By Austin Williams, 5th VA Co. A

Curious ladies and young boys lined the streets of Richmond on the morning of July 15, 1862, eager to catch a glimpse of Stonewall Jackson’s veterans as their columns marched through the city. Over the preceding months, the Richmond newspapers had breathlessly described the exploits of these men in the Shenandoah Valley and their timely arrival to help drive back the Union army which had threatened the city with capture only weeks before. “Imagin[ing] them to be more than common mortals,” wrote an officer in the Stonewall Brigade, “I think the boys and ladies are somewhat disappointed when they find us looking so much like the rest of humanity.”1

The Stonewall Brigade, along with the rest of Jackson’s command, had spent the previous two weeks warily monitoring the Union Army of the Potomac, which had been driven back to the James River during the recent Seven Days Battles. Marching from its camp near Mechanicsville on the morning of July 15, the brigade wound its way through Richmond’s streets, bound for trains headed north. Although the threat to Richmond from the Army of the Potomac had been contained, news had recently come south of the formation of a new Union army under Major General John Pope. The freshly christened Army of Virginia had been formed by uniting several scattered Union commands, including several Jackson had so recently outmaneuvered in the Shenandoah Valley. Advancing south, this Pope’s army presented a fresh threat to Richmond that needed to be dealt with.2

The Stonewall Brigade waited nearly two hours at the Richmond train station as other troops clambered aboard the cars. Seventeen freight trains of around fifteen cars each would work around the clock for the next two days to transport Jackson’s command north to counter Pope. Having been recently paid, the waiting Virginians flocked to the shops and restaurants surrounding the depot. In the Twenty-Seventh Virginia, Lieutenant Alfred M. Edgar eagerly purchased four apple pies. The young man’s stomach, however, could accommodate only three of the pies, forcing him to share the fourth with another member of the unit.3

The trains that day took the Stonewall Brigade to just north of Hanover Junction, where Union cavalry had burnt the bridge over the South Anna River. The following day, they clambered back onto the cars and rode as far as Louisa Court House, where they remained until the morning of July 19. That day’s march took them to Gordonsville and just beyond, where they remained for a couple days. On July 21, the soldiers of the brigade broke their bivouac and directed their line of march north along the road leading towards Madison Court House. Ascending over the low Southwest Mountains, about three miles from Gordonsville the column took a road off to the left. Halting after covering a final mile, the Virginia infantrymen established camp in “a fine piece of woods, on high, dry ground.” The camp was quickly named Camp Magruder, as the woods were jointly owned by Oliver H. P. Terrell and Major Allan B. Magruder, a brother of the Confederate general.4

Everything Has a Happy, Quiet Appearance

Veterans of the Stonewall Brigade would fondly remember the next few weeks. Two days after arriving at Camp Magruder, staff officer Major Elisha F. Paxton wrote, “Everything here seems so quiet. The troops are drilling, and there is every indication that the troops will rest here for some time. Considering the severe hardships through which they have passed since the war began, it is very much needed. Everything has a happy, quiet appearance, such as I have not seen in the army since we were in camp this time last year after the battle of Manassas.” The men conducted only light drilling and junior officers, such as Captain Michael Shuler of the Thirty-Third Virginia, busied themselves updating long neglected company muster and pay rolls.5

The men’s rest was interrupted on the morning of July 24 by reports of an enemy advance on Orange Court House. Ordered to immediately cook two days rations, the Stonewall Brigade marched from Camp Magruder at about 9 AM and withdrew to a position near Gordonsville. They spent the day lying in line of battle in a stand of woods until word arrived that the enemy probe had been repelled. By evening, the brigade had returned to Camp Magruder.6

Reveille sounded for the Stonewall Brigade at 2:30 AM on July 29 and by sunrise they again left Camp Magruder behind. Captain Shuler took a moment to note in his diary, “Nothing known, as usual, as to where we were going.” The brigade marched back to Gordonsville and then south along the Green Spring Road. Having covered about eleven miles, the brigade halted just past a tiny hamlet called Mechanicsville. There at “the edge of the rich ‘Green Spring’ oasis” near the Three Notch Road and around nineteen miles east of Charlottesville, the unit established a new camp.7

Another period of rest followed for the brigade, with the men enjoying the beautiful surroundings and mostly fair, if warm, weather. Soon after arriving in the Green Springs area, Captain Shuler wrote, “We have been drilling and setting up camp as though we were going into Regular Encampment.” Rations included flour, beef, sugar, salt, rice, and occasionally molasses. Private Thomas Smiley of the Fifth Virginia told his aunt, “We have had very good living for a few days… apples are plenty and we make a great many pies and dumplings which though not quite so good as home manufacture are a very good substitute.”8

All was not entirely idyllic, however. The men dubbed their encampment Camp Garnett, after their former commander Brigadier General Richard B. Garnett, whom Jackson had court-martialed earlier that year. The man who replaced Garnett as commander of the Stonewall Brigade, Brigadier General Charles S. Winder, had a well-earned reputation as a strict disciplinarian. By early August, tensions began to boil over. Winder placed the commander of the Thirty-Third Virginia, Colonel John F. Neff, under arrest over a minor protocol disagreement. Then, determined to limit straggling in the unit, Winder ordered anyone absent at evening roll call to spend the following day bucked and gagged, a punishment in which a man’s hands would be bound at the wrists, his arms slipped over his knees, and a stick placed between his legs to hold him in the uncomfortable position. Winder’s officers reportedly protested that the punishment was too harsh, but the general would not relent.9

The day after Winder’s order, Private John Casler of the Thirty-Third Virginia and about thirty other men of the Stonewall Brigade made their way into camp after the evening roll. Accordingly, Winder ordered they spend the following day bound and gagged under guard. Casler claimed half of the punished men promptly deserted the following night. Some of the officers complained to Jackson, who promptly informed Winder that he did not want to hear of any further bucking in his former brigade. Years after the war, Casler would write that Winder was “a good general and a brave man… but was very severe, and very tyrannical.” Casler claimed that after the bucking incident, hardly a day would pass without someone in the Stonewall Brigade darkly muttering that Winder’s next battle would be his last. Casler, however, is the only source to record such claims and, as Casler claimed to be among those punished by Winder, there must be some question to the accuracy of his mutinous allegations.10

The Hottest Day I Ever Experienced

On August 4, reveille rang through camp at 2:30 AM. The men prepared to march at first light, but soon the orders were countermanded, and the rest of the day passed uninterrupted. Later that day, however, the Twenty-Seventh Virginia received a notable delivery from the Quartermaster Department. Their commander acknowledged receipt of a new battle flag and staff. Since the previous fall, the Twenty-Seventh and its sister regiments had fought under the Virginia state flag. Now they would march for the first time under the blue Saint Andrews cross against a red background adorned with white stars. Battle flags produced in Richmond during this period were of wool bunting, trimmed on three sides with orange bunting. No records have yet been found for similar issues of flags to the other regiments of the brigade in this period, although a surviving flag believed to have belonged to the Fifth Virginia bears the orange trim indicative of flags issued around this time. While we cannot be certain whether the other regiments also received new flags in early August, it is possible the Stonewall Brigade would march into the coming battle carrying pristine new banners.11

The following day’s quiet was shattered in mid-afternoon by the unexpected beating of drums sounding the long roll. The men quickly broke camp and were on the move by 3 PM. They marched north through Gordonsville under a blazingly hot sun. Private Smiley recorded that “it is so warm now that it is very laborious marching.” Making their way along familiar roads, the Stonewall Brigade soon found itself back in the pleasant shade of Camp Magruder.12

After nearly three weeks of monitoring Pope’s movements, Jackson had learned that a portion of Pope’s army was isolated in an advanced position near Culpeper Court House. He resolved to attack and crush this detachment before Pope could concentrate his forces. On August 7, Jackson issued orders for his command to advance from the Gordonsville area. At around noon, the men of the Stonewall Brigade received orders to cook two days rations and were issued eight days’ worth of hard tack. They spent the afternoon poised to move, until orders finally arrived at about 4 PM. With the Stonewall Brigade leading the column, their division marched northeast towards Orange Court House. They halted after covering about six miles, laying down to sleep that night in a wheatfield around a mile and a half from Orange.13

They had marched, however, without their general. For the past few days, Winder had been stricken with a high fever and the brigade surgeon had implored him not to ride with the unit. Winder, however, feared leaving his men without a commander if there was to be battle and sent one of his staff officers, Lieutenant McHenry Howard, to question Jackson as to the army’s plans. Howard found Jackson on his knees packing an old-fashioned carpet bag. The young officer nervously asked Winder’s question, expecting a repute from the famously secretive Jackson. Instead, Jackson responded with a slight smile, “Say to General Winder that I am truly sorry he is sick – that there will be a battle, but not tomorrow, and I hope he will be up.” Jackson had Howard relay to Winder that he should stay behind to rest and could rejoin his command the following day near Madison Mills along the Rapidan River.14

