final dissolution, might have sold the shirt in the fall of 1864 to another English firm as part of the liquidation of its few remaining assets. Perhaps Ferguson purchased the shirt and shipped it to Bermuda, where it was transferred to the Owl and sprinted past Federal ships into Wilmington. The bales of clothes would have then made their way north over the South’s deteriorating rail system and eventually into the besieged city of Petersburg. There, it found its way onto the back of a young Virginia artillery lieutenant. Unlike the thousands and thousands of such shirts, this one somehow survived. From surviving garments like those belonging to Lt. Seddon and Pvt. MacRae, photos like the unknown Confederate soldier in likely a British Army shirt, or rare detail in documents like Capt. Stonebaker’s requisition forms, we slowly expand our understanding of Civil War material culture.50

Footnotes

- Complied Service Records of Charles H Stewart – Second Infantry, Henry F Barnhart – Second Infantry, Samuel T Grubbs – Second Infantry, Edmond Lee Hoffman – Second Infantry, John J Haines – Second Infantry, William Strother Barton – Second Infantry, William C Sheerer – Second Infantry, Charles A Marshall – Second Infantry, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations From the State of Virginia, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C. The companies with missing records are Companies A and H.

- Craig L. Barry and David C. Burt, Suppliers to the Confederacy Vol. II: S Isaac Campbell & Co., London, Peter Tait & Co., Limerick (Fairfield, OH: The Stainless Banner Publications, 2014), p. 40.

- Ibid., p. 3 and 38.

- Ibid., p. 40.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. II, 40-41; C. L. Webster, Entrepôt: Government Imports into the Confederate States (Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press, 2010), p. 48.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. II, p. 47-48; Webster, p. 50-51.

- Perry’s Bankrupt Gazette, August 21, 1841; Trade Protection Record, October 13, 1849; Henry Hodgson, Colley Scotland, and Francis Russell, Reports of Cases Connected with the Duties and Office of Magistrates, Vol. XX (London: Edward Bret Ince., 1851), p. 32.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. II, p. 192-195; House of Commons, Reports from Committees: Contracts for Public Departments, Session 30 April-26 August 1857, Vol. XIII (London: House of Commons, 1857), p. 315.

- Henry Mayhew and John Binny, The Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life (London: Griffin, Bohn and Co., 1862), p. 253-254.

- The British Banner, June 30, 1852; “Reports of Cases Decided in all the Courts of Equity and Common Law in Ireland,” The Irish Jurist (1848-1867) 11 (1858), p. 22-23; D. Morier Evans (ed.), The Banking Almanac, Directory, Year Book, and Diary for 1866 (London: Richard Groomsbridge and Sons, 1866), p. 60.

- Webster, p. 133 and 150; Evans, p. 59.

- Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 4, Vol. 2, (Washington: War Records Office, 1897), p 382-383; Craig L. Barry and David C. Burt, Suppliers to the Confederacy: British Imported Arms and Accouterments (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2012), p. 41.

- The Springbok (U.S. Supreme Court, 1866).

- Ibid.

- Webster, p. 77, 103, 145-146, and 148; Weekly Standard (Raleigh), July 16, 1862; Wilmington Journal, August 7, 1862.

- Webster, 103-128 and 149-153.

- Ibid, p. 45, 133, 144, and 145-146, and 148.

- Webster, p. 41; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 7, 1862; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), January 2, 1863; The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), November 3, 1863.

- Complied Service Records of John Selden – First Artillery (Second Virginia Artillery), Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations From the State of Virginia, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Leslie Jensen, “British Army Shirt with a Confederate History,” Military Collector and Historian (1975), p. 178; Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 67.

- Jensen, p. 178; Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 68-69.

- “Object Record: Shirt,” American Civil War Museum, 2020, https://acwm.pastperfectonline.com/Webobject/E90D85DB-670E-4200-96EA-215164510420; Barry and Burt, Vol. I, p. 31, Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 74.

- Fiona Starr, “An Archaeology of Improvisation: Convict Artefacts from Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, 1819–1848,” Australasian Historical Archaeology 33 (2015), p. 42-43; “Hyde Park Barracks Convict Shirt,” Australian Dress Register, https://australiandressregister.org/garment/259/.

- Kristi Graham, “Object Biography: Bridgewater Convict-Era Shirt,” National Museum of Australia, https://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/9953/Bridgewater_convict_era_shirt.pdf.