The Stonewall Brigade marched through Orange Court House on August 8, sweating under a remorseless sun. Temperatures soared as high as 96 degrees. In the Thirty-Third Virginia, several men dropped from heat stroke. The soldiers were further annoyed by Confederate cavalry galloping by their column, the infantry complaining of the “impertinence” of their mounted comrades. That cavalry, however, was rushing to the front to push back Union troopers patrolling the north bank of the Rapidan River. Their way now clear, the Stonewall Brigade and the rest of Jackson’s command splashed across the Rapidan and bivouacked in some woods about a mile past the river.15

Soon after they halted, Winder rode into camp and immediately laid down to rest, without formally notifying anyone of his arrival. The ill general’s sleep that night was interrupted by the sound of scattered firing to the west as Union cavalry took advantage of a nearly full moon to launch a probe along the road from Madison Court House. The following morning, one of Jackson’s staff officers rode up to Winder’s tent. Believing a battle to be imminent, relayed the staff officer, Jackson instructed Winder to turn over command of his brigade to his senior subordinate and head to the rear. Winder promptly refused, proclaiming that he would not abandon his post on the eve of battle.16

Unsure what to do in the face of Winder’s refusal, the staff officer took Winder to speak with Jackson. Jackson repeated his order and Winder again refused. “Well, General, I will stick to my order as to the brigade,” Jackson replied. “If you will not go to the rear, you will take command of the division.” Ever since Jackson had risen to higher command, his own division had been without a permanent commander. With its most senior officer, Brigadier General Alexander R. Lawton, detailed with his brigade to guard the wagon train, Winder was the division’s ranking officer. The two men shook hands. Jackson rode towards the front and Winder wheeled his horse to take command of his division. It would be the last time the two men would see each other.17

With Winder now leading the division, command of the Stonewall Brigade fell to Colonel Charles A. Ronald of the Fourth Virginia. His regiment would be led into the coming battle by Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. Gardner. Lieutenant Colonel Lawson Botts was in command of the Second Virginia and Major Hazel Williams led the Fifth Virginia. With Colonel Neff still technically under arrest, Lieutenant Colonel Edwin G. Lee was the ranking officer in the Thirty-Third Virginia. The Twenty-Seventh Virginia, always the smallest regiment in the brigade, was led by a junior officer, Captain Charles L. Haynes.18

No solid evidence exists for the strength of the Stonewall Brigade on August 9. Just three months before, they had numbered nearly thirty-seven hundred men. Since then, however, their ranks had been severely thinned by battle, disease, and desertion. In July, Colonel Neff had complained that around three hundred and fifty men from his regiment were absent without leave. The only regiments which recorded their strength for August 9 were the Twenty-Seventh Virginia, which went into battle with less than one hundred and thirty men, the Thirty-Third Virginia, which marched out of camp with one hundred and sixty men in the ranks, and the the very large Fifth Virginia, which boasted five hundred and nineteen muskets. Depending on whether the other two regiments had deteriorated at roughly the same rate as the Twenty-Seventh and Thirty-Third or whether their attrition was closer to the Fifth Virginia, the Stonewall Brigade was possible somewhere between twelve hundred or seventeen hundred men as they stepped off from Madison Mills on the morning of Saturday, August 9, 1862.19

The new dawn brought no respite from the previous day’s scorching heat. Lieutenant Edgar recalled it as “the hottest day I ever experienced,” while a Federal soldier marching towards the Stonewall Brigade stated that “the air was as hot as a bake oven.” In the Thirty-Third Virginia, as least ten men fell out of the ranks due to the heat, further reducing the already small regiment’s strength. The sweating Virginians choked on the oppressive dust kicked up by the division marching before them. These units would occasionally halt for no reason readily apparent to the suffering Stonewall Brigade, causing innumerable delays as the sun bore down on the paused column of men. Captain Samuel J. C. Moore of the Second Virginia described the day’s march as “slowly feeling our way for seven or eight miles.” North of the Rapidan, the Culpeper Road upon which the men toiled gently rises and falls in a series of low ridges. As they crested each of those ridges, the men of the Stonewall Brigade could see, growing ever closer off to their right, a dark, imposing height the locals called Slaughter Mountain.20

My Poor, Poor Wife

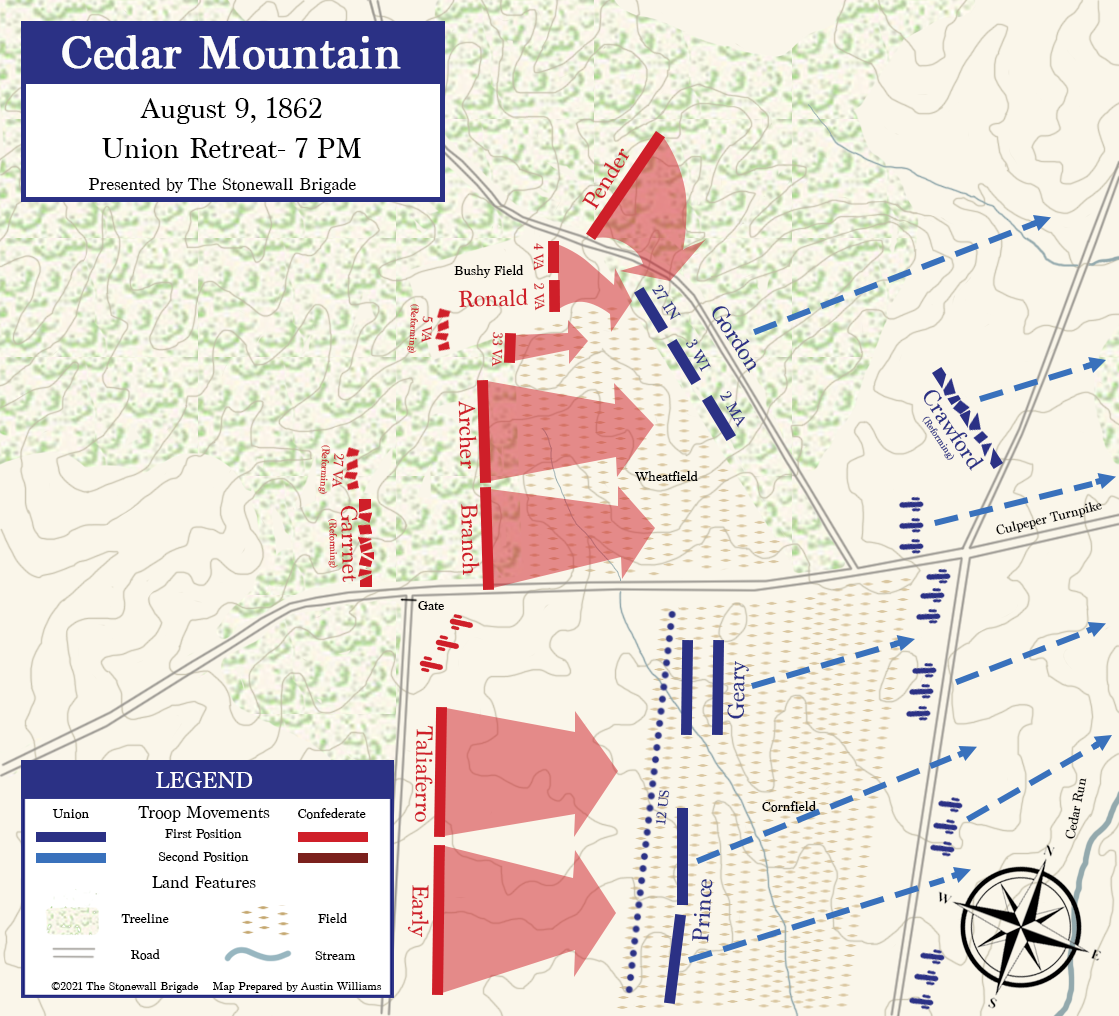

As the advance guard of Jackson’s command neared Slaughter Mountain, they spotted Union cavalry in the fields to the right of the Culpeper Road. Jackson ordered the first division in his column, under Major General Richard S. Ewell, to drive back the Union troopers. Brigadier General Jubal A. Early deployed his brigade in the open fields to the right of the road and began to press forward. Cresting a small ridge, they saw before them open and broken country bisected by the Culpeper Road. On their right off to the east rose the mass of Slaughter Mountain, which in the years after the battle would come to be more commonly known as Cedar Mountain. Directly to their front was a large cornfield, through which the Union cavalry was retreating. To the west of the Culpeper Road, a stand of woods advanced some distance before it met a freshly-cut wheatfield. North of the wheatfield rose a hill covered in dense timber. Spotting Union batteries deploying on the far side of the cornfield, Early withdrew his brigade to just behind the crest of the slight ridge and had his artillery begin a “rapid and well-directed fire” on the Union guns.21

The Union battle lines deploying opposite Jackson were from the Army of Virginia’s Second Corps, commanded by Major General Nathaniel Banks. Pope, realizing that Jackson was moving against Culpeper, had on August 8 begun to concentrate his forces and directed Bank’s corps, then at Culpeper, to advance and delay Jackson’s advance. Nearly as soon as the last echo of gunfire from the Battle of Cedar Mountain fell away, the first shots would be fired of a battle of words between Pope and Banks as to what exactly Pope’s intentions for Banks had been and whether Banks had sought battle against Pope’s wishes. Regardless of what Pope had intended, Bank’s circa 9,000 men in two divisions would soon be facing off against Jackson’s roughly 22,500 men.22

Banks had initially deployed a brigade of infantry under Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford and Battery E of the Pennsylvania Light Artillery, commanded by Captain Joseph M. Knapp, to support the cavalry. When Early’s men drove back the troopers just a little after noon, it was a few shots from Knapp’s four guns which caused Early to pause and reposition his line. By 1:30 PM, additional Union soldiers had streamed onto the field. To the east of the Culpeper Road, replacing the cavalry and Crawford’s Brigade, Banks posted the three brigades of his Second Division under the command of Brigadier General Christopher C. Augur. He then shifted Crawford’s Brigade, part of his First Division commanded by Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams, to the west of the road. The other brigade of Williams’ division, under the command of Brigadier General George H. Gordon, formed in reserve behind and to the right of Crawford’s Brigade. Additional Union batteries wheeled into place along Augur’s line, preparing to duel with the growing number of Confederate guns opposite them.23

Meanwhile, Ewell swung his other two brigades far to the right of Early, positioning them on the western slope of Slaughter Mountain. At around 2 PM the vanguard of Winder’s Division reached the field, its column having halted in the road while Ewell’s Division deployed. Winder and his staff rode forward along the Culpeper Road until they reached the point where the woods east of the road met the wheatfield. There, Winder could make out the Union batteries exchanging fire with Ewell’s guns. Seeing an opportunity to enfilade the Union artillery, Winder ordered all the rifled, long-distance guns of his command to be brought forward and massed at that point. He also directed Lieutenant Howard to guide the brigade led by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas S. Garnett into the woods west of the road, while the brigade led by Colonel Alexander G. Taliaferro was ordered to deploy east of the road in support of the artillery and the Stonewall Brigade was directed to remain in reserve. As aides scurried off with his orders, the general and his remaining staff began tearing down the fence along the Culpeper Road to allow the guns to roll into position.24

By about 2:30 PM Winder’s batteries were prepared to open fire. Their opening shots triggered a general artillery duel across the battlefield, the boom of the guns echoing through the Virginia countryside. “Soon the din of bursting shells… was quite appalling,” recounted a member of Winder’s staff, “made more so from the splintering of tree branches overhead.” As shells burst around him, Winder calmly directed the return fire. Still feverish, the general had removed his coat and rolled up his shirt sleeves. Gazing through binoculars, he called out range adjustments to the gunners as they zeroed in on the enemy guns.25

Winder shouted one of these corrections to the crew manning a Parrott rifled gun to his immediate right. Over the din, the artillerymen could not hear what he had said, and a gunner ran towards Winder to ask him to repeat the order. The general cupped his hands to his mouth and had shouted only a word or two when a shell passed between his left arm and his side, completely tearing away the flesh of the inside of his arm and lacerating the left side of his torso as far back as the spine. Winder “fell straight back at full length, and lay quivering on the ground,” according to an observer.26

A group of artillerymen placed the general on a stretcher. Lieutenant Howard had just returned from deploying Garnett’s Brigade and asked his fallen commander, “General, do you know me?” “Oh yes,” Winder replied, before he began muttering “My poor, poor wife” and mumbling of his children as “my little pets.” A surgeon galloped up, but quickly saw there was nothing to be done. A chaplain knelt at Winder’s side and said, “General, lift up your heart to God.” “I do, I do lift it up to him,” replied Winder. Within ten minutes of being hit, Winder slipped out of consciousness.27

As they carried the fallen general to the rear, the stretcher party passed by the Stonewall Brigade, drawn up in reserve with muskets stacked along the Culpeper Road. The men quickly recognized their commander and a crowd of officers formed around Winder’s stretcher. Lieutenant Howard watched as the enlisted men silently took “a last look at the leader who had so well won their confidence and attachment.” Captain Moore noted that the men of his unit “said nothing, but seem sternly to resolve that for every drop of his blood, they would pour out a gallon of Yankee blood.” The stretcher party continued on a short distance before stopping at a small grove west of the road. There, with Lieutenant Howard gently supporting his head, Winder gave his final breath.28

Private Casler, whose punishment Winder had ordered just a short time before, was among those soldiers who watched the stretcher pass with his mortally wounded commander. “His death was not much lamented by the brigade,” Casler claimed, “for it probably saved some of them the trouble of carrying out their threats to kill him.” Not everyone in the brigade, however, shared Casler’s embittered view of their fallen leader. A captain in the Fourth Virginia noted that Winder “was a most gallant soldier, and by his admirable discipline, was not only keeping the Brigade efficient, but was making it better, I think, than it ever was before.”29

The highest praise came from Jackson himself. In his official account of the battle, Jackson wrote, “It is difficult within the proper reserve of an official report to do justice to the merits of this accomplished officer. Urged by the medical director to take no part in the movements of the day because of the then enfeebled state of his health, his ardent patriotism and military pride could bear no such restraint. Richly endowed with those qualities of mind and person which fit an officer for command and which attract the admiration and excite the enthusiasm of troops, he was rapidly rising to the front rank of his profession. His loss has been severely felt.”30

Charge, Charge and Yell!

Winder’s death thrust Colonel Taliaferro into command of the division. Having no knowledge of what Winder’s plans had been, he rode forward to examine the position of Garnett’s Brigade. He found Garnett’s command, currently the only Confederate unit to the west of the Culpeper Road, deployed in an L-shape, part of the brigade facing the wheatfield and part parallel to the road. They were in an excellent position to enfilade any Union advance through the cornfield but were nearly 200 yards in advance of the main Confederate line and had no troops covering their left flank. Taliaferro rode past Garnett’s regiments and into the wheatfield, where he saw no sign of Federal activity. Confident that the battle’s main action would be against the Confederate right, Taliaferro rode back to next examine the position of the division’s artillery. He was soon overtaken, however, by an officer bearing word that Union skirmishers had appeared in the wheatfield just visited by Taliaferro. He immediately ordered the Tenth Virginia to be detached from his own brigade and sent to reinforce Garnett. He also sent word to Colonel Ronald to advance the Stonewall Brigade to the left of Garnett’s line.31

The enemy skirmishers spied by Garnett’s troops were from Crawford’s Brigade. With the artillery duel still sending waves of thunder across the battlefield, at around 4 PM Crawford advanced the Fifth Connecticut, the Twenty-Eight New York, and the Forty-Sixth Pennsylvania into the dense woods to the west of the Culpeper Road. The largest regiment of his brigade, the Tenth Maine, remained behind to support the artillery. The woods were choked with underbrush and sharp briars yanked at the men’s uniforms. Nearly impassible, the tangled woods prevented a man from seeing a person standing only a few yards away. Just before the Union regiments reached the edge of the woods, the brush began to thin, and Crawford ordered a halt along a narrow logging path which meandered through the timber. As officers rushed to dress the brigade’s line, Crawford removed his coat and sword and dropped to the ground. Crawling on his belly through the brush, Crawford made his way forward to the edge of the forest.32

Before him Crawford saw a wheatfield, the stubble of the freshly cut wheat dotted with neat shocks of cut grain. The eastern end of the circa 30-acre wheatfield was roughly 600 yards wide where it ran along the Culpeper Road. Roughly 800 yards to the west, the field, now only around 400 yards wide, came to an end. Farther to the west beyond the wheat was a second field, which had not been planted for several years and had become overgrown with scrub oak, dwarf chestnut, and other brush as high in some places as a man’s shoulder. This bushy field was about 125 yards wide, but over 500 yards long and covered about two acres. A high log fence separated the wheatfield from the woods in which Crawford’s men were now dressing their lines. The wheatfield rose gradually for about a third of its width and then fell gently to a slight hollow cut by a mostly dry creek bed. Beyond the hollow to the south, the ground rose more sharply to another high log fence. In the woods behind this fence lurked Confederate infantry, but Crawford was unsure of their strength.33