- Starr, p. 42; Hyde Park Convict Shirt; Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 67.

- Craig L. Barry and David C. Burt, Suppliers to the Confederacy III: British and European Imported Quartermaster Goods, Artillery and Other Ordnance (St. Petersburg, FL: BookLocker.com, 2017), p. 70-71.

- “Confederate Volunteer with Slouch Hat and Import English Army Shirt,” The Horse Soldier, https://www.horsesoldier.com/products/photography/hard-images/tintypes/38074.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 67-68, 70-71, and 76.

- Richard M. Milstead, “Richmond Depot Clothing – Volume II – Characteristics and Anomalies: More Jackets, Pants, Drawers, and Shirts,” The Liberty Rifles, 2021,https://www.libertyrifles.org/research/uniforms-equipment/richmond-clothing; Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 72.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. I, p. 23-25.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. II, p. 67.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. II, p. 68-69.

- Ibid., p. 78, 82, 84, and 87-92.

- Ibid., p. 92.

- House of Commons, “Case of Edward Greenland, Debated on Monday 5 August 1867,” UK Parliament, https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1867-08-05/debates/f6151465-4544-45ac-addf-8894f886361c/CaseOfEdwardGreenland.

- The Money Market Review, February 25, 1865; Express (London), October 1, 1864; Evans, p. 59-60; London Gazette, May 26, 1865; “Old Bailey Proceedings, 7th May 1866,” Old Bailey Proceedings Online, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/print.jsp?div=t18660507; “Old Bailey Proceedings, 27th January 1868,” The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?name=18680127.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 67 and 76.

- Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, (Washington: War Records Office, 1897), p. 684.

- The number of shirts in each bale varied widely, from as few as 52 to as many as 428. The author uses here a conservative estimate of 150 shirts per bale for the shipment carried by the City of Petersburg.

- Webster, p. 110-112, 117, and 149; Complied Service Records of Charles H Stewart, Henry F Barnhart, Samuel T Grubbs, Edmond Lee Hoffman, John J Haines, William Strother Barton, William C Sheerer, and Charles A Marshall; Barry and Burt, Vol. II, p. 92.

- Webster, p. 153 and 117.

- Barry and Burt, Vol. III, p. 68; Barry and Burt, Vol. II, p. 182-184.

- “Military Uniform; Shirt,” North Carolina Museum of History, https://collections.ncdcr.gov/mDetail.aspx?rID=1917.42.1&db=objects&dir=MOH%20MUSEUMOFHISTORY&osearch=MacRae&list=res&rname=&rimage=&page=1.

- Walter Clark, Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, Vol. 5 (Goldsboro, NC: Nash Brothers, 1901), p. 453 and 457-458; Webster, p. 124.

- North Carolina Museum of History.

- Complied Service Records of Charles H Stewart, Henry F Barnhart, Samuel T Grubbs, Edmond Lee Hoffman, John J Haines, William Strother Barton, William C Sheerer, and Charles A Marshall; Complied Service Records of John D Brooks – Fifth Infantry, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations From the State of Virginia, Record Group 109; National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Official Records, Ser. 4, Vol. 3, p. 1041.

- Jensen, p. 176; Webster, p. 103-128 and 149-153.

- For an in-depth analysis of the Confederate textile industry, see Harold S. Wilson, Confederate Industry: Manufacturers and Quartermasters in the Civil War (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2005).

- As noted above, an average bale size appears to have been circa 150 shirts. The smallest recorded bale of shirts was 52, which put a low-end estimate of the Owl’s cargo at 3,120 shirts. The largest recorded bale was 428 shirts, and, if the Owl shipment had bales this size, the shipment could have been over 25,000 garments.

- Webster, p. 127.

Excellent article! There are some more surviving/identified shirts of interest that may be British imports, or constructed domestically from imported fabric. Two of them are pictured on pages 76 and 77 of “Don Troiani’s Civil War Soldiers” however the captions are swapped. Unfortunately the Geo. W. Wilson shirt is not yet included on the Smithsonian’s website but the Nagle shirt is. In addition to those the catalog also has this one that conforms to the overall style of the British “gray back” issue shirt.

https://www.si.edu/object/shirt:nmah_398517

https://www.si.edu/object/shirt:nmah_448850