The general crawled back to his command and ordered it forward to the edge of the woods. As his men began to tear down portions of the fence, a sergeant led a small group of skirmishers from the Fifth Connecticut into the wheatfield. After making their way as far as the hollow, they soon returned, believing they had escaped detection. These men were, however, likely the ones spotted by Garnett’s men, prompting Taliaferro to order the advance of the Stonewall Brigade and thus dramatically alter the outcome of the brewing fight.34

Banks had originally ordered Crawford to advance through the woods and attack the enemy’s left with a single regiment. This regiment’s objective would be to silence the Confederate batteries positioned by Winder along the Culpeper Road. From his reconnaissance and reports from the Fifth Connecticut’s skirmishers, it was apparent to Crawford that the Confederates on the far side of the wheatfield were too numerous for a single regiment to rout. Instead, he obtained Banks’s approval to attack with his entire brigade. Crawford also requested a section of smoothbore Napoleon guns be brought up to support his assault and sought additional troops to cover his right flank.35

The soldiers from which Crawford sought help were six companies of the Third Wisconsin, part of the other brigade in Williams’ Division commanded by Brigadier General George H. Gordon. They had initially been dispatched as skirmishers in the woods north of the wheatfield to screen the front of Williams’ Division, spread out along a 500-yard line. Soon after Crawford’s men advanced through their skirmish line, Crawford sent word back requesting they join his attack. Colonel Thomas H. Ruger, commanding the Third Wisconsin, replied that he was waiting for orders from his own brigade commander and could not join the attack on his own initiative.36

Just before 5 PM, however, General Williams received word from Banks that a Union attack through the cornfield east of the Culpeper Road was having success and Crawford should attack immediately. A staff officer from Williams galloped up to Crawford and relayed the order to advance without delay. Guiding his horse along the narrow lane through the dense woods, the officer next came upon Lieutenant Colonel Louis H. D. Crane of the Third Wisconsin chatting with one of his company commanders. Stating that the six companies’ cooperation would be necessary to take the Confederate batteries and assure victory, the staff officer ordered the Wisconsin soldiers to join Crawford’s attack.37

Ruger began recalling his dispersed unit, reforming on one of his center companies. Marching his short battle line slightly to the right so as to bring them up on Crawford’s right flank, the colonel halted his men near the edge of the bushy field. Ruger informed his soldiers that a Confederate battery needed to be taken and that the honor of the regiment rested in their hands. After ordering them not to cheer or yell until they had broken the enemy, the command soon came—“Forward!”—and a moment later “Double quick!” as the Wisconsin soldiers charged into the bushy field.38

Meanwhile, urged by Banks to attack immediately, Crawford had not waited for the Third Wisconsin. In the Fifth Connecticut, Colonel George D. Chapman briefly reminded his men to remember their good name and do credit to their themselves and their state. Crawford’s command to fix bayonets was repeated up and down the brigade line. Then came the shouted order, “Charge, charge and yell!” Clambering over what remained of the fence with loud cheers, the brigade paused in the open wheatfield only long enough to dress its line and then surged across the stubble field. A Union officer watching the assault stated Crawford’s men “burst with loud cries from the woods, [and] swept like a torrent across the wheat-field.”39

Annihilation to Remain

About an hour earlier, Colonel Ronald had received Taliaferro’s order to advance the Stonewall Brigade to support Garnett’s left flank. Had the brigade advanced promptly, soon after Taliaferro had received word of Crawford’s men amidst the wheat shocks, the coming action might have proceeded very differently. Confusion in the Confederate command, however, would hinder Ronald’s advance. Jackson had retained most of his divisional staff when he became a de facto corps commander and Winder had relied on the Stonewall Brigade’s staff during his less than twelve hours in command of the division. Now, much of that staff had departed with their slain leader, forcing Ronald to rely on Captain John H. Fulton of the Fourth Virginia and Major Fredrick W. M. Holliday of the Thirty-Third Virginia as acting aides. Officers from multiple staffs galloped across the field, relaying contradictory orders of unknown origin.40

Ronald deployed the Stonewall Brigade in a line of battle perpendicular to the Culpeper Road and ordered his men to load their weapons. The Twenty-Seventh Virginia anchored the brigade’s right flank along the road, followed to the left by the Thirty-Third Virginia and then the Fifth Virginia. Next came the Second Virginia, with the Fourth Virginia forming the brigade’s left flank. No sooner had Ronald directed the line to advance through the woods towards Garnett’s position when orders arrived to change the brigade formation into a column of regiments. Although unsure from whom this order came, Ronald dutifully halted his advance and formed a column led by the Twenty-Seventh Virginia. Just as he was about to again order the advance, another staff officer galloped up with orders to revert back to a line of battle. The almost certainly frustrated Ronald once again changed the brigade’s formation and ordered the advance before any further orders could arrive.41

Marching through the dense forest, the Stonewall Brigade soon came under “a heavy fire of spherical case and canister shot” from Union batteries shelling the woods. Leaves showered down on the men as the savage lead ripped through the branches over their heads. A shell fell amidst the Fifth Virginia, causing six men to fall either dead or wounded. An officer rushed over to the bloody gap in the line, calmly and firmly calling out “Steady, men, steady! Close up!”42

The Stonewall Brigade, marching diagonally to the right behind Garnett’s line, eventually reaching a fence running along the southern end of the bushy field, roughly 600 yards from the Culpeper Road. Ronald called out a halt and then directed that the men begin tearing down the fence. His soldiers thus occupied, the colonel dispatched Captain Fulton to report the brigade’s position to Taliaferro and seek additional orders. The brigade’s regimental and company officers busied themselves in straightening the line and the men caught some rest in the cool shade of the trees. About twenty minutes later, Fulton returned with orders from Taliaferro to continue the advance. Because the bushy field went farther south than the western end of the wheatfield, Ronald’s line was still a few hundred yards behind Garnett’s flank, leaving a dangerous gap in the Confederate line which Taliaferro wanted filled as soon as possible.43

A mounted Ronald led the Stonewall Brigade forward into the bushy field. As the brigade line was longer than the width of the field, only the Second and Fifth Virginia were entirely in the open. On the left, the Fourth Virginia was mostly within the woods west of the field. To the right, the Twenty-Seventh Virginia was entirely in the woods, moving up towards the left flank of Garnett’s Brigade. Half of the Thirty-Third Virginia was also concealed in the trees, while the regiment’s left wing spilled out into the cleared field.44

Like the adjacent wheatfield, the southern end of the bushy field dipped down to a small depression before climbing to a slight rise near the middle of the field. As the Stonewall Brigade began to march steadily up the gentle slope of this rise, Ronald rode forward alone to see what lay concealed on the other side of the elevation. Cresting the rolling ground, the colonel suddenly saw a line of Union infantry just 300 yards away, advancing directly towards him. Wheeling his horse and galloping back towards his men before he could be spotted, Ronald shouted for them to prepare to open fire.45

The troops discovered by Ronald were the six companies of the Third Wisconsin, advancing alone across the bushy field. Although they had intended to move forward alongside Crawford’s men, they had been delayed as they moved at the right oblique through the snarl of undergrowth. Colonel Ruger also misjudged the length of Crawford’s line, causing the six companies to move well to the right of Crawford’s last regiment. The Midwesterners scaled the high rail fence and, pausing only briefly to reform their line, advanced alone into the bushy field.46

Suddenly, in front of them, a solid line of Confederate infantry appeared, stretching all the way across the field beyond the flanks of the isolated Third Wisconsin. As the Stonewall Brigade crested the small rise in the middle of the field, it appeared to the Union soldiers “as though they arose from out of the ground.” The Confederates gave the startled Union soldiers no time to react, letting loose a volley which an officer in the Second Virginia later judged was “one of the most effective that he ever saw delivered in a battle.” The men of the Third Wisconsin would have agreed, with one of the Union officers on the receiving end of the volley calling it the “the most destructive fire that I experienced in the whole course of the war.”47

On the left of the Stonewall Brigade’s line, the Fourth Virginia enjoyed both the protection of the trees and a slight advantage in elevation. Only puffs of gun smoke marked the regiment’s position to the Third Wisconsin. With no enemy directly to his front, Gardner threw his left flank forward and wheeled his command to the right, enfilading the Union flank from a distance of only some 20 yards. The left wing of the Second Virginia followed suit, wheeling to bring additional fire on the suddenly beleaguered Union right flank.48

The rightmost companies of the Third Wisconsin were hardly in a position to effectively respond. Their advance through the woods having been slowed by an encounter with a patch of blackberry briers, the Wisconsinites’ right wing still lagged slightly behind the regiment’s left wing when the firing began. One of the Federal soldiers judged that “under such a concentered fire it was annihilation to remain. Men were falling by scores each instant.” Captain William Hawley, commander of Company K on the far right, fell wounded in the first volley with a bullet through the ankle and began limping to the rear. “It hardly seemed a minute,” recalled one of the regiment’s other company commanders, “before all of Co. K and nearly all of F were back again in the woods.” Lieutenant Colonel Crane tried to steady the right of the line “while the storm of bullets rained through the cloud of smoke in front.” Astride a nervous roan horse which “kept him busy trying to stay on its back,” Colonel Ruger rode back and forth trying to rally his men. Seeing his right flank melt away, he called on his men to retreat to the protection of the woods.49

Noting that his command’s volleys had disrupted the Union regiment before him, Colonel Ronald judged the time was right for a charge. In clear voice he called out “First Brigade, prepare for a charge bayonet!” Forward went the Virginians, emerging like demons with a “terrible yell” from the smoke of their most recent volley. As they surged forward, Crane galloped across the brigade’s front, endeavoring to rally his retreating men. Calling for the Wisconsin regiment to reform behind the fence, he slowly turned his small dark cream-colored horse through a gap in the barrier. In the Second Virginia, Captain Moore called out for one of the members of his Company I who had a reputation as a marksman. A crack, a puff of smoke, and the Union officer fell from his horse, killed instantly.50

With the enemy fleeing before him, Colonel Ronald must have been pleased with the outcome of his first combat experience as a brigade commander. Spotting the Third Wisconsin attempting to rally in the trees behind the fence, Ronald began to prepare a second charge to sweep the Midwesterners entirely from the field. Just as he was about to order the coup de grace, however, troubling news reached Ronald from his right flank.51

The fight in the bushy field had been brief and lopsided. The six companies of the Third Wisconsin were entirely outmatched by the combined firepower of almost an entire brigade. The three rightmost companies were hit particularly hard, with more than a third of their number falling killed or wounded. Two hundred and seventy-six men of the Third Wisconsin had marched into the bushy field and, in an encounter which one Union participant estimated lasted a mere two minutes, they had left eighty of their number killed or wounded amidst the scrub oak. Although Ruger had escaped unharmed, Crane’s corpse lay next to the fence and the regiment’s major had taken a ball through the shoulder, crippling his left arm for the remainder of his life.52

Jackson Will Lead You

When Ronald had ordered the Stonewall Brigade to attack the Third Wisconsin, only his left and centermost regiments had been able to comply. While the left wing of the Thirty-Third Virginia joined in the brigade’s opening volleys, the remainder of the regiment and the entirety of the Twenty-Seventh Virginia continued to struggle through the fallen timber, thick undergrowth, and dense trees flanking the bushy field. As half of his Thirty-Third Virginia opened fire, Colonel Lee’s horse became excited, forcing Lee to proceed on foot as his men joined in the brigade’s advance.53

As the Wisconsin soldiers fell back, the right wing of the Thirty-Third Virginia finally emerged from the trees at the southwestern edge of the wheatfield. With his full regiment now exposed to enemy view, Lee halted his men behind the wheatfield’s fence and commenced firing at the retreating Third Wisconsin.54

Suddenly, shouts came from Company A on the far right of the regiment. Federal troops were in the trees on the Thirty-Third Virginia’s right flank, less than 40 paces from Company A and in a position to bring a devastating enfilade fire to bear on the regiment. Lee shouted for his three right companies, Companies A, F, and D, to immediately refuse the line, drawing them back at a right angle to protect the regiment’s flank. He then dispatched his adjutant, Lieutenant David H. Walton, to ensure the Twenty-Seventh Virginia was aware of this new threat. Walton soon ran back to report that the regiment, which only moments before had been just to Lee’s right, was nowhere to be found.55

The Twenty-Seventh Virginia had gotten caught up in the Union assault that had swept like a cyclone across the wheatfield moments before the Stonewall Brigade routed the Third Wisconsin. Crawford’s Brigade had charged from the northern woods with a yell, the Forty-Sixth Pennsylvania on the right, the Twenty-Eight New York in the center, and the Fifth Connecticut on the left. The Union soldiers surged over the rail fence on the Confederate side of the wheatfield and smashed into Garnett’s Brigade with little warning. The Confederates’ attention had been occupied by a Union brigade making an attack through the cornfield to the east of the Culpeper Road. “We pushed the fence over on them,” reported an officer in the Twenty-Eight New York, “which was the first warning they had.”56

“The storm,” noted a Union observer, “burst suddenly upon the enemy.” Garnett’s command crumbled in a brief melee of hand-to-hand fighting. The Tenth Virginia, dispatched earlier to reinforce Garnett’s left flank, could only briefly slow the Forty-Sixth Pennsylvania before they too were forced to fall back. A Union officer watching the assault observed how Garnett’s Brigade “had been thrown, helpless and confused, into a disordered mass, over which, with cries of exultation, our troops poured, while field and woods were filled with clamor and horrid rout—poured like an all-destroying torrent, until the left of Jackson’s line was turned and its rear gained.”57

Advancing through the woods just to the left of the Tenth Virginia and Garnett’s left flank, the Twenty-Seventh Virginia suddenly discovered the troops to their right had melted away. With refugees from Garnett’s Brigade and the Tenth Virginia streaming through their formation, the Twenty-Seventh’s line began to waver. As the Forty-Sixth Pennsylvania crashed against their flank and rear, Captain Haynes found his regiment caught in a crossfire. At risk of being cut off and overrun, Haynes ordered his men back. With the thick underbrush and fallen timbers further scattering the Virginians, the retreat quickly became a rout as the Twenty-Seventh Virginia fled through the trees.58

Running through the forest back towards the Culpeper Road, the broken Twenty-Seventh Virginia streamed through the ranks of Confederate reinforcements advancing to plug the gap which Crawford’s assault had ripped in Jackson’s line. Brigadier General Lawrence Branch, commanding the advancing Confederate relief, wrote after the battle that “I had not gone 100 yards through the woods before we met the celebrated Stonewall Brigade, utterly routed and fleeing as fast as they could run.” Branch’s report would later lead to false claims that the entire Stonewall Brigade had been routed at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, whereas in reality the Twenty-Seventh Virginia was the only portion of the brigade which broke.59

As he neared the Culpeper Road, Captain Haynes began to regain control over some of his scattered and panicked men. Among the mass of soldiers was Lieutenant Edgar, the same young officer who had attempted to consume four apple pies prior to boarding the trains in Richmond. “At this critical moment, Stonewall Jackson gallops up to us in a most excited manner and draws his sword,” recounted Edgar. “I am within ten feet of him and see and hear him distinctly. He shouted ‘Rally brave men. Rally and follow me. Jackson will lead you.’ We rallied and pressed forward. Our line was soon restored. Jackson rode along the front and shouted, ‘Give them the bayonet! Give them the bayonet! Forward and drive them!’”60

Jackson’s personal intervention to rally the Twenty-Seventh Virginia and the other Confederate units routed by Crawford’s assault is shrouded in layers of legend. None of the accounts from the Stonewall Brigade recount the famous story that Jackson’s sword had rusted in its scabbard, forcing the general to instead wave the sheathed weapon while rallying his troops. Lieutenant Edgar’s eyewitness account explicitly stated Jackson drew his sword. Captain Haynes, in his official report submitted just days after the battle, confirmed Jackson’s role rallying the Twenty-Seventh Virginia. The men of the regiment, Haynes recounted, gave a cheer at Jackson’s approach and “at the personal order of General Jackson followed him again to the battlefield.”61

The Union wave, meanwhile, had begun to loss its momentum. Men of the Twenty-Eight New York, led by the regiment’s adjutant, advanced as far as the Confederate batteries along the Culpeper Road before the adjutant fell dead alongside one of the guns. But Crawford’s units had lost all semblance of order in their melee with Garnett’s Brigade. What officers remained in the Union brigade struggled to rally and reform their men in the tangled underbrush as they faced a determined Confederate counterattack by Branch’s Brigade and the fragments of the Twenty-Seventh Virginia and Garnett’s Brigade rallied by Jackson. The greatest danger, however, would come from the remainder of the Stonewall Brigade.62

Deliberately into a Fiery Furnace

Back in the bushy field, Ronald had been about to order his brigade into the woods hot on the heels of the Third Wisconsin when he learned of the collapse of his right flank and the rout of Garnett’s command. With the Twenty-Seventh Virginia swept away, the Thirty-Third Virginia became the new right flank of Ronald’s command. The three rightmost companies that Lee had drawn back at a right angle immediately opened fire on the Forty-Seventh Pennsylvania. “In a few moments the ground was dotted with their blue uniforms,” reported Lee with satisfaction.63

Since the Third Wisconsin had disappeared back into the thick woods beyond the bushy field, Ronald concluded that the threat to his right was more pressing than that from the retreating Midwesterners. He ordered the Second Virginia and Fourth Virginia to guard against any any renewed advance from the Third Wisconsin, dispatching a single company of skirmishers from the Second Virginia, under the command of Captain Moore, forward into the woods as a screen. He then called for the Fifth Virginia to pull back and support the brigade’s beleaguered right while the Thirty-Third Virginia conducted a change in front, wheeling to the right to the new line established by Lee’s three rightmost companies. This new formation would bring the regiment out of the bushy field and stench their battle line across the western edge of the wheatfield perpendicular to their original line, supported by the Fifth Virginia and with their left flank covered by the Fourth and Second Virginia.64

Major Holliday, temporarily acting as an aide to Ronald, relayed the order to advance to the left wing of the Thirty-Third Virginia. Seeing some of the men hesitating to advance into the open wheatfield, the major yelled to the regimental color bearer, “Get over the fence and I know the men will follow!” The color bearer sprang forward over the obstacle, followed closely by the rest of the regiment. A shot rang out and the color bearer fell to the ground. The battle flag had barely touched the ground before another man leapt forward to raise the banner.65

As his company wheeled with the Thirty-Third Virginia, Captain White paused a moment to take in the vista before him. “The scene on the battle field was more like the pictures of battles than any I had ever witnessed. As we, on the left, moved forward and gained the top of a ridge before us, we could see the line of battle extending around to the extreme right, all along which the smoke rolled up in great clouds, and fire from the two sides flashed fiercely at each other. I did not have time to look long at this scene, for a little smoke, and some fire too, nearer at hand engaged my attention.”66

Major Williams, ordered to fall back and support the brigade’s right, had halted his men and was just about to order the about face when he discovered that his regiment was now in the rear of the Federal line engaged by the Thirty-Third. Rather than following Ronald’s order to pull back, Williams took the initiative to wheel forward and advance to the left of the Thirty-Third. With Williams’ decision, Crawford’s position was rapidly becoming untenable. Caught between Branch’s Brigade to their front and the Stonewall Brigade suddenly appearing on their right and rear, the Union soldiers could soon be cut off and surrounded. “Nothing was left for the gallant few but to find their way to the rear across the wheat field as best they could,” recalled one of the Connecticut soldiers in Crawford’s command. “Slowly at first, more rapidly afterwards, they fell back by the way of their advance.”67

As the blue-clad soldiers began to stream back across the field, the Thirty-Third and Fifth Virginia’s volleys cut them down like wheat before the scythe. The Union retreat through the open field “exposed his broken columns to a deadly cross-fire from Branch’s and this brigade,” reported Ronald. “Pen and thought combined cannot do this subject justice,” recalled a captain in the Fifth Connecticut struggling to convey the perilous situation. “It was as if the men had deliberately walked into a fiery furnace and I only wonder how many escaped from certain death upon that field.” A Union soldier elsewhere on the battlefield described hearing “the most tremendous volleys we had ever heard. Crash succeeded crash; the mighty thump of the shells against the forest trees was not heard for the din of the musketry.”68

Within moments, the Stonewall Brigade began to decimate the fleeing Federals. A shot from an unknown Virginian mortally wounded Colonel Donnelly, commander of the Twenty-Eight New York, just before the officer could reach the safety of the far wood line. Donnelly was taken from the field by his orderly supporting the dying man on his horse. The Fifth Connecticut’s Major E. W. Blake, who had that morning dressed in a brand-new uniform, fell dead somewhere amidst the wheat. The Forty-Seventh Pennsylvania’s Colonel Joseph F. Knipe also fell, severely wounded.69

With Union men and officers dropping by the dozen, Major Williams now ordered the Fifth Virginia to charge forward into the confused Union ranks. As the Virginians’ line surged forward, Color Sergeant John M. Gabbert raced several paces in front of the regiment, holding the regimental colors in one hand and waving a sword in the other as he shouted for the men to follow him. Moments later, he tumbled to the ground, shot in both the shoulder and leg. Carried from the field, Gabbert would die of his wounds the following month.70

The Fifth Virginia smashed into the mass of fleeing men, capturing scores. A young man in the regiment chased down a fleeing Union soldier, grabbing him by the belt. Another soldier smashed his musket butt against the head of a Connecticut captain, throwing the officer to the ground and taking him captive. Colonel George D. Chapman, commanding the Fifth Connecticut, had already been briefly captured during the melee with Garnett’s Brigade in the woods, but had gotten free. As the Fifth Virginia surged forward, Chapman found himself surrounded. A handful of his men rallied and sallied forth to rescue their commander but failed to reach him before he fell into Confederate hands.71

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Edwin F. Brown, briefly in command of the Twenty-Eight New York after Colonel Donnelly suffered his mortal wound, had his left arm shattered by a musket ball. Advancing Confederates captured the grievously wounded officer and began to march him to the rear under guard. As the Union officer and his escort made their way back through the wheatfield, a private in the Fifth Connecticut, lying on the ground wounded in both legs, fired a final shot at the Confederate soldier escorting Brown. Seeing his captor fall at his feet, Brown turned and began to make his way back towards the Union side of the wheatfield. Bleeding profusely from his wounded arm, Brown collapsed short of the trees and laid there until a corporal braved the Confederate fire to run forward and drag Brown to safety. Brown spent that night in a field hospital and his arm was amputated the following day.72

Along with their prisoners, the Fifth Virginia also captured at least two and probably three stands of Union colors. Major Williams reported his command captured three Union flags and some members of the regiment later claimed all three had been captured by a single man, Corporal Narcissus F. Quarles. If this lone soldier did achieve this improbable feat, Quarles had little time to boast of his accomplishment, as he would be dead on the fields near Manassas by the end of the month. Confusingly, Ronald’s report stated the Fifth Virginia captured two colors. He claimed a third flag had been captured but was improperly taken from a private of the Stonewall Brigade by an officer from some other brigade. Jackson’s report, however, credited all three flags to the Stonewall Brigade and identified two of these colors as having belonged to the Fifth Connecticut and Twenty-Eight New York.73

Union accounts do not further clarify the matter. General Williams went out of his way to state in his report that Crawford’s Brigade retained all their colors. Crawford’s own report is silent on the issue, only stating that the Fifth Connecticut’s banner had been shot down three times. However, the Fifth Connecticut’s regimental history freely admitted that their colors were captured by the Fifth Virginia, after at least five previous color bearers had been killed or wounded. A battle account written by a member of the Third Wisconsin further confirmed that the Fifth Connecticut and Twenty-Eight New York both lost their colors.74

Perhaps causing some of the confusion, at least the Fifth Connecticut also carried a state flag, which survived the fight after its twice-wounded color bearer wrapped the flag under his bloody uniform and crawled back to safety. The third captured flag may have been a state flag belonging to the Twenty-Eight New York, which would explain why Jackson’s report mentioned three flags but then only identified two regiments. If it was from a third unit, the Forty-Sixth Pennsylvania would be a top candidate, particularly as they were on the end of the Union line closest to the Stonewall Brigade when the Fifth Virginia charged. No sources explicitly discussed the fate of the Pennsylvania regiment’s colors and it is also possible the flag was captured from a completely separate Union unit during the final Federal retreat later in the battle.75

The losses in Crawford’s three regiments were devastating. Every single field officer and adjutant in the three regiments had been killed, wounded, or captured. The Twenty-Eight New York lost all of its company officers, while the Fifth Connecticut had only eight junior officers remaining, and the Forty-Sixth Pennsylvania could muster only five company commanders after the fighting. Of the just over 1,300 men and officers who advanced across the wheatfield, 694 became casualties. Advancing Confederates had captured 370 Federal men and officers, many by the Fifth Virginia. The day’s battle was the greatest loss the Fifth Connecticut suffered during its four years of service and was one of the top three deadliest days for any Connecticut regiment during the entire war. Crawford’s official report paid a grim tribute to his men’s losses; “The vacant place of my officers and the skeleton regiments of my brigade… speak more earnestly than I can do of the part they played in that day’s content.”76

Bullets Going Past in Sheets

With three of his regiments routed and being cut to pieces by the Stonewall Brigade, Crawford still had one card left to play. His fourth and largest regiment, the Tenth Maine, had remained behind supporting artillery batteries near the center of the Union line when the rest of Crawford’s brigade went forward. Soon after Crawford unleased his men across the wheatfield, he ordered the Tenth Maine to advance into the woods north of the wheatfield. Their left resting near the Culpeper Road, the Union regiment lay in the cover of the trees while their comrades were locked in struggle on the other side of the wheatfield.77

With the rest of Crawford’s Brigade now fleeing from the field, a staff officer from Banks galloped up and ordered Colonel George L. Beal to advance his regiment to cover the retreat. Only knowing that his brigade was somewhere in front, Beal got the Tenth Maine to its feet and ordered the men forward. As the Maine men picked their way through the tangled undergrowth, the occasional Confederate artillery shell ripped through the trees overhead. One shell scored a direct hit on a tree just in front of the regiment, sending the tree crashing to the ground and forcing Companies B and D to maneuver around the obstacle.78

The Tenth Maine emerged from the woods and spilled into the wheatfield. Mounted and riding in front of his men, Colonel Beal swung his hat over his head and called out “Give them three down-east cheers!” His men advanced with a yell, surging forward through the stubble. As they crested the small rise in the middle of the field, however, they were presented with a grim sight. The shattered remnants of their sister regiments streamed by to their right, running to escape the Confederate volleys sweeping the field. As they ran by, panicked fugitives from the decimated units called out to Beal that there were too many Confederates for the Maine men to handle. Seeing the woods in front of him swarming with ever increasing numbers of Confederates, Beal prudently ordered his men to face to the rear and march back behind the protection of the rise.79

The regiment had gotten only a few steps when Major L. H. Pelouze, one of Banks’s staff officers, galloped up and shouted for the men to halt. He screamed that Banks forbade the retreat and that they should instead face the enemy and attack. Colonel Beal ignored Pelouze and directed his men to continue their withdrawal. Infuriated, Pelouze yelled at Beal to turn his men around, punctuating his words with such animated gestures that to the enlisted men it appeared as if the staff officer was in a fist fight with their colonel. Beal waited until his men had gained a degree of protection behind the ridge slope and ordered them to face about and open fire. The sole Union unit still intact in the immediate area, the Tenth Maine would stand and sacrifice itself to gain time for the rest of its brigade to reach safety.80

Confederate fire began to rip through the regiment even before it halted. Sergeant John M. Marston of Company F, a former English marine acting as the left general guide on the flank of the regiment, was one of the first to fall. Captain Andrew C. Cloudman, working to properly align his Company E, dropped dead as a musket ball smashed through his skull. Within moments, the unheeded Major Pelouze fell wounded as well. As each man successively got into position, they opened fire without waiting for orders. A Maine veteran recalled “the bright sunset dazzling our eyes and adding another drop to our bucketful of disadvantages” as the sun set behind the trees directly in front of the Union regiment. From the growing shadows, the blaze of muskets marked the Confederate positions.81

“Their bullets began to fly and our line began to wilt in a way none of us ever knew before or since,” recounted the unit’s adjutant Lieutenant John M. Gould. There were so many wounded men withering in agony that “it looked as if we had a crowd of howling dervishes dancing and kicking around in our ranks.” Seeking what cover they could, some of the Federals dropped to their knees to load and fire, while others hugged the ground on their stomachs. The single regiment was absorbing the fire of more than three Confederate brigades, with the Stonewall Brigade enfilading their right flank and the woods to their front swarming with Branch’s Brigade and rallied squads from the Twenty-Seventh Virginia and Garnett’s Brigade. Confederate bullets seemed, to Lieutenant Gould, to be “going past in sheets, all around and above us.”82

Finally, Beal spotted Union skirmishers coming up at a run to the right of the Tenth Maine. Behind them, about 300 yards away he could make out a line of fresh Federal regiments. His men falling all around him, Beal shouted for his men to retreat. “The carnage in our ranks during the few seconds preceding this order,” recounted Gould, “was terrible and altogether beyond description. There were huge gaps in our lines – more places for bullets to go through, it is true – yet it seemed as if the rebels were cooling down, and taking deliberate aim now, and of course they were less annoyed from our fire, as our numbers decreased.”83

Over the din of battle, not all the men heard the order to retreat, and the Tenth Maine’s formation broke up as they pulled back towards the safety of the woods. As their officers worked to keep their men together, the Maine soldiers generally gathered around their colors. By this point in the battle, the banner was held aloft by a corporal, who had taken the flag after the color sergeant fell wounded. The entirety of the rest of the color guard lay dead or wounded on the field alongside many of their comrades.84

Afterwards, the Maine men could not agree on how long they had been caught in the maelstrom of the wheatfield. Beal’s report stated they had been in the field around 30 minutes, but some men said it had been as little as five minutes. Some men had only fired five or six cartridges and few had used up more than the 20 rounds held in the top of their cartridge boxes. However brief their engagement, the stand of the Tenth Maine had bought valuable time, but at a devastating cost. The regiment had advanced with 26 officers and 435 men. Now, 39 members of the regiment lay dead or mortally wounded, with another 134 wounded and six taken prisoner.85

An Unbroken Roar

The Union troops who had advanced to the relief of the Tenth Maine were part of the other brigade in Williams’ Division, commanded by Brigadier General George H. Gordon. They had spent the battle thus far in reserve near the pretty white cottage and picket fence of the Brown Farm, on a ridge roughly a mile west of the Culpeper Road. There, the men had broken ranks and spent the afternoon laying in the shade, napping, brewing coffee, or watching the battle unfold before them. The female and child occupants of the farm nervously asked General Gordon what they should do, repeating their question without waiting for an answer. Despite Gordon’s admonition that they should flee the area at once, they refused to leave.86

While the rest of the brigade rested, Gordon had dispatched six companies of the Third Wisconsin forward as skirmishers into the woods on the other side of Cedar Run. These men would soon face the Stonewall Brigade alone in the bushy field. Fearing possible movement by Confederate cavalry around the Union right flank, Colonel Silas F. Colgrove of the Twenty-Seventh Indiana dispatched two companies of his regiment to a hill about a half mile away which offered a clear view of the surrounding area. These men would never be engaged and, in the panic of the ultimate Union withdrawal, they would be forgotten. The orphaned companies would only rejoin their regiment late that night, after having taken a circuitous route to avoid encountering the advancing Confederates.87

As he prepared to send Crawford’s Brigade forward at around 5 PM, General Williams had sent word to Gordon that he should be prepared to support Crawford’s attack if necessary. Williams told Gordon to watch him closely and, should Gordon see him signal by waving his handkerchief, Gordon should advance with his whole brigade. Gordon reformed his men, establishing his battle line near the Brown Farm with the Twenty-Seventh Indiana on the right, the Second Massachusetts on the left, and the remaining companies of the Third Wisconsin in the center. Gordon kept his field glasses locked on Williams as the sound of Crawford’s assault grew to a crescendo. To the men of the Twenty-Seventh Indiana, the musketry here at Cedar Mountain sounded “unusually energetic and terrifying.”88

As the sounds of fighting swelled, Gordon became increasingly impatient. He put down his field glass briefly at around 6 PM when a messenger rode up from Banks with orders to dispatch the Second Massachusetts to support the Union center. Gordon promptly gave the order and the regiment had just begun to march off to the left when one of Williams’ aides galloped up. “General Williams directs you to move your whole command to the support of General Crawford,” relayed the aide. Reflecting later, Gordon judged that he had likely missed Williams’ signal during the time he was dealing with Banks’s order.89

Perhaps because he was impatient to get into the fight or perhaps because he was embarrassed to have missed his cue, Gordon decided to advance with all possible speed. “Forward, double-quick!” came the order and his men surged forward, running down the slope of the hill and splashing through Cedar Run. On the opposite bank the ground rose rapidly into the thick woods which separated them from the wheatfield. Broken with ravines, ledges of rock, and loose stones, the men struggled to get through the woods just as much as the Third Wisconsin and Crawford’s men had earlier. “Trees and low bushes stand thick, with fallen tops and limbs and a tangle of vines and briars in many places, next to impenetrable,” recalled an Indiana soldier.90

Officers were soon urging Gordon to slow the advance, warning him that the men could not keep up this pace for much longer. The distance from the Brown Farm to the edge of the wheatfield was a bit over three quarters of a mile, 400 yards of which was through the woods. One of the officers judged the fact that the men were able to cover this distance “all at a double quick, with any one able to stand on his feet at the end of it is more than incredible – it is miraculous.” Ahead, however, Gordon could see “a thick smoke curling through the tree-tops, as it rose in clouds from corn and wheat fields, marked the place to which we were ordered—the place where the narrow valley was strewn with dead.”91

Panting and out of breath as they ran through the trees, the Twenty-Seventh Indiana abruptly stumbled upon a few scattered Confederates. These were the members of Captain Moore’s Company I of the Second Virginia, dispatched as skirmishers in the woods while the remainder of the brigade wheeled into the flank of Crawford’s retreating columns. The thick underbrush meant that the Union regiment was almost on top of Moore’s position before the Federals discovered his presence. Moore shouted for his men to fire, causing several Hoosiers to fall amidst the brush. The Federal regiment recoiled, retiring briefly in the face of an enemy whose strength they could not determine. But soon they pushed on, driving Moore’s men back towards the rest of the Stonewall Brigade.92

About 300 yards into the woods, Gordon’s men stumbled upon the rest of the Third Wisconsin. Most of the six companies which had clashed with the Stonewall Brigade had reformed near Cedar Run, passing around the flank of the Twenty-Seventh Indiana and rejoining the Third Wisconsin as Gordon’s Brigade sprinted by. Most of Company D and I, along with some men from Company F, C, and H, however, had been rallied in the woods by the wounded Captain O’Brien. He had led them down the wood lane a short distance to the cover of a little ravine. There, as the men reformed, a soldier helped O’Brien bind his wounded thigh with a handkerchief. Blood had run down the officer’s leg and filled his shoe, but O’Brien refused to head to the rear. As Gordon’s line passed through the woods, Colonel Ruger ordered O’Brien’s small band back into the ranks. Their fight was not yet over.93

“Red in the face, panting for breath, almost ready to drop down with heat and fatigue,” Gordon’s men finally reached the edge of the wheatfield. Gordon’s line had become disorganized and scattered by the run through the woods, with portions of the regiments lagging and many men still making their way forward to the new battle line. The brigade emerged into the northwestern corner of the wheatfield, the Twenty-Seventh Indiana’s right flank near where the wheatfield gave way to the bushy field and the Second Massachusetts about 300 yards from the now rapidly retreating Tenth Maine.94

About 400 yards away, Gordon could make out heavy Confederate battle lines emerging from the trees into the wheatfield. These were Branch’s men, along with the soldiers rallied by Jackson and a freshly arrived brigade under Brigadier General James J. Archer. The Stonewall Brigade was to Gordon’s left, likely opposite the Twenty-Seventh Indiana. This unit reported that a Virginia regiment was to their immediate front, almost certainly one of Ronald’s regiments, while fire the Hoosiers took from the bushy field probably also came from members of the Stonewall Brigade.95

In his report, Ronald does not specify how he repositioned his line to deal with Gordon’s advance. After the rout of the Third Wisconsin, he had kept the Second and Fourth Virginia facing towards the woods and these regiments most likely were the primary forces opposing Gordon in this sector while the remainder of the brigade rallied. Gardner noted that his Fourth Virginia had become somewhat scattered while engaging Crawford and needed to fall back a short distance and reform. The chaos of their successful melee with Crawford’s men had scattered the Fifth Virginia. When Major Williams ordered his men back, part of his command had advanced too far into the field in pursuit. The regimental adjutant had to rally the left wing of the regiment to the colors and Major Williams reformed his victorious regiment behind the fence line at the end of the bushy field. Farther to the right, firing had died down near the Thirty-Third Virginia, so Lee pulled his unit back 100 yards to collect men who had become “somewhat scattered in the eagerness of the fight” with Crawford’s regiments. After rallying his men and gathering parts of some other regiments, Lee advanced to rejoin Ronald and the rest of the Stonewall Brigade as they opened fire on Gordon’s newly arrived troops.96

One of the first volleys from the Stonewall Brigade smashed into the Twenty-Seventh Indiana and “seemed to mow down a dozen or so men” of the color company. The Twenty-Seventh Indiana and the Third Wisconsin immediately opened fire, but Gordon heard only silence from the left end of his line. Riding over, he discovered that the Second Massachusetts had veered farther to the left, creating a gap between them and the Third Wisconsin. “Why don’t you order your men to fire?” Gordon shouted to Colonel George L. Andrews, commander of the Massachusetts unit. “Don’t see anything to fire at,” replied Andrews. A likely frustrated Gordon ordered Andrews to move his regiment by the right flank and close the gap with the Third Wisconsin, telling him “You will soon find enough to fire at.”97

Soon the Second Massachusetts, firing by files, added their muskets to the fire of their sister regiments. The fire now, noted a member of the Bay State regiment, became “an unbroken roar.” “There was no intermission,” observed Gordon, “the crackling of musketry was incessant.” Lieutenant Colonel Lee noted that the men of his Thirty-Third Virginia kept firing until they had emptied their cartridge boxes and stated, “their aim was steady and their fire effective, inflicting under my own eye severe loss upon the enemy”. The Confederate fire soon began to show its effect on the line of blue. A bullet struck Colonel Andrew’s horse in the shoulder, followed soon after by another ball in the neck. The wounded horse reared, sending Andrews flying back into the branches and underbrush. In the Third Wisconsin, Captain O’Brien remained at the head of his company despite the blood pouring down his leg from the wound he had suffered in the bushy field. Now, a second bullet struck his body, dropping the officer for a second time. He would spend that night laying alone on the field in agony before being found by a Union burial party the next day. O’Brien would die later that day on the porch of a Culpeper hotel requisitioned as a hospital.98

With his regiment facing a Confederate force many times larger, Colonel Andrews received a puzzling order from Banks. A staff officer rode up to Andrews and ordered him to charge the Second Massachusetts across the wheatfield. A stunned Andrews replied “Why, it will be the destruction of the regiment, and will do no good!” The staff officer simply shrugged. Andrews relayed the order to Gordon, who told him to simply ignore it. Later it came to light that the order was delivered in error, as Banks believed the Second Massachusetts was located near the Union center, where he had ordered it dispatched just before Gordon advanced.99

Gordon, however, was also soon in receipt of a puzzling order from Banks. A member of the commanding general’s staff came up to Gordon and stated, “General Banks wishes you to charge across that field.” What field?” asked an incredulous Gordon. “I don’t know,” replied the man, “I supposed this field.” “Well sir,” shot back Gordon, “‘suppose’ ‘won’t do at such a time as this. Go back to General Banks and get explicit instructions as to what field he wishes me to charge over.”100

Meanwhile, the Twenty-Seventh Indiana spotted large bodies of troops maneuvering in the bushy field past their right flank. In the dying evening light, the uniforms of these soldiers appeared to be blue. “We are firing upon our own men!” shouted some of the Hoosiers. Colgrove relayed the concern to Gordon and asked whether he should cease fire. “We have no men there,” replied the general, “the enemy is there. Order your men to open fire upon him.” Seeing Colgrove was still hesitant least he fire on friendly troops, Gordon directed his horse past the end of Colgrove’s line. Gordon had just reached the edge of the bushy field when he “received a fire that settled the matter at once.”101

The fire likely came from portions of the Stonewall Brigade advancing in the bushy field. From their position on the right flank of Gordon’s Brigade, the Virginians poured fire into the Twenty-Seventh Indiana. Colgrove rode back and forth on his horse, “apparently oblivious of the storm of bullets that hissed about him.” Part of the regiment began to drift back into the cover of the trees. “No regiment could stand the fierce fire that poured in from front and flank,” observed a Wisconsin soldier watching from farther down the line. “It gave way.”102

With his regiment falling back through the trees, Colgrove tried desperately to halt his men. The dense brush and roar of battle, however, meant that no member of the regiment could see or hear more than ten of his comrades at a time. It was only upon reaching a small clearing about 150-200 yards back that Colgrove was able to rally and reform his men. His command “Forward!” was met with cheers. The colonel paused his regiment just before they returned to the fence line to allow the men to catch their breath and adjust the battle line. Then they plunged right back into the maelstrom.103

Annihilation or Retreat

Gordon’s small brigade could only hold back the Confederate tide for so long as darkness began to rapidly overtake the battlefield. The Confederate battle line had emerged from the trees into the wheatfield, where, in the words of a member of the Second Massachusetts, they were “received with a savage fire.” The Confederates, however, outnumbered Gordon’s men by several orders of magnitude and the same Massachusetts soldier grimly noted that the blue-clad “line is thinning fast.” From the perspective of a member of the newly-rallied Twenty-Seventh Indiana, the “enemy was pouring upon us such a deluge of missiles,” but, despite their numerical advantage, the Confederates ominously were not advancing to drive back the Federal line.104

Second Lieutenant Willian Van Arsdol was in his position several paces behind the rear rank of his Company A of the Twenty-Seventh Indiana when he happened to glance off to the right, past the flank of his regiment. To his horror, he spotted a heavy column of Confederate regiments advancing rapidly towards the Union rear. The junior officer shouted a warning to his men and ordered them to open fire on this new threat. He also sent urgent word to Colonel Colgrove, who galloped over to investigate.105

These gray-clad ranks belonged to the brigade commanded by Brigadier General William D. Pender, newly arrived on the field and moving up on the left flank of the Stonewall Brigade. Advancing in a column of companies along the western edge of the bushy field, the brigade suddenly wheeled each company simultaneously to the right to throw four full regiments against the flank of the Twenty-Seventh Indiana. By the time Colgrove rode up, Pender’s line was a mere 20 paces from the Union flank. Colgrove shouted for Van Arsdol’s Company A and the adjacent Company D to change their front to meet the Confederate onslaught.106